“Our beloved Lazarus has gone to sleep, yet I will go and wake him . . .”

“Why, O Lord? Have I done something to displease you?” Lazarus whispered in his darkness. Apprehensive, the Messiah rolled away the stone, called to Lazarus, and waited. After only a few seconds, Lazarus emerged, blinded by the blaze of light that struck his eyes. When they started unwinding his white wrappings, he realized that the miracle had actually been performed. He had fallen sick, and the illness became so severe that death had come as a mercy, carrying him o” to a place without any pain or su”ering. He spent four days there in nonexistence. He had been sleeping, and then he had been awakened; secure, and then disturbed; floating in the beyond, and then the Messiah arrived and brought him out. “Why, O Lord? Have I done something to displease you?”

The whistle of the electric teakettle startled Mr. N. He left his papers on the table and got up to switch it o”. He turned to face the window, where a black fly caught his attention, perched motionless on the wall above one of the panes of glass. He reached out to catch it, but it flew away and landed on the wall over the other windowpane. Mr. N stepped toward it, and the fly circled back again. Mr. N smiled. He drew the curtain back halfway and opened the window, sliding one pane behind the other. The fly cocked its head and gave him a wink out of the corner of its eye before swooping through, leaving no trace.

The sky spilled down an enormous quantity of light that struck Mr. N all at once. His eyelids dropped involuntarily as the light poured onto his face, his neck, his chest, his arms. The light stopped at his waist, which was as far as the window allowed it to reach. Looking down, Mr. N backed away two steps from the window and drew a long, deep breath—like someone about to jump. Even with his eyes averted, however, the white metal bars forming their squares over the window reminded him of their existence by casting shadows across the floor tiles.

A car horn blared, startling Mr. N. Other horns followed, proclaiming their own excellence. Then the flock of horns raced o”, without any shepherd to guide them or any sheepdog to bring them back to the straight and narrow. Their hooves crushed everything in their path: passengers, pedestrians, children, residents of the neighboring buildings, sparrows, trees, shops.

Mr. N pressed his face against those white iron squares and looked down, annoyed. Why all these cars, and where could they be going? The clock showed 10:25. Employees were at their oðces, children were at their schools and universities, mothers were in their kitchens, he was in his room. So who were all these people, and why were they all going for a drive together?

More than once over the years, it had occurred to him to abandon this apartment on account of its terrible location and the noise that poured through the window and into his ears at all hours. But Andrew—the tall building manager with the friendly face—had resisted the idea, had tried to dissuade him, suggesting that Mr. N move instead to a room on the opposite side of the complex. There, he would forget about the street and look down on the beautiful garden in the rear courtyard. Still, Mr. N had hesitated. He wasn’t a person who liked change. He might be fed up by the noise, but his fear of giving up the window was greater. What if this window proved to be his last, and giving it up meant he was giving up the world as well? From here he could take the pulse of the outside world and look out upon God’s creation. He saw time racing by, the departure of each day. He enjoyed the air and seeing the sky. If he ever missed the sight of nature, he went down to his hotel’s garden at night when it was empty and at rest. He greeted the plants and their blossoms, he embraced the trees, and he touched the stone benches, inspecting what time had stolen from them. And if his tired body protested, he just went down to the end of the hallway outside his room. He would get a chair, open the window, and sit there absent-mindedly, looking out. He hated leaving his apartment. He only ever braved the streets to visit his mother. No, Mr. N found his lodgings quite suðcient; he walked from room to room, content with his home and his guests, feeling no need for the world beyond.

Mr. N closed his window and dropped its white curtain back into place. The insolent light retreated, the noise began to behave itself, and the traðc congestion melted away. Mr. N went over to his teakettle, produced a mug that had his name written on it in black ink, poured the tea, and drank. The flavor was strange. The tea was cold and the color of water. No matter. He pulled out the chair and sat back down to his papers.

Our beloved Lazarus awoke with the taste of fire in his mouth. He cleaned his teeth and his tongue and all around behind his lips. He gargled water repeatedly, and still he couldn’t get rid of the taste of fire and decay. He realized his salvation lay in water alone. That is why he had always loved it so much . . .

The pencil lead snapped under Mr. N’s hand. At once he snatched up the shard between his fingertips and placed it in a small plastic yogurt container. He had set aside two such containers, the first of which was completely full, the second nearly so. One day, thought Mr. N eagerly, he would set about counting them, one by one, so he would know how many pencils he’d gone through. He stopped short at the idea that the lead of each pencil sometimes broke more than once. No matter. He could estimate the average number of times that a single pencil broke, and then make a simple calculation to arrive at the approximate number of pencils.

And yet to yield to the approximate made him grimace. He liked precision and hated rough estimates. The approximate was arbitrary, the arbitrary was random, the random was chaotic, and chaos was a killer. Mr. N liked to cut away the imprecise, as he did with his pencils when he sharpened them, shaving their tips into points to make their lines clear and defined. Pens? Pens were unacceptable. Pens could leak, flooding pages with smothering ink. Ink behaved like a dictator: ordering, forbidding, controlling, brooking no dissent. Lead, meanwhile, was merciful, quick to forgive mistakes. Whatever your soul was brooding over, lead would let it speak. Ink soiled the white page; lead dissolved upon the surface, exactly as pain dissolved in the act of writing . . .

