More Than James Brown’s Drummer: Clyde Stubblefield, An Unsung Pioneer of R&B

John Lingan on the Enduring Influence of One of the Genre's Most Iconic Drum Riffs

In the 1960s, R&B music was still designed to make you move. Hum any tune by one of the era’s many geniuses and stars and you’ll immediately think of its groove: “Green Onions,” with its hip-knocking blues; the finger-snap elegance of “My Girl”; Jackie Wilson’s lighter-than-air showmanship, epitomized by “(Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher.” Aretha’s “Respect,” Martha and the Vandellas’ “Heat Wave,” the Ronettes’ “Da Do Ron Ron”—an era when new and wonderful rhythms tumbled out of the radio constantly.

In successive weeks in August 1965, the Billboard R&B chart was topped by Wilson Pickett’s prototypical Southern-soul belter “In the Midnight Hour,” then by James Brown’s “I Got You (I Feel Good),” which is almost alien and stark in comparison, de-regionalized other than Brown’s unignorable Georgia drawl. It’s arguably the first appearance of a deviation into what became funk, then programmed dance music, then hip-hop and beyond.

But before all that, Brown’s next step was the one. Certainly, the Memphis titans Al Jackson and Howard Grimes knew how to hit their bass drum with authority. But Brown’s conception of the one was closer to an early New Orleans jazz musician’s. He built a feel, slamming down the first note of every bar before each band member spent the rest of the measure fanning out into syncopations, tight melody lines, and percussive stabs, and then careening back to the one again. It was an organizing principle, a philosophy, and it made Brown’s music relentless, like “Cold Sweat.”

Even though he got his moments onstage, Stubblefield finally couldn’t take “Brown” (his only term for his boss) anymore.

You could hear the influence of this change immediately, expressed by some of the era’s most significant talents. Sly Stone was an East Bay producer and stage musician for national touring acts, but when he founded Sly and the Family Stone in 1967 he established a unique, energizing sound built on catchy melodies atop Greg Errico’s deep-pocket drumming and Larry Graham’s popping bass. With their singsongy choruses and breezy melodies, “Everyday People” and “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” were like Saturday morning cartoon versions of James Brown funk songs.

Led Zeppelin broke out in 1969 playing psychedelic and souped-up blues, but by Led Zeppelin II later that year, especially “Whole Lotta Love,” they had started exploring repetitive, droning songs that hit the downbeat hard. (It took until 1973 for them to record an actual Brown tribute, “The Crunge.”) As the 1960s turned into the 1970s—literally, December 31, 1969—Jimi Hendrix debuted his new trio Band of Gypsys at Fillmore East, featuring the extravagantly Afroed singer-drummer Buddy Miles, who flashed both a passable croon and Stubblefield-style backbeat.

Even Miles Davis, Brown’s mirror image in so many ways, adopted rock and roll instrumentation at decade’s end. His first album-length steps in that direction, In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew, are rooted in a James Brown conception of rhythm rather than a Motown, Stax, or even Hendrix one. Davis was seeking an ultimate simplicity through grandiosity: huge overlapping bands playing twenty-minute songs with one chord.

Through the early 1970s, when he played rock venues like the Fillmores and DC’s Cellar Door, Davis pushed his band deeper into hard funk: backbeats, wah-wah guitars, minimalist bass. By 1972, when he released On the Corner and Brown released There It Is (featuring the peerless Jabo Starks strut “Talkin’ Loud and Saying Nothin’, Pt. 1”), the two men’s aesthetics were as close as they ever got.

In 1970, Brown’s band effectively threatened a labor strike in response to unfair working conditions. Brown infamously levied fines on his musicians for onstage mistakes, even insufficiently shined shoes, and he often took credit for their creative contributions. But he wasn’t going to be confronted by his underlings, and he responded to the threat by hiring replacement musicians from Cincinnati, including the Collins brothers, Bootsy and Catfish. These young guns combined with Clyde and Jabo to anchor a short-lived but essential band: the JB’s.

This is also where Fred Wesley entered the picture, and he recognized Stubblefield’s importance immediately. “Guitars were very important in that band,” he told me. “Jimmy Nolen and Catfish would play two different licks, then Clyde would add that steady beat. He could hold the same beat no matter how slow, how fast, loud, or soft.”

