It is often debated whether art is a mirror or a window, but this is a false dichotomy. Great art is both surface and symbol, reflecting our world even as it frames another one. And there is depth to art’s superficiality, just as symbol constitutes a form of façade. If those who go beneath the surface and read the symbol do so at their peril, as Oscar Wilde warns, perhaps that risk is sometimes worth the reward.

In the pantheon of artists who bridge this paradox, whose work functions demonstrably as both window and mirror, few offer more delicious, perilous rewards than Aubrey Beardsley. Astonishingly prolific in his short life—he died of tuberculosis at just 25—Beardsley cuts a tragic, Keatsian figure of the Art Nouveau, but I also want to call him the most sophisticated horny schoolboy in art history. (Sex and death! We’re off to a great start.)

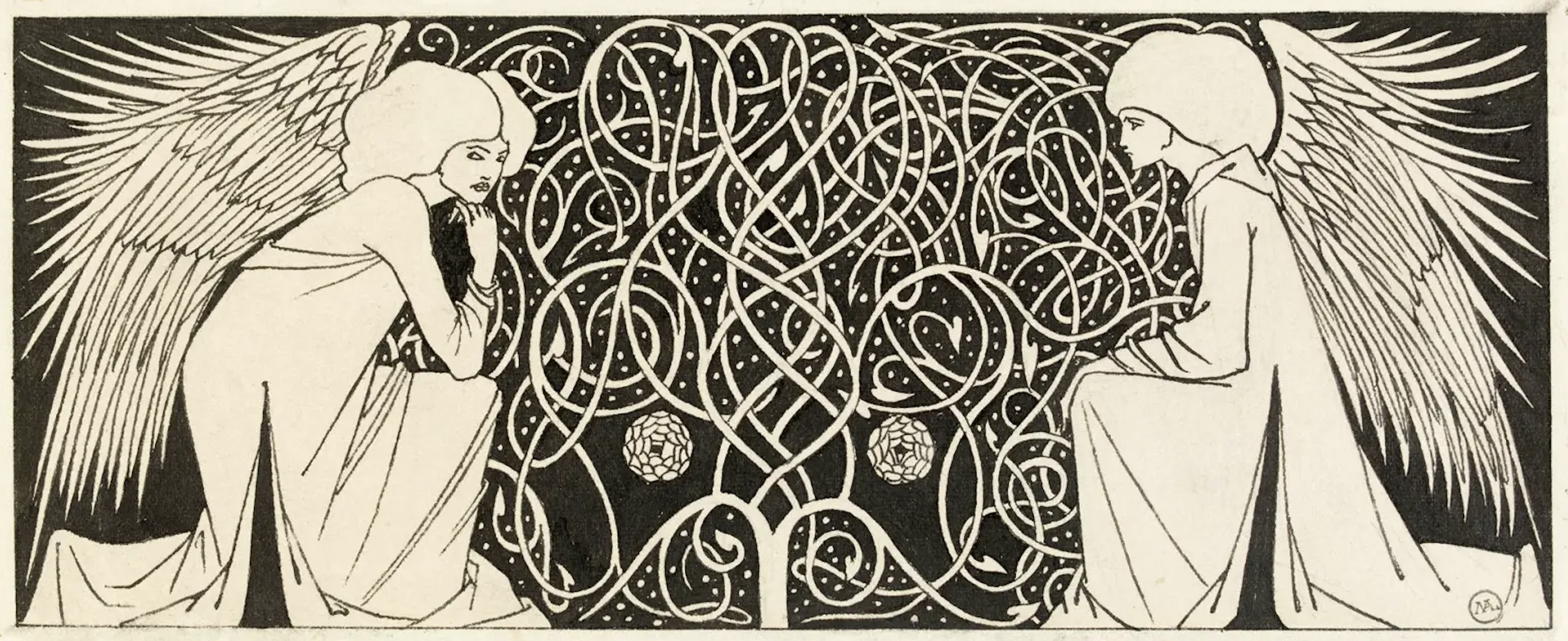

Perhaps it is the schoolboy quality of Beardsley’s oeuvre that has tended to brand him an illustrator—which he was, of course, and a great one, modulating his signature style to reflect the subject at hand. Compare his pictures for The Rape of the Lock to those for Le Morte D’Arthur, and you’ll notice the former’s swirling baroque flourishes, the latter’s stiffer geometry evoking an almost stained-glass quality.

