Money, Priorities, and the Promise of an American Childhood

Qian Julie Wang on the Summer of 1998

The summer of 1998 marked the most acquisitive time of my American childhood. At graduation, my dream had come true: I had won an award from the local Lions Club that came with a $50 gift certificate to Barnes & Noble, a store I revered so much I rarely dared to enter its doors. After the ceremony, I had walked to the East Broadway subway station between Ma Ma and Ba Ba in a daze, pinching the gift certificate between clammy fingers, rings of wetness developing on the paper. Even so, I couldn’t bring myself to stow it away in a folder in my backpack, as Ba Ba had urged. If I stopped holding it, I would cease to believe it was real, for I had never dreamed that I would one day have so much to spend at an actual bookstore.

The following Sunday, Ba Ba took me to Barnes & Noble. The green awnings and gold letters stood on the chest of the multilevel store that beamed with pride over the trees of Union Square. For the next two hours, we made our way through the store, I poring over the tides on the shelves as Ba Ba looked on through sleepy eyes. At the end of each floor, we took the escalator up to the next level, my arms loading up with far more prospective purchases than I could afford.

We settled down in the kids’ section and surveyed my choices. The decision weighed on me, drooping my shoulders. On the one hand (quite literally), I had several Baby-Sitters Club books that I had for years longed to own for myself. Their covers were shiny and smooth; their pages still rested tightly together, unmarked by the intrusion of strangers’ fingers. On the other hand, I had books of duty that Ba Ba commended to me: a textbook with a tree on the cover, overlaid with the words What Your 6th Grader Needs to Know, and a hardcover Merriam-Webster dictionary that I had only ever seen on a special wooden stand at the library. The dictionary was so large that my arm had started to shake under its weight.

“Qian Qian”—at the tone of Ba Ba’s voice, I knew his mind was made up—”you know you can come here and read those babysitter books anytime:’

“I can?”

“Yes. This is just like the library, except you can’t take the books home for free.”

I looked around and took in for the first time the little white boys and girls, sitting on stools, on the floor, and on their parents’ laps, flipping through pages with all the time in the world.

As I carried my purchases out, I noted that the bulging green bags brought me no happiness. Instead, I felt heavy. Somber.

“I didn’t know. I thought they would kick me out. But I have fifty dollars—shouldn’t I use it?”

“Of course. But use it on something you can’t read here. Some thing you need to have at home.” He pointed to the books of duty.

I hesitated. The covers did not excite me. They did not comfort me. They made me sleepy.

“You can learn big words, so they’ll never know that you’re an immigrant. Look”—he grabbed the dictionary with indentations along the side for each letter of the alphabet, and flipped to a section just before the C indentation—”you can look up a word like bird, and here’s a section showing you what it means.”

“But I already know what bird means.”

“Oh, but think of everything you don’t know! They’re all here, Qian Qian. The whole world is here, between these covers.”

I liked the sound of that. Most of all, I liked that I could help Ba Ba believe that one day, no one would think we were immigrants, that we really and truly belonged here.

Wo zai zhe li sheng de. Wo yi zhi jiu zai Mei Guo. I was born here. I’ve always lived in America .

“And, you see?” He knocked his fist against the cover. “It’s great quality. It will last you until college.”

I thought back to what Ma Ma had said before she got sick, that there were certain colleges that didn’t ask too many questions, if l was good enough to get in. I could not spare a single effort. That solved the dilemma: I bought the dictionary and spent the remaining amount on the textbook, vowing to work through each of them every day. I left the Baby-Sitters Club books in a neat pile by our chairs. Perhaps I could come back to visit them. Or they might bring joy to someone else.

I walked away from the cashier hand in hand with Ba Ba, proud to give him hope. I would study five words a day every day, I told him, and within a year I would know all the words in the world.

He smiled and it was all I could do to reflect his joy.

But as I carried my purchases out, I noted that the bulging green bags brought me no happiness. Instead, I felt heavy. Somber. At least, I reminded myself, I was $50 closer to attending college.

I never did touch those books again. For the rest of our days in America, they sat by my bed, a reminder of Ba Ba’s waning dreams for me.

*

My second big acquisition came later in the summer, when the Brooklyn heat had us passing time on the front steps after dinner, enjoying the breeze that fanned the setting sun. Ba Ba came home through that heat one evening in a soaked-through white shirt and pride on his face. Before changing out of his clothes, he presented me with a box in a stiff, translucent plastic bag.