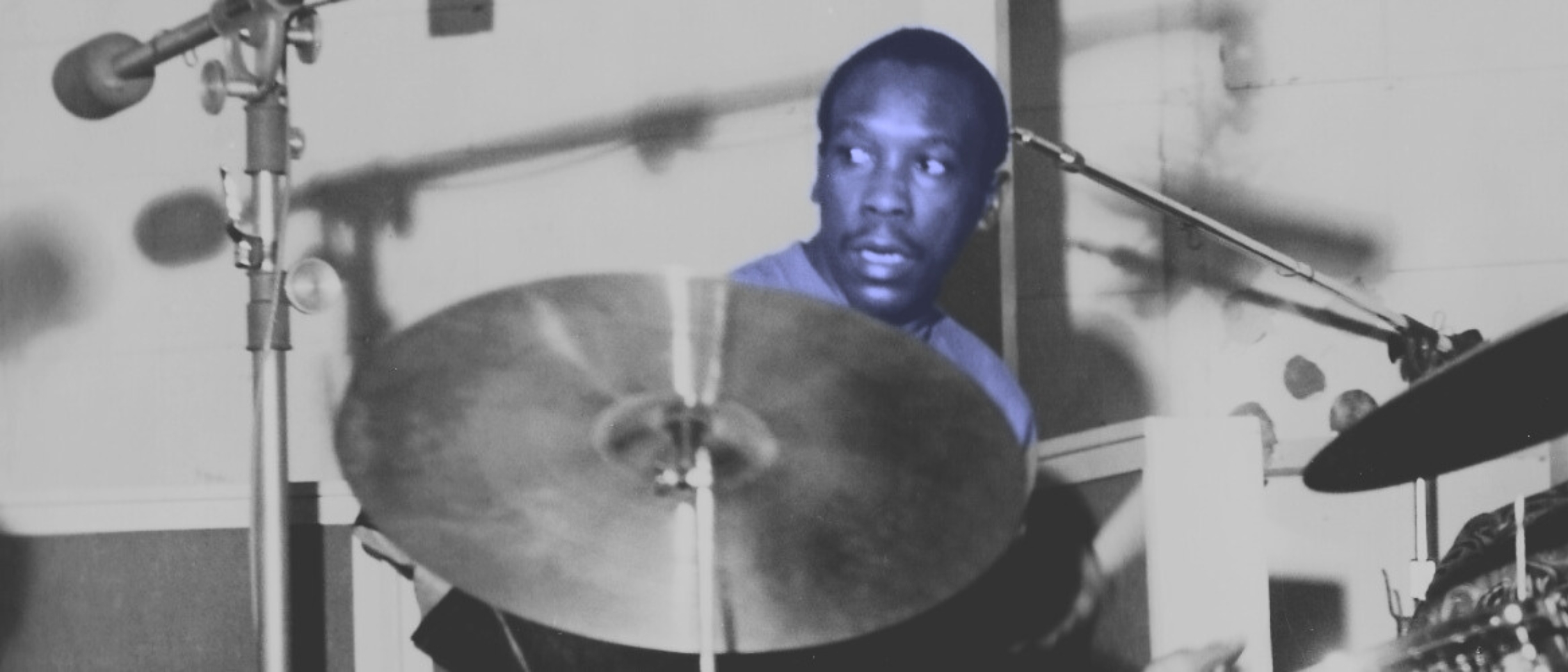

Nearly every note this band ever played together had an overwhelming power, but few illustrate Wesley’s description more perfectly than “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose,” specifically the “live” recording first released on the 1970 album Sex Machine, which includes overdubbed crowd noise. It’s a historically significant track, but I cannot remain a mere historian here; this “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose” is a fair nominee for my favorite drum performance of all time.

A simple Nolen guitar figure kicks things off, but this is unequivocally a drum feature, with congas in the mix for good measure. Stubblefield enters with the full band, sounding monumental: his bass drum is like a mammoth’s leg slamming to earth, his snare like Paul Bunyan’s axe. He kicks immediately into a beat that threads a needle between Bootsy’s walking bass line, and his ghost notes on the snare form a perfect double helix with the rolling congas. The song proceeds like this, occasionally breaking into a bridge but always returning to that one groove, with Catfish Collins’s distorted strumming on top of Nolen’s clean picking, just like Wesley said. And then around the time a commercial single would end, Brown cuts everyone out.

Just those congas remain, keeping basic time, while Brown keeps telling us, “Clap your hands, stomp your feet.” Over and over. Clap your hands. Stomp your feet. It feels like the fade-out could arrive at any time, until he finally says a single breathy syllable, as cool as any utterance by James Dean or Jean-Paul Belmondo: “Clyde.”

