History has a way of deceiving us. We know how the story turns out. In focusing on the steps that led to a result, we can’t help but form the impression that the outcome was inevitable.

We forget that the people in the middle of the most momentous events in our history had no idea what would happen.

That is why I like suspending the usual viewpoint of history from 30,000 feet up and taking events down to ground level. In my latest book, The Lincoln Miracle: Inside the Republican Convention That Changed History, that means the floor of the Wigwam, a freshly built, massive auditorium of fragrant, unfinished wood, and in the crowded, smoky, tobacco-juice-stained saloons and hotel rooms of Chicago during one week in May 1860.

We find there a story unfolding so astonishing—and so crucial to the ultimate survival of the United States, and the destruction of slavery—that some who were there thought the invisible hand of the Almighty shaped the outcome. I consider what happened that week a miracle.

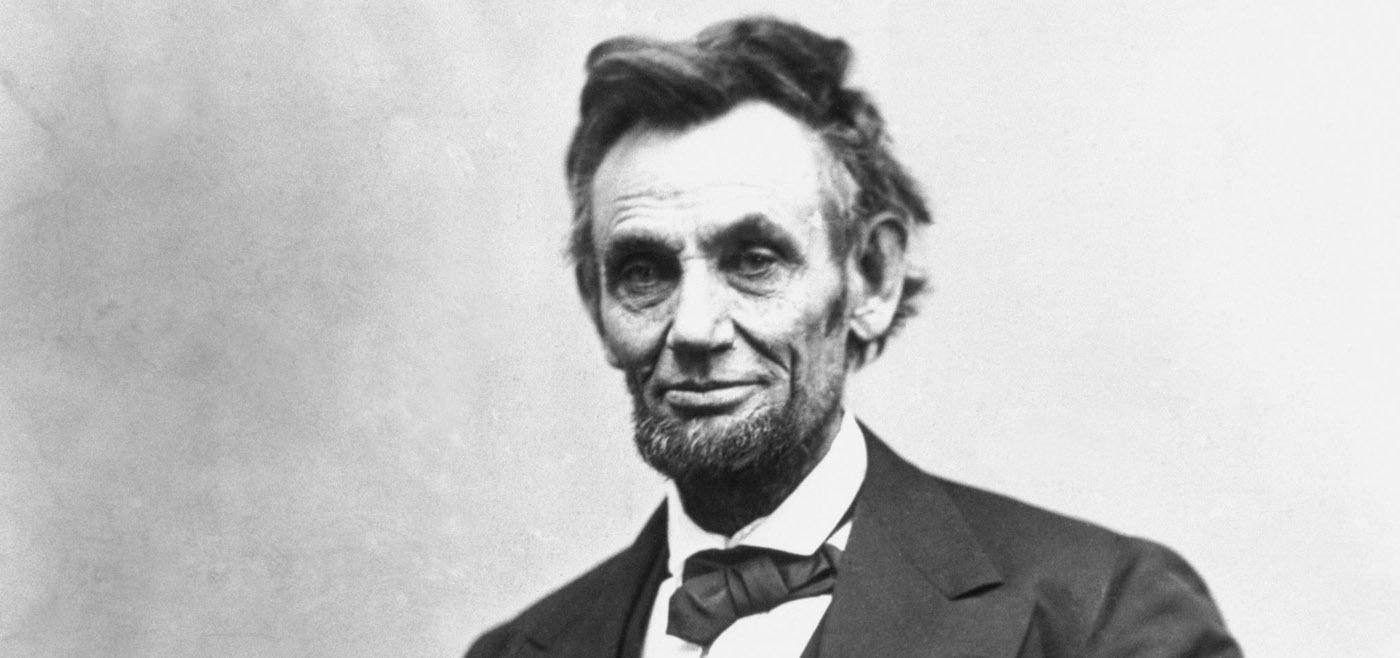

Given Abraham Lincoln’s stature—he regularly tops lists of the greatest US presidents—his rise to prominence seems a foregone conclusion. But it was anything but. This is the week that propelled him to greatness. Without his subsequent role as president, no one would have meticulously recorded his life’s story. As historian Mark E. Neely Jr. wrote, “Had Abraham Lincoln died in the spring of 1860, on the eve of his first presidential nomination, he would be a forgotten man.”