Hope dashed through my chest over what it might be. For the entire school year, I had lusted after my classmates’ Tamagotchis, little egg-shaped electronic toys in varying colors, each housing a digital chick that needed to be fed and played with, like Marilyn. Over the fourth-grade summer and into the start of fifth grade, all of my friends got one. I had showed up to class one morning to find that I was the only one who did not have a beeping, needy pet in her palm. Some of my classmates even had three, each in a different color. I would spend most of my classes looking over my friends’ shoulders at their pet chicks—a constellation of black pixels, really—and all that they demanded. They needed to be fed, cleaned, played with, and disciplined, all within hours. If they were ignored, they died, something that once happened to Hanna Lee twice in one day.

The whole idea seemed stressful and not particularly fun, but everyone had one, so of course I wanted one. I had spent most of my fifth grade year walking around with my eyes fixed on the ground, convinced that I would find one dropped by a careless kid. I pictured myself picking the egg out from between a grate, dusting it off, and giving the chick a clean, loving home full of games and food and discipline. Whenever a friend let me hold her Tamagotchi, I imagined running off with the chick and living together in happiness until I raised him into a full-grown rooster, with a pixelated comb and all.

Now, time slowed as I retrieved the box from the bag Ba Ba handed me, and quickened again as soon as I saw what it was. The box was rectangular, white on the sides. The front was clear, and in its center was a flattened, oval white egg with a keychain attached. The white shell was cracked in the center, exposing a screen edged in blue. At the bottom, three blue buttons protruded. I looked up at Ba Ba.

“Did I get the right one? I asked for the egg with a chicken in it.” A few months before, Ba Ba had scolded me for not checking both ways while crossing the street. I had been too busy searching the ground for a homeless Tamagotchi in need of adoption. I told Ba Ba what I was looking for, going into lengthy detail as to what the game looked like and how it worked. Ba Ba responded only, “Look where you’re going, Xi Mou Hou. You’re not going to get your chicken that way.”

I forgot the conversation as soon as it was over, returning to scouring the streets with my eyes. It never occurred to me that we might be able to somehow afford a brand-new Tamagotchi, and even then, it wouldn’t have felt right to buy a baby chick instead of more healthy food for Ma Ma. Plus, I had had many other similar, unrequited obsessions in America: the full-size Barbie doll, the Furby, and the G-Shock Baby-G watch. None of them ever came to fruition, and they all petered off into a whispered longing.

But with the Tamagotchi, it was different. I finally had one. I wrapped Ba Ba in a great big hug, he bending down in his sweaty shirt, I reaching up on the tips of my toes. Then I ripped open the box and yanked the plastic tag out of the egg, hurling myself onto the couch as my chick beeped into life, leaving Ba Ba free to unburden himself of his sodden clothes.

*

It was, in fact, an acquisitive summer for all of us. After the Tamagotchi, and just before I was to start at Lab, Ba Ba came home with yet another surprise.

Ma Ma had come home first that day, and she was already in the kitchen steaming the vegetables we had ferried from Chinatown earlier that week: onions, carrots, and cabbage. We took care to go toward the end of the day, when vendors were eager to dispose of what had baked for long hours in the mixture of summer sun and car exhaust. Sometimes, when we went late enough, we even got sweet potatoes on steep discount.

I started to laugh at first, so impossible was the idea of us owning a car.

Meanwhile, I was splayed out on our new forest-green couch, playing with my little chick. The couch was a new find from a recent shopping day. It was stiff and uncomfortable but looked much cleaner than our old one. Earlier that week, as we dragged that old couch out through the doors and onto the front steps, I looked at the embracing cushions, slouchy and soft from the years of sitting we shared, and asked Ma Ma why we had to get rid of a reliable, comfortable couch for an unknown hard one. Ma Ma explained that the look of things sometimes meant more than how they felt. The green couch looked newer, cleaner, more expensive. It would inspire us to work harder. It might even bring us good luck and prosperity. The toughness of the polyester bumps under me flowed in and out of my mind as I got my chick up to full health. I had developed a habit of doing that whenever I could, because I never knew what was to come the next day, and how long it might be before I could get back to my chick. It was better to load her up early. Like with Marilyn.

Then Ba Ba burst into the room, startling me into a seated position. “Come, come! Hurry!” By the time I left my chick and walked out of the room, he had already run down the hall to the kitchen, from which he was leading Ma Ma out by the hand. I could not remember the last time I had seen Ba Ba holding Ma Ma’s hand, so I figured that the news must be big, important. Ba Ba had left the front doors open, which he never did, and he waved all three of us through. He pointed at a car parked just outside our door. It was a four-door sedan that reminded me of a long, flat shoe, and it had the same shimmery gold color of the scratched-off shavings from the Bingo cards.

