Mirion Malle: “Let's Talk About Mental Health Without Pointing Blame”

The Author of This is How I Disappear Speaks With Sophie Yanow

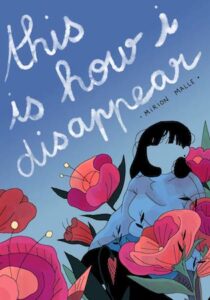

Mirion Malle (This Is How I Disappear, translated by Aleshia Jensen and Bronwyn Haslam) and Sophie Yanow (The Contradictions) spoke to one another as part of D+Q Live, a fall event series by the graphic novel publisher Drawn & Quarterly. The occasion was Malle’s second English-language release and first work of fiction, This Is How I Disappear, of which Yanow has written:

“A stunning portrayal. Mirion Malle gives us just enough to keep going—just enough to root for Clara as we stumble with her through anxiety, depression, and a culture of shame. The journey is well worth it.”

Both spoke from their homes —Malle in Montreal and Yanow in Marin County, California—touching on queer representation, organizational strategies for cartoonists, the way each approaches fiction versus non-fiction, and more.

*

Sophie Yanow: This Is How I Disappear is masterfully drawn and written and I also found the story to be really relatable in so many ways. I wrote down some of the things that resonated: Not being able to name for yourself what you’re experiencing and why. The series of repeated attempts it sometimes takes to get help. The financial and time constraints that create barriers to professional help. The necessity and limits of friendship when it comes to depression and the importance of a network of support. How at times we can provide support to others and at other times, we can’t. And of gentle intervention and accepting help.

This book brought up all of those things for me in a very profound way. I’d like to turn it over to you with an easy question which is, why did you write this book? Was it a story you felt compelled to explore personally, or did you feel there was a need for this book to exist for others or something else entirely?

Mirion Malle: Before This Is How I Disappear, I had never done much fiction but I always wanted to. I started off making nonfiction books, sort of by accident. So when the chance arose, I did a few things for Expozine, Montreal’s zine fair. At the time I was finishing my Master’s degree or I was working for a non profit, so I didn’t have much free time. But that first zine became the first 30 pages of This Is How I Disappear.

With this book, I wanted to talk about the stigma of mental illness without pointing blame. It’s not that people are bad-intentioned, it’s just we don’t know what to say because we don’t talk about mental health.

SY: I didn’t read the original zine. Was the therapy session the original starting point of the story?

MM: Yeah, I think I re-drew a few details but I didn’t make many changes.

SY: I’m curious if that was the first scene that came to you, because so much of the rest of the book doesn’t take place in that setting. It’s kind of external to the professional setting.

MM: I really wanted the book to be focused on Clara’s point of view, so she appears on almost every page. We experience the story through her and I thought that would set the story tone. The opening scene kind of gives the reason why Clara is depressed, even if it doesn’t make it explicit at this moment. Also, this isn’t the main message of the book but I wanted to talk about the difficulty of accessing good mental health care, how expensive therapy is. So yeah, that scene shows why she doesn’t go back to her therapist.

SY: Even when you find a therapist, the relationship doesn’t always work out.

MM: It takes such a long time and such a lot of money, even if you find a low cost option. Maybe you can only find a Freudian psychoanalyst when you want a system-based approach or something.

SY: Right. So the book really centers female and queer friendship. I know that you’ve written about the Bechdel test and I was curious if this was something that you set out to intentionally portray or if it just feels like a natural reflection of life to you and happens to satisfy the Bechdel test, as it were.

MM: It’s kind of both because I always think about who I put in my stories and there’s a political aspect to representation. But also, I write about stuff that I know and observe. I don’t want to create work that copies reality precisely but rather something that brings out the feeling of real life, of lived experience.

I’m a lesbian so all of my friends are lesbians or women, most of them bisexual women, and the men, some of them are straight but most of them are queer. That’s just the way it is because you find yourself with people who are like you. So, Clara is also a lesbian and her friends are queer because it would be weird for her to only have straight friends. All the same, her colleagues, her friends at work, are straight.

So that’s an instance where I drew what I saw in my own life. But I also crave queer and lesbian content because I don’t see that very often. I think it’s very political to show our reality and not necessarily center our stories around homophobia. It’s important to show queerness existing in other settings.

SY: Yeah, absolutely. Could you talk about your writing process? I’m curious if you write prose first or if you make sketches or if you go directly to ink or if you pencil and if you pencil, how tight are your pencils? What are the stages?

I crave queer and lesbian content because I don’t see that very often. I think it’s very political to show our reality and not necessarily center our stories around homophobia.