We may not appreciate what a long shot Lincoln was going into the convention that nominated him.

The resumes of other candidates towered over his own. He had grown up poor and had next to no formal education. He told vulgar—at times, dirty—jokes. He had not held elected office for more than a decade. His one two-year term in Congress had been regarded by many as a failure. He had lost two campaigns for the Senate. His executive experience was pretty much limited to running a two-man law office.

“Just think of such a sucker as me as President!”Lincoln himself had told people he did not think himself fit for the presidency, and two years earlier he declared, with roaring laughter, “Just think of such a sucker as me as President!” Even while lining up support, Lincoln did not formally declare his presidency. He told a close ally: “The taste is in my mouth a little.”

In fact, Lincoln’s chances seemed so remote that the leaders of the Republican National Committee approved Chicago as the convention site in part because they thought it was neutral ground. No major candidate, they concluded, hailed from Illinois.

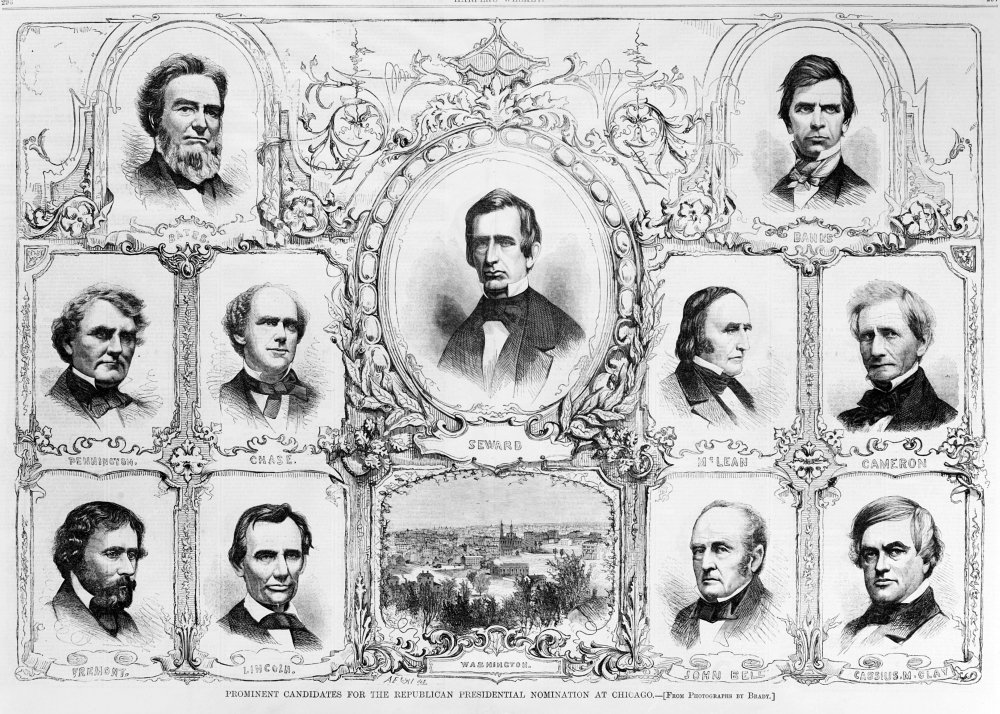

In a lithograph centerspread of the candidates published on Saturday, May 12, 1860, Harper’s Weekly played Lincoln’s picture on the bottom with the also-rans; its written description of Lincoln was dead last among all the candidates. At best, people were talking about Lincoln as a possible vice-presidential nominee, coming as he did from an important swing state.

From Harper’s Weekly, May 12, 1860.

From Harper’s Weekly, May 12, 1860.

Front and center, with the biggest picture and first and longest write-up, was the superstar of the Republican party, the former governor of New York and current US Senator William Seward.

Seward was regarded as the founder and father of the Republican Party, a bold opponent of slavery and defender of the rights of immigrants, and he was managed by a brilliant political strategist named Thurlow Weed, who could make or break senators and presidents. He had more money behind him than any candidate. Under our modern system, he would have rolled through the primaries. Lincoln wouldn’t have had a prayer.

But in 1860, Seward’s strength was deceptive.

