More Dogs, More Dogs: Chloe Shaw in Conversation with Dinah Lenney

The Author of What Is a Dog? on the Books that Encouraged Her Creativity

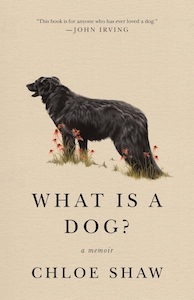

“For anyone who ever loved a dog,” says John Irving about Chloe Shaw’s debut. And that is certainly true—but I’d say What Is a Dog? is a book for anyone who ever loved anyone. Also for anyone who ever had to learn to love herself. Never was a story so human, I scribbled on the back of my galley when I got to the end. Never was a human so elegantly honest and vulnerable on the page, which doesn’t surprise me: not from a writer this lyrically gifted, thoughtful, self-aware. On top of which, dogs, if we let them, bring out the best in us humans; dogs, who love us unconditionally, who require so little in return—we don’t even need to be present for a dog, not as we do for the people who depend on us, and yet: if, like Shaw, we choose to be present, if we let a dog teach us to be present—with them, with the natural world, with ourselves—doesn’t that turn out to be a better way to live?

That’s one of the lessons of this book, but don’t mistake me. As insightful as she is, Chloe Shaw isn’t out to teach us anything. What is a Dog? is a personal reckoning with love, grief, family, friendship, and most especially self, in which the angle—the author’s way of getting to the truth about why, how, and who she is—is to track her relationships with dogs from childhood to the present; and most especially to examine the influence of Booker, the dog who came as part of a package deal (with her husband-to-be), and to whom she credits her coming of age as a lover, wife, mother, and writer, too. In other words, What Is a Dog? is a memoir.

The thing is, when I met Chloe nearly 20 years ago, we were students together in an MFA program. I was the one writing nonfiction—she was crafting stories and novels. So of course, I had to start by asking about that.

*

Dinah Lenney: Chloe, who knew, right? Was it strange to be writing nonfiction? Did you ever imagine you’d wind up with a memoir?

Chloe Shaw: To answer your second question first, no, never ever. But in the end, this feels like the book I’d always been meant to write—the book that perhaps I’ve been writing all of my life. Up until about three years ago, I’d almost exclusively been working on fiction. But in retrospect, I think I was hiding there. That’s not always a bad thing. Imagination can be a good friend in hard times, as it has been for me. But even in my fiction, I felt a bit trapped, like I couldn’t go all the way even in a world of my own making. I couldn’t let go. When Booker died, something inside of me cracked open. My voice, you might say. My heart. His death was the first death I was front-row-center for. I carried out all the vet visits, helped dig his grave, kissed him between the eyes when he was dead. This isn’t to say I haven’t lost anyone beloved (human and dog) before. But I’d always nimbly avoided that up-close role. It felt too hard. I feared I’d fall apart.

When I finally sat down to write about Booker, the language came so easily, like it had always been there. I was able to speak more honestly and to embody the words because suddenly—and finally—they felt like they were me. I was speaking from me as me. So, though I never expected to take this path, no, it didn’t feel strange. It felt exhilarating and relieving—and scary, of course. I recently read a quote from the writer and Family Secrets podcast host, Dani Shapiro, that describes literary memoir as: “an interrogation of one’s own memory in an attempt to make meaning and find the universal thread.” I love that description and think it beautifully describes what I went through in writing this memoir—the interrogation of memory and finding the universal thread, both processes of healing.

DL: “Speaking from me as me“—what a good description of the genre. But as easy as it was to write about Booker, the process you’re describing is anything but, right? Which parts of it were hard for you?

CS: There were two hard parts: the first time I heard the “M” word—for memoir (when I was asked to write the book)—and working through the middle, which is always hardest for me in any writing project. I love beginnings and endings. But finding your way from one to the other can be really tough. I try to remind myself of that great E.L. Doctorow quote that likens writing to driving at night. How you can only see as far as your headlights, but you can go the whole way like that.

DL: Daunting, but that’s the whole reason, right? Per Didion, to “write to find out what I think,” or per Hampl, to discover what we didn’t know we knew—

CS: Oh, a huge yes to the Didion quote! That was exactly my experience. What is a dog? is a pretty huge question—practically, spiritually, philosophically. Growing up, I was often too busy being the dog to consider what a dog is anyway. But as I wrote, I discovered I had quite a few thoughts and feelings on the topic. My canine companions weren’t simply my cute, fluffy counterparts, after all. There was so much to learn from them and from my relationships with them, so much reflection in their deep, sun-and-goop-filled eyes. Like Hampl, I feel I must have known these things all along, but never articulated any of it until I sat down to write.

When I finally sat down to write about Booker, the language came so easily, like it had always been there.

DL: Say more about the middle, though. Why was it hard? And what did you do when you got stuck?

CS: It was because I was both unraveling my memory in the book and in therapy. I felt like I was walking around for a good year with no skin on. But both the writing and the therapy, at least for me, always lead to a clearer place—sometimes sturdier, and always more present, accepting, and forgiving. I don’t know if I could have written this book without my simultaneous focus on my mental health. So I would say therapy certainly got me unstuck many times. So did hot showers. (I have a friend—Cyd—she took all those high-level math classes in college I couldn’t even tell you the names of, and she had a professor who used to assign “shower problems,” meaning you’d probably have to break for a hot shower just to figure them out.) And, of course, walking my dogs.

DL: And did you read about dogs? There’s a whole canon, isn’t there? Any recommendations?

CS: When I started writing my book, my editor had one rule: I wasn’t allowed to read dog books. A very good idea on his part, because if I had read A Three Dog Life by Abigail Thomas, I would have quit writing right there. It’s that good. I love Alexandra Horowitz’s Inside of a Dog, a more scientific take on how dogs perceive the world. Sing to It, stories by Amy Hempel. Unleashed by Jim Shepard and Amy Hempel, a collection of poems by writers in their dogs’ voices. The dogs of J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace will always stay with me. And I’ve always loved a James Herriot story, even when not about dogs.