And at once, Stubblefield is back, and the band snaps to attention again, reassembling for another minute of work.

I’ve heard it hundreds of times, and that “Clyde” is still hair-raising. Literally and figuratively, Stubblefield is summoned. Brown gives him such prominence in this huge group, the music is in a holding pattern whenever he leaves. This performance is the funk “Sing Sing Sing.” Notably, DJ Kool Herc, a founding architect of hip-hop beat-making, created one of his earliest loops by switching between two turntables that were both playing this Stubblefield break.

But even though he got his moments onstage, Stubblefield finally couldn’t take “Brown” (his only term for his boss) anymore. He quit the group in 1971 while they were on tour, and for the next half century, as an increasing number of music obsessives approached in awe to ask him about those six years of his life, he was always happy to oblige and to take their compliments, but he never had a friendly word to say about his old employer, his onetime revolutionary leader.

*

In 1971, R&B drumming had been permanently marked by Clyde Stubblefield’s influence. The Meters, from New Orleans, were increasingly legendary for their deep, laid-back funk, and drummer Zigaboo Modeliste was another syncopation master. His interplay between snare and hi-hat, captured on their calling card “Cissy Strut,” from 1969, was like a half-speed Stubblefield groove turned inside out. The great James Gadson would soon be featured on Bill Withers’s second album, Still Bill, playing skittering patterns like the one on “Kissing My Love” that are unimaginable without the template of “Cold Sweat” or “Mother Popcorn.”

Session pros like Bernard “Pretty” Purdie and Steve Gadd kept their drums tuned tightly and peppered their snapping backbeats with ghost notes on their snares. As these men became well-paid industry royalty and other Brown-inspired groups like Funkadelic and the Ohio Players took root as well, Clyde Stubblefield settled down in the distinctly unfunky-seeming locale of Madison, Wisconsin.

Madison had a socially progressive community but was largely white and had fewer than two hundred thousand residents at the time. Somehow Stubblefield felt right at home. The first night he arrived he saw a jazz show by the local pianist Ben Sidran, who was beginning his own significant career.

“Within a few months we were recording together,” Sidran told me. Stubblefield handled drums on Sidran’s next record, even though the keyboardist says, “He was not a jazz player at all. He played straight eighth time, no swing. But his time was so good.” Electric funk-jazz was the mode of the day anyway, so Stubblefield fit right in. “Groove music was a big part of what my group did. We were playing a lot of extended dance stuff. And for me and the people I played with, James Brown in the sixties was like Miles or Coltrane. It was all one thing to us.”

Stubblefield’s place in Madison wasn’t limited to music. In this small northern city where he had no roots at all, he seemed at last to find his ultimate comfort—the exact opposite of life with Brown. “He watched cartoons, he liked to get high and hang out,” Sidran recalled of those days. “And he always had girls around. Clyde was really a force of nature. A big kid. Madison isn’t a racially diverse place but that never seemed to be an issue for him. There was no stigma around being a Black man for him. He was accepted for who he was, and he also wasn’t the first high-level Black musician who came through. Clyde never seemed to worry about money, being competitive, making it. There were many other bands who would have welcomed him but he loved Madison. The music scene was really healthy. It was inexpensive. He didn’t exhibit any desire to be famous. And he had no desire to talk about James Brown.”

Stubblefield became a close family friend of the Sidrans, something like a godfather to their son Leo, as well as the boy’s drum teacher. With such a different musical background, Ben Sidran was able to describe what made his friend such an effective drummer.

“His great contribution is placing the backbeat ahead or behind of where it would normally be. And then I saw up close, Clyde’s playing was so beautifully structured. He would think in eight-bar phrases. He would virtually compose in a song form. His playing was loud, so strong, but contained. Most drummers when they stretch, they get a little wild and crazy. But when his energy went up, the time stayed perfect, he could still lay back, he wouldn’t get out of control.”

Clyde Stubblefield, who created a bedrock part of late-twentieth-and-early-twenty-first-century pop culture on a whim during a nondescript session in 1969, never received a single residual for his troubles.