Illustration for The Rape of the Lock, 1896.

Illustration for The Rape of the Lock, 1896.

And yet both series are instantly recognizable as the work of Aubrey Beardsley. Those stark, ornate black lines, flat in their depth, grotesque and immaculate, offer a vista into a singular hand controlled by a singular mind, quite often a delightfully twisted one. Insofar as Beardsley is an illustrator, he is not an accompanist but a specialist in the duet. He is an artist in equal measure. Wilde himself understood this, inscribing a French copy of Salomé prior to their partnership on the English edition: “For Aubrey: the only artist who, besides myself, knows what the dance of the seven veils is, and can see that invisible dance. Oscar.”

Later Wilde would grow more ambivalent, worried Salome’s pictures outshone its text, and in places even mocked him. I say this as an ardent admirer of Wilde: these were reasonable concerns. Beardsley’s drawings for Salome represent the zenith of his brief, superabundant career—of his ability to shine simultaneously as a collaborative illustrator and independent artist, to render mirror and window at once.

*

Stylistically, Beardsley’s pictures for Salome are among his most derivative and original. In the sharpness of their lines and great swaths of black and white, we see the well-documented influences of Japanese woodcuts and Ancient Greek vase-painting. And yet, Beardsley’s work bridges these grand traditions of East and West with such fresh dynamism and taboo as to be undeniably, and ultimately definitionally, Nouveau.

For all the nudity and arousal stripped from the second version, Beardsley still manages to sneak in some naughty details.The mix could not be more appropriate for a scripturally subversive play. Salome’s dominant rhetorical mode is figurative, teeming with circular similes so overt they come to possess a litanic quality, lulling the reader, like Herod, into classically gendered expectations for Salome to trounce.

The moon is “like a woman” and “like a princess who has little white doves for feet”; princess Salome is “like a dove that has strayed” and “like a silver flower.” Salome later compares the moon to “a little silver flower,” while Herod exclaims Salome’s “little feet will be like white doves. They will be like little white flowers that dance upon the trees.”

Beardsley captures Wilde’s symbolic conflations with clever metadramatic flair. Figures in the Salome set are often androgynous, frequently mirror-images, sometimes of ambiguous identity, and infused with self-reflexive playfulness. Beardsley’s moon is Salome—but also Wilde, openly caricatured as such in The Woman in the Moon (frontispiece) and A Platonic Lament.

The Woman in the Moon, from Salome.

The Woman in the Moon, from Salome.