DL: That was some smart advice (from your editor, I mean).

CS: Yes, I think it was so smart of him. There are so many dogs and so many types of dog books. It was necessary for me to go out and blindly find my own.

DL: So what did you read while you were writing? If not dog books, were you drawn to memoir at all? What are you reading now?

CS: I’ve been in an early-parenting, not-much-reading phase for a while now, but the same way Amy Hempel taught me to turn to poetry when I need a word boost while writing, and the same way I could only write short-shorts after 9/11, I’ve turned to shorter formats. I tend to read essays for that no-time-to-read reading boost. Might just be a few pages at a time, but sometimes that’s enough. I’ll pick up The New Yorker and read about food I haven’t eaten in so long, music I haven’t heard in so long, in my home city where I haven’t spent time in so long. And I’ll scour the New Haven Independent for my local versions of those things.

I’ve also been reading cookbooks. Sometimes just to savor the recipes, sometimes to mentally prepare to make a grown-up, stand-out meal one of these days. And, also, still, always poetry. My brother-in-law just shared Delmore Schwartz’s “Dogs Are Shakespearean, Children Are Strangers” with me and it was exactly what I needed. But right now I’m reading Jim Shepard’s latest novel Phase Six. He wrote it pre-pandemic and it’s about… the next pandemic. You might think you don’t want to read about that topic right now, but as with all of his work, every sentence is a marvel of precision, language, and heart. It’s astonishing.

As to memoir, I’ve always been drawn to real stories from real people—perhaps even more than fiction even while I was rabidly writing fiction. So maybe this is one of those things, about myself, I didn’t know I knew? At least for now, the real world, as magnificent and horrid as it can be, is where I’m most comfortable.

DL: Well, you’ve written both (the magnificent and the horrid) with what feels like genuine compassion and lightness and love. Speaking of which, this book is as much about your people as your dogs. (You could have titled it What Is a Family?) I wonder how they feel about that—

CS: On the topic of writing about family, Shepard, who was my mentor in college, told me my favorite thing: “Well, you can just not do it, hope they don’t read it, or wait until they’re dead.” My parents, my husband, and my kids are luckily still very alive and kicking, so that was a big challenge for me at first. What helped me most was knowing that the book was always meant to be a personal meditation on dogs. With each draft—I think six in total—my editor kept saying, “More dogs, more dogs.” So that took a little pressure off. My family experiences certainly informed the writing, but in draft after draft I realized there were pieces that took me too far from my subject—they just didn’t belong in this book. Where I finally landed feels like the right balance to me: true to the worlds of each stage of my life, but always focused on the dogs.

DL: I want to go back to what you said earlier about writing and therapy coinciding with this project. Do you remember which came first? I once heard a writer say that therapy doesn’t always lead to good writing, but good writing is almost always therapeutic. Does that ring true for you?

The real world, as magnificent and horrid as it can be, is where I’m most comfortable.

CS: Well, dogs came first, then writing, then therapy. I’d say they all go hand-in-hand for me in terms of what has helped me live this life in different ways. Dogs absorb you. While we hide our broken hearts in shame, a dog becomes the broken heart. Writing, on the other hand (for me, at least), until now anyway, has been an escape, a release of me from me. I agree that therapy doesn’t always lead to good writing, but for me it’s always helped me at least get to a better place from which to write. Certainly, with this book that was true. And I definitely agree that good writing is always therapeutic.

DL: And your husband is himself a therapist, right? He’s such a strong presence in this book. Quiet but bolstering. Does that make him a good reader for you?

CS: He’s my first reader, always. As a psychoanalyst (and a very smart reader) he brings a whole different set of very important eyes. It was trickier with this book since it’s not only nonfiction, it’s memoir, meaning he’s in there, too. But he braved it anyway.

DL: Did he help you to kill your darlings? Talk about that—about the parts you had to leave out.

CS: There are so many! I’m a word/sentence writer and reader. I could write sentences for days and not care if they add up to a whole. I could read about anything as long as the language stops me in my tracks. So there are sentences that were very, very hard to kill, Darling. Those stay with me more than any anecdotes or scenes. There are a few sentences toward the end that are some of my favorite sentences in the book. Even though she loved them, too, one of my editors wanted me to take them out because of pacing. I took one or two out then made a couple of adjustments and convinced her the rest needed to stay. It felt good to know you don’t always have to kill your darlings. Sometimes you just need to adjust and fight for them. In the end, I couldn’t be happier with what made the cut—and what didn’t.

DL: So do you think you’ll keep writing memoir? Do you have any desire to go back to fiction? (I guess I’m asking what’s next—)

CS: I have been thinking about this so much. An honest answer is, I’m not sure. There is no question that writing nonfiction allowed me to break out of myself, to break out of my fear of vulnerability and truth. And that feels so good. Better than any fiction has ever made me feel. Even though I have one old and one new fiction project (mostly just in concept at this point) in my orbit, I told my husband the other night that I’m not sure I can go back to fiction now that I’ve written this book. He said, “But what if all of this makes your fiction even better?” You can see why he’s my first reader.

__________________________________

What Is a Dog? is available from Flatiron Books. Copyright © 2021 by Chloe Shaw.

Dinah Lenney

Dinah Lenney is the author or editor of five books, including The Object Parade, Bigger than Life: A Murder, a Memoir, and, most recently Coffee, part of Bloomsbury's Object Lessons series. An editor-at-large for the Los Angeles Review of Books, she teaches nonfiction in the Bennington Writing Seminars.