Girlie was, by every conceivable metric, one of the very best. All the chaff, long ago burned up by unquenchable fire: the ones who had hourly panic attacks, the ones who took up drinking; the ones who fucked in the stairwells during break time, the ones who started bringing handguns to the office, the ones who started believing the Holocaust had never happened, or that 9/11 was an inside job, or that no one had ever been to the moon at all, or that every presidential candidate was picked by a cosmic society of devils who communicated across interplanetary channels; the ones who took the work home, the ones who never came back the same, or never came back at all. The floor was now averaging only three or four suicide attempts a year, down from one or two a month. The ones who remained, like her, were the wheat: the exemplars, tested paladins, the ones who didn’t throw up in the hallway and leave the vomit there. They’d been, to continue speaking of it biblically, separated.

None of the white people survived. Not that there were that many of them to begin with. Young middle‑class hopefuls bulging with student debt, they’d shown up around the time the position was still being called process executive, back when the site was still in the Bay Area. Back when she still lived in the Bay Area; back when any of them still could. Most of the white candidates didn’t make it past the initial three‑week training course; the ones who did left within a year. The majority of the workers had been Filipinas, with a smaller minority of Cambodian, Indonesian, Laotian, Vietnamese workers: people who knew about the job through that reliable network still unmatched by LinkedIn, otherwise known as family—people who’d grown up knowing their mothers and aunts had been moderators, and so too would they follow. Sometimes a particular year—she’d started to think of her surviving cohort as a kind of graduating class, although what they were graduating from or toward, she did not know—would have one or two working‑class Korean Americans, one or two Black Americans, usually people who were married to Filipina or Viet employees and had heard about the job through them. Of the two hundred or so who worked at the Vegas site, nearly all were women. Nearly all the women were Pinay.

To pass her final assessment, Girlie’d had to stand in a conference room of no great nor small size, indistinguishable from the nine other conference rooms in the building, and, in front of her peers and potential future colleagues, moderate a video of a tied‑up and blindfolded young girl of about six or seven who was being made to fellate an unseen man. The girl had bruises along her shoulders. The man, who was recording and audibly enjoying the act, had gray in his pubic hair. The trainees had already been reminded that they wouldn’t be allowed to pause the video or remove the audio during their presentation.

Earlier that morning, a young Cambodian American trainee who wore three soft friendship bracelets around his left wrist—two fraying, one new—had moderated a video of a young man, about the same age as himself, being stabbed multiple times, gurgling bright blood into a Champion sweatshirt as he abortively begged for something; not quite yet his life. In the middle of his presentation, the young trainee, without pausing the video, discreetly crouched behind his podium to throw up into a wastepaper bin he’d presumably positioned there for this very reason. By the time it was Girlie’s turn, the room still smelled of pepperoni and bile.

Girlie stood in front of her prospective coworkers and managers, presenting a carefully supported case for why the video of the tied‑up girl should be banned from the social media site in question, on the grounds of child pornography. On the one‑to‑five scale they’d all been taught, the video was a solid five.

One of her potential supervisors challenged her, face stony: How did she know the girl was a child, and not a consenting adult?

It was true, they could barely make out the girl’s face, behind the blindfold, on the blurry blown‑up image beamed on the matte‑white projector screen, in front of the forty faces waiting, as in a court of law, for a verdict. It was true, there were plenty of small‑breasted, small‑boned women in the world, Girlie among them; it was true, there were plenty of people who cried during sex, or liked rough play of all descriptions. This was the real test of the moderator, in the end: being able to sift through, again and again, each workday’s thousand and one true things. This was the real work, beyond the stabbings, the rapes, the paranoia, the conspiracy theories, the hate speech, the carved‑out crater in the living world where belief had collapsed in on itself like an exploding star. Reaching into the wound with two clean fingers, pulling out the still‑steaming metal slug. “The socks,” she said.

Girlie asked for permission to rewind the video. Permission was granted. Then she aimed her laser pointer toward a corner of the frame, where one of the girl’s feet was barely visible.

By this point four women had left the room, one crying. The red light pinned to the girl’s ankle and did not shake.

“The socks feature an illustration of a main character from the animated Disney film Frozen,” Girlie continued. “Judging from the scale of the TV remote control next to her leg, I would estimate a girl’s size three or four.”

Girlie got the job. So did the young man who threw up before her; he’d thrown up, but he hadn’t paused the video. That was good enough. She was proud of herself, but knew she had no real reason to be; the hiring managers weren’t all that picky, in the beginning.