There Stubblefield was, playing neighborhood gigs in a midsize Midwestern city, growing into middle age, and perfectly content with his lot in life. He even trained Leo Sidran well enough that the boy could take over during gigs whenever Clyde wanted to smoke a joint outside. He didn’t spend too much time thinking of the money he should have been owed over the years, and as the ’70s turned over into the ’80s, even Brown struggled in an age of drum machines. Their collaborative heyday seemed like ages ago except to hard-core record collectors.

*

Then came the multiethnic, pan-cultural explosion of hip-hop, Specifically the culture of crate-digging and sample-based beat-making, where searching through old funk LPs for loopable grooves became its own form of artistry and amateur competition. And for any kid looking for beats to sample, those Brown-Stubblefield LPs and 45s were manna. Brown’s entire style presaged the idea of sampling; his music came pre-looped.

That “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose” drum break of course became a staple of this first era of hip-hop sampling. But of all things, an improvised studio jam from 1969, recorded in Cincinnati, became more popular than it ever was as an original single, “Funky Drummer.” This was a quiet, burbling groove that apparently impressed Brown, who decided once again, mid-recording, to give the drummer some. But he warned Stubblefield, “Don’t turn it loose, ’cause it’s a mother.” Don’t change the beat. So Stubblefield kept an uncharacteristically quiet groove going that rode a sixteenth-note pattern on the hi-hats, not Stubblefield’s typical big down- and backbeat.

That break’s use in “Erik B. Is President,” the 1986 debut single from Erik B. and Rakim, probably would have cemented its place in rap history. Then came “Mama Said Knock You Out,” “Fight the Power,” “Fuck tha Police,” and “Run’s House.” These were era-defining golden-age rap songs and “Funky Drummer” was the spine for all of them. That twenty-second drum break was like the “Johnny B. Goode” intro of the sampling age—a building block, a core sound, a stand-in for the entire attitude of the genre.

“Funky Drummer” made the leap into bubblegum (Kris Kross, Marky Mark, and Vanilla Ice all rapped over it) and into the greater pop world as well. Producers and artists have stretched, shifted, and repurposed this Stubblefield sample like nothing since Hal Blaine’s “Be My Baby” beat. It is simply part of the basic vocabulary of pop music now, after its use by Sinéad O’Connor, Prince, New Order, Nine Inch Nails, George Michael, Depeche Mode, the Beastie Boys, Nas—every conceivable realm of rhythm-oriented music. To my view, its very oddness as a Stubblefield track (the ticking hi-hats and underplayed bass and snare) made it infinitely adaptable. Producers could layer other sounds on it while retaining that perfect, indelible flow.

Depending on your familiarity with stories of other innovative Black musicians’ long-term economic fortunes, you may or not be surprised to hear that Clyde Stubblefield, who created a bedrock part of late-twentieth-and-early-twenty-first-century pop culture on a whim during a nondescript session in 1969, never received a single residual for his troubles. His old boss never credited him as a writer, not even on songs that were named for him, or that were largely sampled for his individual parts.

“People use my drum patterns on a lot of these songs,” he told The New York Times in 2011, in a piece about his efforts to pay for mounting medical bills. “They never gave me credit, never paid me. It didn’t bug me or disturb me, but I think it’s disrespectful not to pay people for what they use.” He saved his anger for the man who never game him songwriting credit in the first place. Fred Wesley told me frankly, “He would’ve rather starved to death than give homage to James Brown. He didn’t have a good word to say about him.”

Stubblefield lived until 2017, by all accounts a happy man with admirers and collaborators to spare and close friends in his longtime adopted home. By the time he passed, anyone who cared about the provenance of drum samples or the history of funk considered Clyde Stubblefield a god, as evidenced by the fact that Prince discreetly paid off the drummer’s entire $80,000 debt from cancer treatment. Modesty was deeply ingrained in him by then. When Prince died in 2016 and the news of his generosity finally came out, Stubblefield remained in awe of the gesture from a younger musician who called him his “drumming idol.”

“I still don’t understand why,” Stubblefield told Billboard.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Backbeats: A History of Rock and Roll in Fifteen Drummers by John Lingan. Copyright © 2025 Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.

John Lingan

John Lingan is the author of Backbeats: A History of Rock and Roll in Fifteen Drummers; Homeplace: A Southern Town, a Country Legend, and the Last Days of a Mountaintop Honky-Tonk; and A Song for Everyone: The Story of Creedence Clearwater Revival, named one of the Best Music Books of 2022 by Variety. He has written for The New York Times Magazine, The Washington Post, The Nation, and The Oxford American, among many other publications. He lives in Maryland.