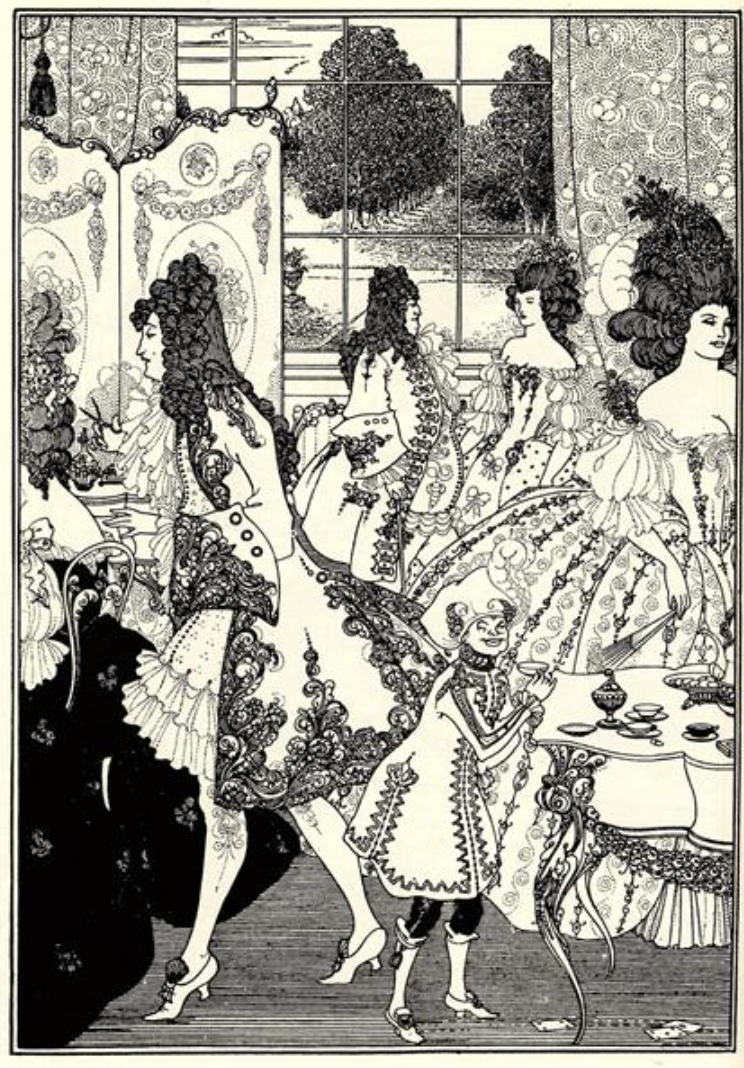

Both of these drawings, like most in the series, are “framed” by a three-line border that creates a window-esque effect. In Enter Herodias, the most expressly theatrical of the group, the stage doubles the picture-window to form a kind of mirror. Crescents decorate the girdle and hair of stately Herodias, who, flanked by lackeys and positioned dead center with these bulbous, anti-gravity breasts, has assumed the lunar role. Her grotesque left-hand lackey is appropriately moon-headed, while the Page of Herodias coyly holds her make-up and a mask at right.

Sporting a jester-like owl mask himself, Wilde plays the authorial showman, the rogue-sage, gesturing to the scene from the foreground with a copy of Salome in his other hand (some scholars argue it’s the playbill). “Only in mirrors should one look,” he seems to say, echoing Herod—“for mirrors do but show us masks.”

Enter Herodias was one of several pictures for Salome that its publisher, John Lane, bowdlerized for its licentious content, prompting Beardsley to fig-leaf the page in the first edition. And yet Wilde’s outstretched hand—notably propped up by Beardsley’s tripartite “signature device”—also points to a phallic candelabra, iconographically connecting Enter Herodias to both the hermaphroditic border design for the title page and The Eyes of Herod, where Beardsley gives the lascivious Tetrarch Wilde’s face.

Enter Herodias, from Beardsley’s illustration portfolio, c. 1906-1912.

Enter Herodias, from Beardsley’s illustration portfolio, c. 1906-1912.

It was likewise due to Lane’s censorship that Beardsley made two versions of The Toilette of Salome. In the original version, she sits bare-chested at right, a classically feminine beauty, facing her vanity on the left. Mischievous, masked Pierrot—a frequent subject of Beardsley’s with whom he personally identified—lords over her, dangling a powder brush that, along with the mask, ties him to the effeminate page in Enter Herodias and cheekily suggests that Beardsley himself is the chief artist behind Salome’s allure.

Beardsley captures Wilde’s symbolic conflations with clever metadramatic flair.A few more details support this interpretation. There is Pierrot’s positioning: in front of the huge, literal window at center, and turned away from the vanity mirror. The window’s three-line sash also echoes the overall picture’s three-line border, explicitly connecting the literal and figurative windows.

Note that in the second, sanitized version of The Toilette, the literal window is smaller, on the opposite side of the room from Pierrot, and partially obscured by blinds. While Beardsley retains the same three-line picture border, he also flips the composition more broadly, with Salome to the left and the vanity at right. This time though, Pierrot and Salome have both turned away from the mirror—itself now angled away from, rather than toward, you the viewer.

The two versions are explicit mirror-windows of windows and mirrors, with the re-do a symbolic protest of the original’s censorship. Lane’s constraints, Beardsley implies, have diminished the power of his art both by stifling his own expression (the smaller, blinded window to the side) and ability to reflect Wilde’s work (the oblique mirror into which no one looks)—but have not snuffed it out entirely. For all the nudity and arousal stripped from the second version, Beardsley still manages to sneak in some naughty details, like the Marquis de Sade’s book and Pierrot’s pocket-scissor phallus.

