The big glass pyramid amused Mona. Brazenly hoisted in the middle of the stone edifice of the Louvre Palace, its ethereal form, its transparence, the way it caught the cold November sunlight, enchanted her. Her grandfather wasn’t saying much. And yet she could tell he was in a great mood because he was gripping her little hand in his with the confident affection of happy people, and blithely swinging his arms. Although silent, he was the picture of childlike joviality.

“How beautiful the pyramid is, Dadé! Looks like a giant Chinese hat,” Mona enthused, while cleaving her way through the clusters of tourists on the forecourt.

Henry looked at her and smiled, but with a kind of dubious pout. The odd look this gave him made the little girl giggle. They entered the glass structure, passed through security, glided down on an escalator, found themselves in the vast hall, so similar to those of stations and airports, and headed for the Denon Wing. All the commotion around them was stifling. Yes, stifling, because most visitors in the crowds at a large museum don’t know what they want to do; they foment a generalized indecision, making the atmosphere stagnant, uncertain, and even a bit uneasy, typical of such places when they are victims of their own success.

In the midst of the hubbub, Henry bent his long, thin legs to speak to his granddaughter eye to eye. He would do this whenever he had something really important to say to her. His mineral voice, clear and deep, drowned out the surrounding din. As if reducing to silence the inane chatter and tedious outbursts of the entire universe.

“Mona, every week, we’ll go to the museum together to see a work of art—a single work of art, only one. These people around us want to gobble it all up in one go, and they get lost, not knowing how to moderate their desires. We’ll be much wiser, much more reasonable. We’ll look at a single work of art, first without saying a word, for a good few minutes, and then we’ll talk about it.”

“Really? I thought we’d be going to see the doctor.” She wanted to say “the psychiatrist,” but wasn’t quite sure of the word.

“Tell me, Mona, would you like to go see the psychiatrist, afterwards? Is it important to you?”

“Anything would be better than that!”

“Well then, listen carefully, my dear. There’ll be no need to go if you really look at what we’re going to see.”

“Seriously? Can we avoid,” she stumbled again over the word, so decided upon a simpler one. “The doctor?”

“We can. I swear to you, on all that’s beautiful on earth.”

*

After tackling a maze of stairways, Henry and Mona found themselves in a bustling, crowded, modest-sized room. Almost nobody seemed interested in taking a good look at the work in pride of place as they filed past. Henry released his granddaughter’s hand and told her, with infinite gentleness:

“Now look, Mona. Take all the time you need to look, to really look.”

And so Mona, feeling a bit intimidated, planted herself in front of the painting. It was damaged, severely cracked in several places, and missing some pieces. Initially, it seemed to evoke a decayed and distant past. Henry gazed at it, too, but more than anything he was observing his granddaughter, sensing her uncertainty, her puzzlement. And then she was frowning and stifling a slightly embarrassed laugh. He knew that even when standing in front of a Renaissance masterpiece, a little girl of ten, no matter how vivacious, curious, sensitive and smart she might be, couldn’t instantly go into ecstasy. He knew that, contrary to a received notion, it took time, that plumbing the depths of art was a tedious exercise, not an easy delight. He also knew that Mona, because it was him asking her to, would play the game and, despite her awkwardness, would examine, with the promised attention, the forms, the colors, the subject matter.

*

The image was divided simply. To the far left, you could see a fountain, in front of which, like in a frieze, stood four young women with long curly hair, looking remarkably similar. They were gripping each other’s arms, entwined as if forming a human garland, which was punctuated by the difference in their outfits: green and mauve for the first, white for the second, pink for the third, orangey yellow for the fourth. This colorful procession gave an impression of forward movement, and facing it, on the right side of the work, alone against a neutral backdrop, stood a fifth woman, young, extremely beautiful, wearing an exquisite pendant-necklace and a crimson dress. She, too, seemed to be moving forward, as if to meet the procession. Indeed, she was holding a piece of linen out towards it, into which one of the creatures—the one in pink—was delicately placing something. But what? Impossible to say. The object had faded away. There was also, in the foreground, in the right-hand corner, a little blond-haired boy, in profile, almost smiling. The setting was almost entirely bare: only a blurred truncated column on the far right echoed the fountain on the far left.

*

Mona did play the game. But six minutes was already too long. Six minutes in front of a faded image was an unfamiliar and painful ordeal. So she turned to her grandfather and started the conversation with a cheek only she could get away with:

“Dadé, your painting’s really battered! Next to it, your face seems brand new.”