The previous October, abolitionist John Brown had raided a federal armory and planned to provide enslaved people with guns for a violent insurrection against whites. While Brown was apprehended and hanged, the incident infuriated the South and terrified many voters in the North. Many thought all this slavery talk was putting impossible pressures on the political system and threatening to break the nation in two, igniting a bloody civil war. And nobody was more famous for anti-slavery rhetoric than William Seward. Party leaders worried about that. Though Lincoln had made many of the same points against slavery, he was far less known to the voters—thus, less scary.

Today’s readers will no doubt find a haunting familiarity in the mood of 1860. Politics seemed to have broken down. Those who disagreed could no longer discuss issues.On top of that Seward had openly supported immigrants and was close to Catholic leaders, something that turned off a sizable portion of the Republican base, who feared that rampant immigration was helping Democrats steal elections and destroying America from within. Former members of the American Party, often called the Know-Nothing Party, might well bolt from the Republicans if they nominated Seward. Lincoln’s position on immigrants, meanwhile, was so little known that some people assumed he was a Know-Nothing. (In truth, Lincoln despised the movement.)

Today’s readers will no doubt find a haunting familiarity in the mood of 1860. Politics seemed to have broken down. Those who disagreed could no longer discuss issues; they talked past each other and increasingly looked to violence to get their way. One major party suffered bitter internal divisions. Even the selection of a House speaker, normally a rote affair, dragged on. Many viewed Washington as a festering swamp of corruption run by elites who had lost contact with the common people.

One of the most striking things that quickly became clear in my research was that these men gathered in Chicago were not choosing a candidate on the basis of who might make the best president in that climate of crisis. Their biggest concern, by far, was who would get the most Republicans elected, which meant power, jobs, and money.

The pro-Lincoln Chicago Press and Tribune appealed to this naked self-interest in an editorial aimed at arriving delegates: “Constables are worth more than Presidents in the long run, as a means of holding political power. … We look to Mr. Lincoln to tow constables and General Assembly [members] into power … The gods help those who help themselves.”

There was something else going for Lincoln that wasn’t immediately apparent to the national press. Though he was a minor figure nationally and had been defeated repeatedly, he had built an intensely loyal following in Illinois. With home-field advantage, they made an enormous difference in Chicago.

Early in the convention, the “moderate” alternative to Seward appeared to be a Missouri judge named Edward Bates. His supporters argued he would calm the South and negate all threats of succession, and he had the backing of some powerful forces—notably, the most influential newspaper editor in the country, Horace Greeley, who came to Chicago to undermine Seward for blocking his political career.

Unfortunately for Bates, German immigrants were dead set against him, because he had flirted with the Know-Nothing Party. Prominent Germans went so far as to hold their own national convention that same week just down the road from the Republican one, sending a terrifying signal to the delegates. Though German immigrants made up only a small percentage of Republican voters, that was enough to sway elections in many Northern states. The delegates did not dare go with Bates. I called my book The Lincoln Miracle in part because so many things beyond Lincoln’s control slotted into place perfectly to advance him. There are too many to recite in this short essay that I recount in the book.

Some events that week seem almost spookily fortuitous. On Thursday, May 17, Seward had won a series of test votes and seemed poised to win the nomination. But tally sheets had not arrived at the rostrum. Rather than wait just a few minutes, hungry delegates adjourned for the day—leaving the Lincoln men the opportunity to work all night cutting deals. On such slender threads hang the fate of nations.

They also evidently forged counterfeit tickets to the convention hall. When Seward supporters arrived at the Wigwam after marching in the streets the next morning, they found Lincoln men occupying their seats—giving delegates an oversized impression of the support in the hall for Lincoln during the voting for president.

The greatest miracle, of course, was the nature of the man nominated. Delegates knew Lincoln as a strong speaker and a loyal Republican. But they could have had no idea of his strengths of stubborn willpower, subtlety of mind, literary genius, and political brilliance. Lincoln was arguably the only one of the candidates who could have saved the nation in its time of greatest peril and ended the moral abomination of chattel slavery.

For that reason, one journalist covering the convention later argued that the men at the Wigwam were “the unconscious instruments of a Higher Power.” I hope you join me on the wild ride of that week to experience how great a miracle Abraham Lincoln was.

________________________________

The Lincoln Miracle, by Edward Achorn, is available now from Grove Atlantic.