“There’s always a car parked here, Ba Ba.” I was eager to return to my chick; I was so close to getting her health to perfect.

“The stove is on—I should get back.” Ma Ma did not seem impressed, either.

“No, no,” and with this, Ba Ba ran down the steps and opened a door of the car. “This car is ours.”

I started to laugh at first, so impossible was the idea of us owning a car. Money aside, Ma Ma didn’t even have a driver’s license. Ba Ba had been learning with Lao Jim and had only recently gotten his. I still could not believe that Ba Ba had been willing to walk into a government office. Wasn’t he worried that they would arrest and deport him? Lao Bai had told him that he was able to get his license with no trouble, but how did Ba Ba know for sure that it would be safe? Wasn’t he worried that it was a trick?

In the end, he said, he just wanted a taste of what it was like to be a real American.

Ma Ma and I remained silent for so long that Ba Ba launched into a series of explanations: there had been a really good deal, a once-in-a-lifetime offer; he had to accept it in the moment or else; we still had some money left in that brown suitcase—we just had to save a little more later this year to get our savings back; there had been no time to check with Ma Ma before he made the decision; with the car, we could get to places, buy food for less, and maybe even move to another state where everything was cheaper and there would be more opportunities for Ma Ma and her degree. I bobbed my head from Ba Ba to Ma Ma and back as Ba Ba engaged in his plea. But it was too late: there was a storm on Ma Ma’s face.

“I have to check on the stove.”

As Ma Ma walked back into the house, I watched Ba Ba stare at his feet. He looked up again and offered me a smile. “What do you say, Xi Mou Hou-want to go for a drive?”

I didn’t understand what had happened, but I did know that Ba Ba had done something bad. I very much wanted to know what it was like to own a car. I wondered whether the ceiling also drooped. And I wondered whether, like Lao Jim’s car, it smelled like old man and garlic, whether it also shuddered before coming to a stop. Most of all, I wondered what it would be like to drive down any street we liked—not just the streets that led to McDonald’s. What was it like to slow down or speed up at our will? What was it like to have the cool air roll through the lowered windows and kiss my cheeks as Ba Ba and I navigated through our neighborhood, just the two of us me in the front seat for once!—chitchatting about starting middle school like I was any other normal American kid?

But instead of finding out, I shook my head. Ma Ma was mad at Ba Ba about the car, so I would be mad at Ba Ba about the car.

“I don’t want to miss dinner,” I said.

Just as I turned to walk back toward my little chick, I caught the sight of Ba Ba standing alone by his new car, face dark with the sadness of a boy who had no one to play with.

*

We ate dinner in the simmer of contempt that night. Although we sat in the same spots around the same table as we always did, Ma Ma and Ba Ba were now farther away from each other. I wished for them to scold me and yell at me, about my lack of discipline, my teeth, my sloppiness, my anything. But they exchanged no looks or words, staring only at the plates of steamed onions, carrots, cabbage, and bland, boiled chicken. The meal concluded when Ba Ba got up. He placed his plate and chopsticks in the sink before cleaning the large bowl that Ma Ma had used to rinse the cabbage. He then filled it with water and grabbed our dish towel before walking out of the kitchen and down the hallway. Ma Ma and I sat staring at the table as we heard him open the front door and then slam it shut. He stayed out for almost an hour, and I knew only from looking through the sunroom windows later that he was washing the car by hand, with tender care that I forgot he possessed.

After Ba Ba stepped out, Ma Ma got up and began placing the leftovers into the fridge, gathering in the sink the dirty plates and bowls. I walked over to the sink and began my nightly dishwashing. To our roommates, it must have looked like just another night.

__________________________________

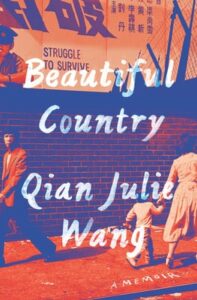

From Beautiful Country: A Memoir by Qian Julie Wang, published by Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Qian Julie Wang

Qian Julie Wang

Qian Julie Wang is a graduate of Yale Law School and Swarthmore College. Formerly a commercial litigator, she is now managing partner of Gottlieb & Wang LLP, a firm dedicated to advocating for education and civil rights. Her writing has appeared in major publications such as the New York Times and the Washington Post. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband and their two rescue dogs, Salty and Peppers.