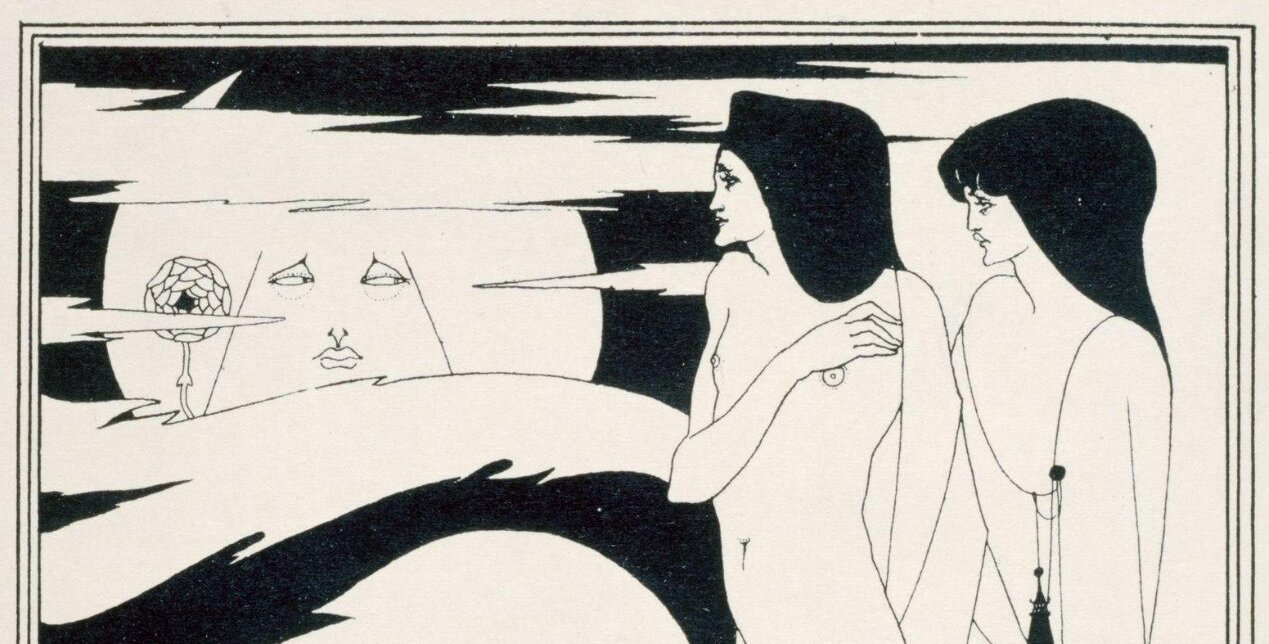

A Platonic Lament, c. 1907.

A Platonic Lament, c. 1907.

He accomplishes something similar in A Platonic Lament, its title alone giving cover for a scene that is anything but. Superficially, it is one of the set’s more directly representational pictures, illustrating the Page of Herodias mourning the Young Syrian’s suicide. There’s a line in the play, though—the last in the page’s eulogy—that makes me think Beardsley has another allusion in mind:

“He was my brother, and nearer to me than a brother. I gave him a little box full of perfumes, and a ring of agate that he wore always on his hand. In the evening we were won’t to walk by the river, and among the almond-trees, and he used to tell me of the things of his country. He spake ever very low. The sound of his voice was like the sound of the flute, of one who playeth upon the flute. Also he had much joy to gaze at himself in the river. I used to reproach him for that.” [Emphasis mine.]

Oscar Wilde was too fond of the myth of Narcissus, of its half-hidden homoeroticism, for this not to be a pointed reference, and Beardsley’s composition reinforces it. The nude Page of Herodias leans over the Young Syrian’s corpse like Narcissus over his pool, as if for a kiss, dipping “his arms to embrace the boy he sees there.” Their faces are uncannily similar, and the Young Syrian’s black burial shroud is almost water-like, framing the dead reflection.