*

Think of yourself as someone who makes our social media family a safe and fun place for everybody, that early job description read. The best candidates will not only be able to apply content policy and execute handling procedures with consistency and efficiency but will also be able to identify subtle differences in the meaning of digital communication and accurately enforce the client’s terms of use. Here at Reeden we believe that a community that learns together, grows together—you will actively benefit from and participate in employee assistance programs, program reporting initiatives, and appropriate training to foster your well-being and the well-being of our entire employee family. You may find that we love a good party, and you can usually expect one to be happening on campus somewhere! Now come on, we need your full concentration—it’s time to imagine what it’s like being a Content Moderator!

At the beginning there were user‑experience researchers floating around—UXRs, they were called—forever doing some study or another, there to observe the lives of the moderators, the better to improve said lives. There was the Day in the Life method, in which a UXR would shadow one moderator throughout the workday, sitting po-faced at her side while she rewound a video of someone’s partial decapitation, scribbling in a notepad. There was card sorting, a method meant to “uncover the user’s mental models, to improve informational architecture,” in which the UX researchers would hand the moderators a deck of index cards labeled with categories—sometimes examples of content to be moderated, like disemboweled horse, sometimes pictures of famous Hollywood actors, to be categorized according to the character they most embodied: action hero for Schwarzenegger, romantic lead for Clooney, et cetera. Girlie looked at the film still of Schwarzenegger as the T‑800, put him in the maternal role model category. She didn’t receive any feedback about what this said about her informational architecture.

Every single one of the UX researchers was a middle‑class woman. Oh, they were diverse—white women both Bostonian and Scandinavian, Black women both Southern American and West African, Asian women both Korean Californian and Indian immigrant—but in that Tolstoyan way of all happy families being alike, all middle‑class women looked the same to Girlie.

The solutions they found were the same too: the studies, ultimately, all found that the moderators could benefit from a variety of wellness tools, as well as regular team‑building events to encourage decompression and foster camaraderie. Girlie hadn’t asked for weekly cake parties. Girlie had replied “a raise” when a researcher asked how her job could best be improved. She didn’t get a raise; the funds, it seemed, had been allocated into the social activities budget. They got a karaoke machine.

By the time the initial flurry of these researchers and tech reporters had dissipated, employees were merely encouraged to attend two wellness coaching sessions a year, and at least one wellness group session a month. Every few months or so the company still held a Mental Health Symposium, full of indispensable tips and crucial training about how to protect her internal space, set up boundaries, and not hesitate to make use of the resources at hand, nearly all of which were helplines that went straight to an answering machine, or infrequently monitored email addresses programmed to auto‑send a PDF about anger coping skills, mostly recommending different forms of deep breathing.

After the first year was over, Girlie skipped both her one‑on‑one visits and the group sessions, all the cake parties and symposiums. She had a job to do, and she was doing it. If she hadn’t been as productive, perhaps the mandatory wellness sessions would have been more stringently enforced—but the company policy, in general, was that if you looked like you were doing okay, they left well enough alone. Even if you didn’t look like you were doing okay—someone at another site, it was rumored, had a heart attack at their desk and died there; there was a new moderator at that desk within the week—they left well enough alone. There was just so much to do.

At first, there were no official specializations in the moderation department—“our aim is to upskill all of our moderators,” the Bay Area manager had said in those early days, “so they can action all potential abuse types.” But there was an unspoken understanding that certain employees were particularly gifted in specific genres of abuse, and so in training they would be partnered with—or would become, themselves—unofficial subject matter experts.

No one wanted the title Hate Speech Expert or Head of Child Sexual Abuse on their LinkedIn, but it was known amongst the moderators that if you were struggling with a racist abuse issue, you went to Maria (one of the four moderators named after the Virgin; this one was ex–grad student Maria—to be distinguished from the other three, who were all older Pinay women, none of them particularly good at identifying tendencies toward racial abuse, in particular their own).

If you had trouble judging whether or not a video contained scenes of animal torture, you went to Robin, the uptight young Pinoy nerd everyone said was the youngest employee Reeden (well, not Reeden, exactly) had ever hired, recent UC Davis grad, never talked to anyone, didn’t flinch or cry like that one white guy—last one left on the floor—who quit after seeing the video of someone beating a bag of puppies to death with a baseball bat.