Henry looked at the work and all the damage scarring it. He crouched down.

“You’d be better off listening to me rather than talking nonsense . . . A ‘painting,’ you say! Wrong! For a start, Mona, it isn’t a ‘painting.’ It’s what’s known as a ‘fresco.’ Do you know what a fresco is?”

“Yes, I think so . . . but I’ve forgotten!”

“A fresco is a painting done on a wall, and it’s very fragile because if the wall gets damaged—and a wall crumbles away a lot, over time—well, the painting gets damaged, too.”

“Why did the artist paint on this wall? Because it’s the Louvre?”

“Not at all. It’s true that an artist might want to paint a fresco in the Louvre, because it’s the biggest museum on the planet, and a painter would naturally want to place his work directly onto it, so it would be like the skin of the palace. But you see, Mona, the Louvre hasn’t always been a museum. Until about two hundred years ago, it was a castle, where the kings and their courts lived. This fresco was painted around 1485. So, the artist didn’t create it for the walls of the Louvre, but for those of a villa in Florence.”

“Florence?!” She fiddled, automatically, with the pendant around her neck. “That reminds me of the name of an old fiancée of yours, before Mamie, right?”

“Doesn’t ring a bell, but it’s possible! But listen; Florence is an Italian city. In Tuscany, to be precise. And it was the cradle of what’s called the Italian Renaissance. In the 15th century—the Quattrocento, as the Italians say—Florence was really flourishing. It had around a hundred thousand inhabitants and the city was prosperous, thanks to commerce and banking. Religious orders, political dignitaries, and even ordinary citizens, those at the top of the social ladder, wanted to make the most of their wealth and show their prestige by supporting the art of their contemporaries. They’re described as having been great patrons of the arts. Painters, sculptors, architects benefited from their faith and the means they gave them to produce some incredibly beautiful paintings, statues or buildings.”

“I bet they were made of gold.”

“Not entirely. There were, indeed, in the Middle Ages, some very fine paintings covered in lashings of gold leaf. It added value to the object, and symbolized divine light, to boot! But during the Renaissance, painting moves progressively from gilded showiness to a more faithful depiction of reality as we see it, with its landscapes, the singularity of faces, animals, the movement of beings, of things, of the sky and of the sea.”

“They love nature, is that it?”

“Precisely, they start to love nature. But you know when we talk of nature, we’re not only talking about what grows on the earth.”

“What do you mean?”

“We’re also talking, in a more general way, about human nature. That is, what we are deep down, with our dark and light sides, our flaws and qualities, our fears and hopes. It’s this very human nature that the artist seeks to improve.”

“How?”

“If you cultivate your garden, you do good to nature. You allow it to flourish. This fresco seeks to do good to human nature by telling it something very simple, but essential, and which you must remember forever, Mona.”

But Mona, to ruffle the old man, put her fingers in her ears and closed her eyes, as if she didn’t want to hear or see anything he might tell or show her. After a few seconds, she sneakily half-opened one eye to see his reaction. He was smiling, nonchalantly. So she stopped her little game and refocused all her attention. Because she sensed that, after those long minutes of silence, contemplation and discussion, after that little journey across the damaged picture before her eyes, her grandfather was finally going to reveal to her one of those secrets you keep very close to your heart.

Henry indicated to her to look at the slightly faded area, where there seemed to be something that the young woman on the right was taking into her hands. The little girl did just that.

“The four women in procession on the left are Venus and the Three Graces. They are generous divinities. And they are presenting a gift—we don’t know what it is because there’s a little paint missing—to a young girl. The Three Graces are what are known as allegories, Mona: they don’t exist in real life and you’ll never encounter them, but they represent important values. They are said to represent the three stages that make us sociable and hospitable beings, that’s to say, humans who are truly human. And this fresco depicts how essential these three stages are; it seeks to anchor them firmly in each one of us.”

“What are the three stages?”

“The first consists of knowing how to give, the third of knowing how to give back. And between the two, there’s one without which nothing is possible, that’s like a kind of keystone, one which supports all of human nature.”

“Which one’s that, Dadé?”

“Look: what’s she doing, the young girl on the right?”

“You told me: she’s lucky because she’s receiving a present.”

“Exactly, Mona. She’s receiving a present. And it’s that that is absolutely fundamental. Knowing how to receive. What this fresco is saying is that we have to learn to receive, that human nature, to be capable of great and beautiful things, must be ready to embrace the kindness of others, their desire to give pleasure, to embrace what it doesn’t yet have, and what it isn’t yet. There’ll always be time for the person receiving to give back, but to give back, that’s to say, give again, it’s crucial to have been capable of receiving. Do you understand, Mona?”