Mr. N let his pencil fall and read what he had written. Why, Lord? Have I done something to displease you? The meaning of his words escaped him, and he read them again. It didn’t help. He took the page and calmly tore it into four pieces, trying to make them all the same size.

Then came an unexpected knock at the door. Mr. N looked up, but otherwise remained frozen in place, the better to encourage his caller to think he wasn’t home and so go away, back to wherever he came from. But the knock came again, quick and soft, and Mr. N knew it was Miss Zahra come to examine him. Cracking open the door, Miss Zahra whispered with her wonted delicacy and even tenderness, “Mr. N, may I come in?”

Mr. N smiled and nodded. Miss Zahra eased herself inside and saw Mr. N sitting at his papers. She set what she was carrying on the table where he was working and then tapped his shoulder with a benevolent hand to invite him to stand. She looked over at his bed nearby, and Mr. N got up, following her eyes to sit on its edge, where she wanted him. He was smiling, and she was smiling too. She came in smiling and went out smiling, and in between she kept smiling no matter what he did. And after she left? Mr. N wondered. And after Lazarus awakened?

Miss Zahra lifted his arm. She tapped his elbow and passed her soft fingers along his bulging, blue veins. Then she bent over . . .

“Ouch!” cried Mr. N. “What sharp teeth you have! The better, I suppose, to nibble through these veins of mine that you seem to love so much.”

She apologized and pressed the spot where she’d hurt him. The pain vanished. Miss Zahra then returned to the table and gathered up her things, casting a quick glance over the papers lying there.

“I’m so happy you’ve gone back to writing,” she said. “I’m dying to read what you’re working on.”

“Where are you going?” Mr. N asked, hurrying after her. “Aren’t you going to stay with me any longer?”

With a laugh, Miss Zahra raised her eyes to the ceiling in the customary gesture of refusal. Then she slipped out, closing the door behind her with the same gentleness she had shown upon entering. As she left, Mr. N glimpsed a small hole in her nylons. The run started underneath her foot and stopped at her anklebone. If only she put a drop of clear nail polish on it, he thought, it would stay where it was and not threaten to sneak farther up. That’s what Mary would do, who was so unlucky with her nylons, as she put it; Mary with her rough hands, scraped raw by housework for Mrs. Thurayya and her family.

One Sunday morning, before anyone else was up, Mr. N had caught Mary sneaking her fingers into her mouth to moisten them before holding open her stockings to insert her feet. The stockings were a gift from Mrs. Thurayya after years of service, and Mary dreaded snagging them. Two translucent, skin-toned silk stockings. Mary wore them proudly on Sundays and holidays, taking pride in them before her friends and relatives, who had to make do with thick, dark, opaque stockings of cotton or wool. Whenever her stockings were too tight at her knees, Mary would reach underneath the tight elastic bands and roll the edges down to ease the red bracelets they left on her white flesh after a day of wearing them. Each Sunday, Mary would put on her silk stockings and try to sneak o” to the nearby church for mass—because if Mr. N woke up and started crying before she left, she would have to pick him up and rock him back to sleep in her arms. Sometimes, though, he would cling to her bosom and only pretend to fall back asleep because he relished being taken along—the warmth of the church, the faint illumination, the scent of incense, the hopeful imploring voices. But he would drift off for real the moment he heard the hymns and the prayers, and then come around only when Mary stood to receive the Eucharist and to present her little N at the altar for the priest to bless with a splash of holy water on his head.

Had Miss Zahra noticed the run in her stockings and worn them anyway? That would be a black mark against her, thought Mr. N. Until today her appearance had always been impeccable. Neat and well turned out, giving o” a scent that was a mix of rubbing alcohol and soap. Just like Thurayya. As though she were a new doll, fresh out of the package. Thurayya wouldn’t tolerate any scratch, any wrinkle, any speck of dust. She was all clipped fingernails, trimmed hair, elegant clothes, earrings, necklaces, and rings. Even when she slept. Even when she dreamed. Traces of her perfume—that penetrating French perfume, Femme—would permeate every corner of the apartment. In both summer and winter, the scent would emanate from her room in the morning when she opened her door after applying her hair spray, the final step in her lengthy, daily beauty routine.

Thurayya had ruined Mr. N’s taste in women. Despite the detachment and aversion he felt for her at the time, he couldn’t help being influenced by her tastes. What he wanted in a woman was someone who could look as clean and orderly as Thurayya on the outside, yet contained all the abundance, plenty, and warmth that Mary had offered Mr. N. Miss Zahra did have some of Thurayya’s coldness, it was true, balanced by some of Mary’s kindness, but Mr. N would hardly have called her his ideal. Still, when she came back, he would point out the matter of her damaged stocking. It wasn’t right for a woman like her to go around looking sloppy. And when he brought it up, he would also insist that she stay a while.

_________________________________

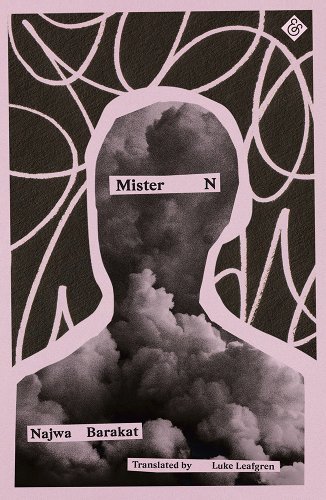

Excerpted from Mister N by Najwa Barakat, translated by Luke Leafgren. Reprinted by permission of And Other Stories. Copyright (c) 2022.