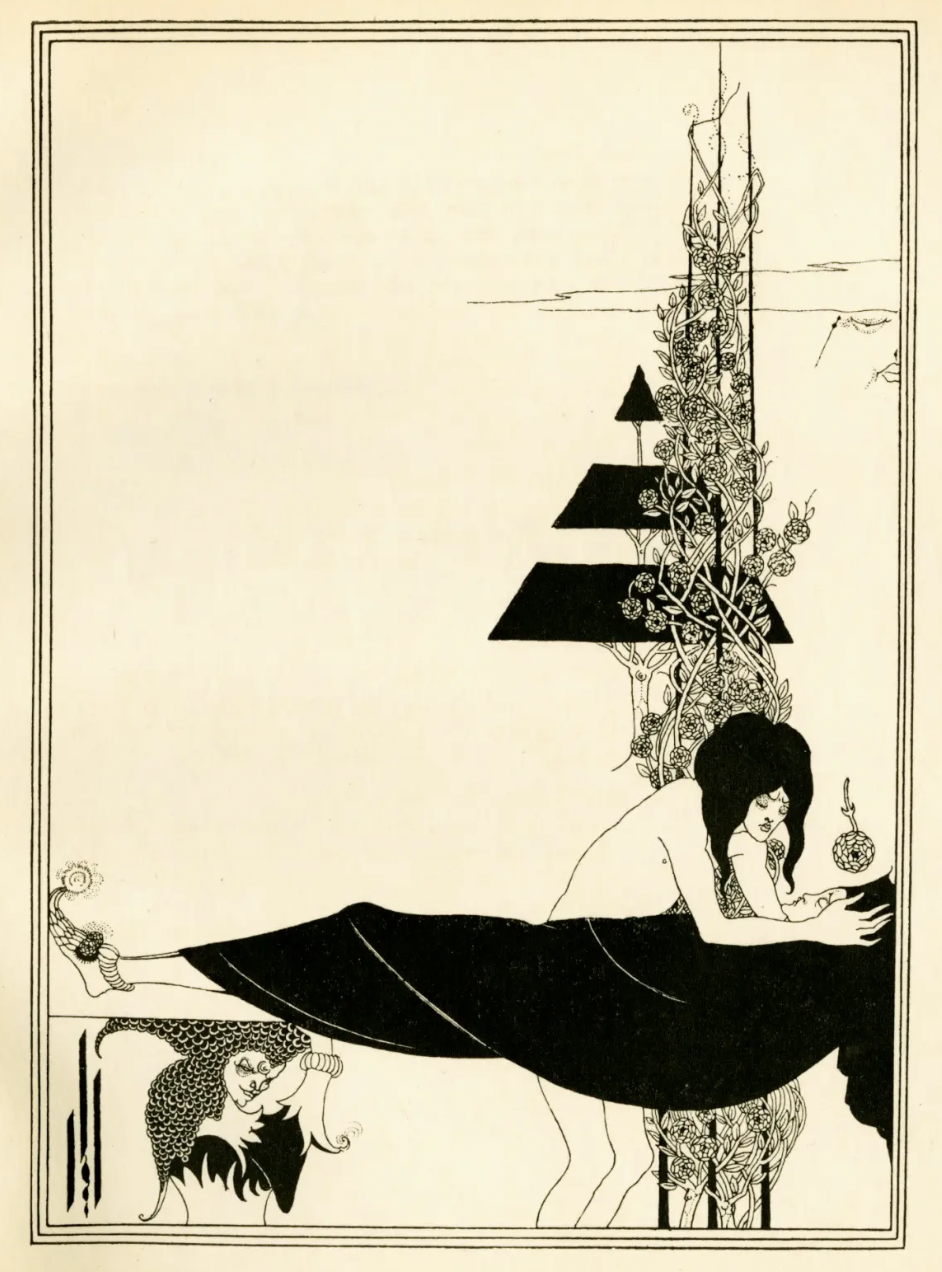

This position is strongly echoed by Salome holding Iokanaan’s head in The Climax (a more appropriate title), his blood flowing into a flower-sprouting pool, and to a lesser extent in John and Salome and The Peacock Skirt, all of which feature cunningly mirrored facial features.

The half-hidden Wilde moon in the upper right of A Platonic Lament sheds a floral tear, both recalling Narcissus’s fatal transformation and connecting the scene to The Woman in the Moon with homosexual undertones. In the context of subsequent Narcissan lamentation, the way the page reaches protectively across that phallic tassel suggests he longed to keep the Young Syrian safe from the moon—from Salome—not in humane disinterest, but for the love that dare not speak its name.

The moon’s floral tear is a rose, not a narcissus. It’s not perfect, but then few of Beardsley’s—or Wilde’s—references are; there was too much danger in clarity. There was too much danger anyway. When Wilde was arrested for “gross indecency,” Beardsley lost his job as art editor of The Yellow Book by sheer association. He would succumb to his illness less than two years later, but not before illustrating The Rape of the Lock, Lysistrata, and The Savoy, among other projects. All told, in spite of the terrible brevity of his life, his catalog contains well over a thousand images, mirrors and windows all.

_______________________________

Bibliographical note: in lieu of footnotes, the main image and biographical source for this piece was Linda Gertner Zatlin’s extraordinary Aubrey Beardsley: A Catalogue Raisonné (Yale, 2016). Images in the Dover Edition of Salome (1967) were also consulted, and this was the primary text source. The line from Ovid’s Metamorphoses was translated by Rolfe Humphries (Indiana, 1955).