“It’s a bit complicated, your story, but yes, I think so.”

“I’m sure you understand! And you see, if these ladies are so beautiful, drawn with such fluidity and grace, this unbroken line showing not a jolt, not a doubt, it’s to express the importance of this continuity, of this chain that links humans and improves their nature: giving, receiving, and giving back; giving, receiving, and giving back; giving, receiving, and giving back.”

Mona didn’t know what to say anymore. The last thing she wanted to do was disappoint her grandfather. She’d already tried humor during their conversation, so she kept quiet to avoid adding anything too naïve, knowing very well that he was talking to her and bringing her to this huge museum so she became a bit more grown up. For now, she felt just a wrench, because this call to grow up, this thrilling exploration of a new world, exerted an extraordinary magnetic pull, particularly because the call came from Henry, whom she revered. And yet, she had an awful presentiment, a fear in her soul that what you give back, you might never find again. Regret, distant as it was vivid, for a forever vanished childhood clamped on her heart.

“Shall we go, Dadé? Head back?”

“Yes, Mona! Let’s head back!”

Henry took her hand again and they left the Louvre slowly, without a word. Outside, darkness was starting to fall. Henry was aware of the turmoil that had just shaken his granddaughter. But he refused to go easy on people just to ensure he had only good times, that were fulfilling and appealing, in their company. No: he knew very well that life is only worthwhile if you accept its harsh sides, and that these, once time has done its job, turn out to be precious and fertile material, beautiful and useful, that allows life to be truly life.

Besides, by that miracle that is childhood, Mona’s turmoil was short-lived: as she skipped merrily along, she started to sing. Henry never interrupted her at such times, which he found unbelievably touching. And then suddenly, as they were nearing her home, Mona stopped, having remembered the shared lie they’d agreed on to avoid sessions with the psychiatrist. She widened her big blue eyes and turned up her mischievous little face, chuckling at the naughty trick they were playing on her parents.

“Dadé, what do I say if Mommy and Daddy ask me the name of the doctor I went to see?”

“Tell them he’s called Dr. Botticelli.”

__________________________________

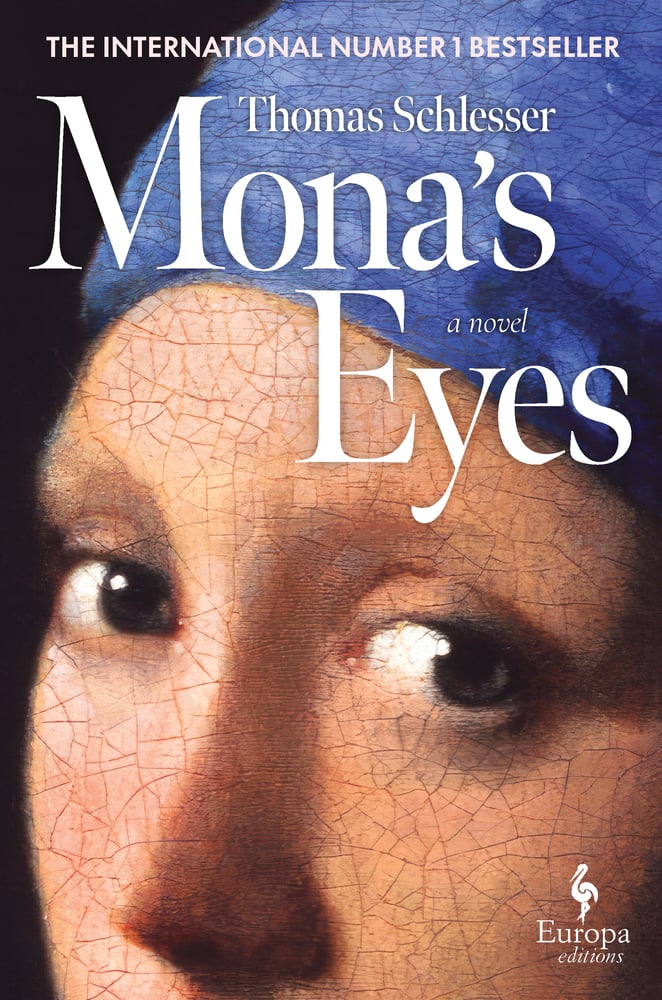

Excerpted from Mona’s Eyes by Thomas Schlesser, with permission from Europa Editions, 2025, www.europaeditions.com.