If murder and gore were your bugbears, you went to Rhea—former ER nurse, McCain Republican, self‑proclaimed gun enthusiast, sometimes found cooing on the phone to her geriatric Italian husband, and who’d started moderating after her retirement, just to bring some extra cash in. Rhea, alternately known as Ray, not quite a deadname since Rhea switched back to it whenever she felt the privileges or protections of being Ray were superior, usually when they had to accommodate a senior manager visit. Rhea was a consummate capitalist ex‑provinces girl in the school of Girlie’s own mother, which was to say: nothing was dead if value could still be extracted from its ghost.

The young Cambodian American trainee who’d thrown up, Vuthy, was Rhea’s apprentice now, following her around like a puppy, showing her pictures of shotgun wounds and asking for her advice, so they’d often be found chatting pleasantly in the hallway about the difference between birdshot, buckshot, and slug, how to look for the scalloped edge around a wound, what powder tattooing looked like at close range.

And if child sexual abuse was your issue—whether someone being fucked within an inch of their life was a four‑foot‑eleven adult Asian woman or a child speaking choppy French to appeal to his expat clientele, how many photos of naked children wearing angel wings constituted a cache of pornography, which ever‑changing code words to flag on which ever‑disappearing Passport Bros message boards, which cities were the hot spots for meeting places for affiliates and the newly initiated, how to differentiate between a right‑wing nutcase endlessly SWAT‑ing a laundromat from an actual potential trafficking bust—you went to Girlie. Girlie didn’t have any apprentices.

Later, perhaps in recognition of the need for aspirational examples of workplace advancement, the specialists were officially called SMS. Subject Matter Specialists; the word Experts being a touch too self‑actualizing. They even received a raise: one dollar more per hour. The Vegas site was the highest‑performing location in the national network; they hovered around a 97 percent accuracy rate, just a percentage point short of the company’s set target, which was never achieved by any site, and was in effect a built‑in justification for all future budget cuts and layoffs—they were perpetually ever so slightly underperforming, always as a direct result of the previous year’s budget cuts and layoffs. Accuracy rate meant that when the people in Vegas thought something was child trafficking, it was child trafficking. When the people in Boston or Dallas thought something was child trafficking, it was usually just a brown mom and her mixed‑race kid in Target. The managers had talked a lot about learning algorithms. Clearly the concept—that is to say, learning—hadn’t quite reached critical mass in human beings yet, but one could be hopeful about machines.

Girlie’s own accuracy rate was around 99.5 percent. The old judicial joke about pornography was, in Girlie’s case, both the earliest of life lessons and the ultimate performance review. When it came to child sexual abuse, Girlie knew it when she saw it.

As for why so many of them were Filipino—well, what was there to say that hadn’t been said in 1765; in 1899; in 1946; in 1965? The bootstraps way of putting it was to say they excelled, frankly, in the manner of people who had been formed to excel in these very specific theaters: because they spoke and read good English, because they respected chains of command, because they kept a positive attitude, because they would take a fifth of an American worker’s pay, and most of all: because they were familiar. They knew Americans; what they liked, what they didn’t, the ditties they sang, the food they ate, what they looked like when they were horny, what they looked like when they were dying, the psalms that struck their hearts, the way their women set their curls, the shift of air around a man before his fist hit flesh, the hours of night when God was least visible. There was no other country in the world, no other people in the world, better suited to the content moderation of America. And from America, to the world. Ad astra, et cetera.

Well, why not? Her mother was a nurse, her aunts and distant cousins all nurses and maids and cleaners scattered everywhere from Jeddah to Singapore to Rome. There was a glowing line that trailed through them, all the way back to that first early Pinay, a twentieth‑century almost‑girl, being taught by a white woman how to administer quinine to a malaria patient.

A glowing line through them, like a lava‑bright rift in the earth, which traveled all the way to Girlie: there in the office park, cleaning the feeds of their stubborn stains of rape and bludgeoning; there in the Vegas desert, far from home; there in that soul‑shaped place called heredity.

__________________________________

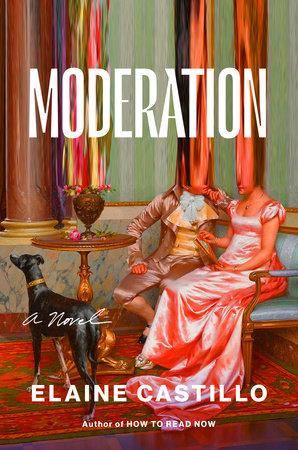

From Moderation by Elaine Castillo, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. © 2025 by Elaine Castillo.