MM: Thank you, I don’t really get asked that a lot, so I’m happy because I like to talk about how I work. I’m very badly organized and I often lose all my original work, but with this book, I was determined to be more organized.

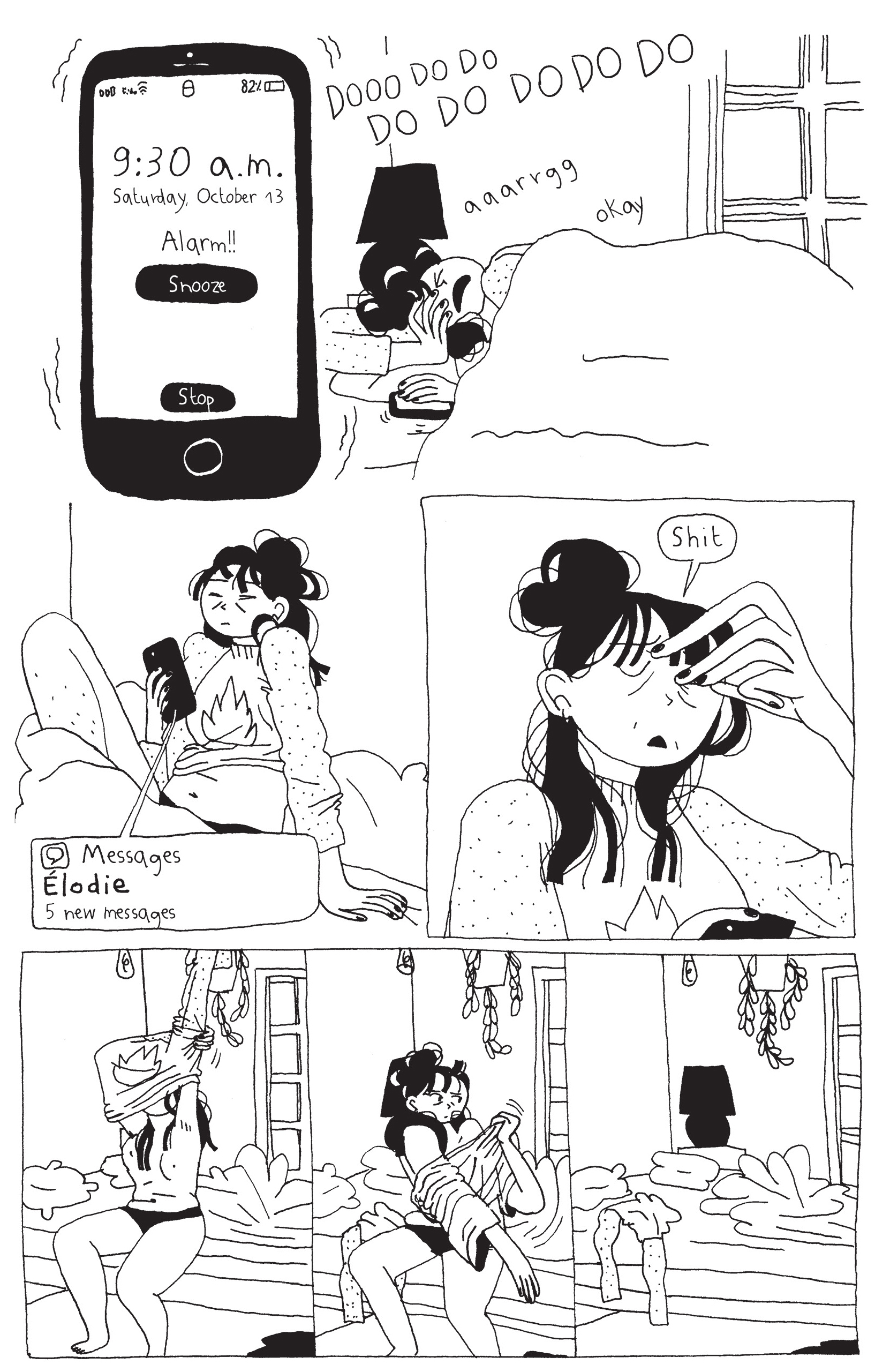

I have a notebook where I draw sketches of the characters, write all the stuff I need to do and some ideas for the scenes. All of that is very rough, so I don’t forget later, because I’m very good at forgetting. Then I write the more detailed version when I’m doing the story boarding. For this book, since it was in black and white, I drew with a Rotring. It’s very, very thin and the ink is very nice. It’s very expensive but it breaks so easily. So, love/hate relationship with this pen. I typically do a very rough, very basic sketch because my art style gets too stiff if my sketches are too detailed.

Since I’m writing while drawing, I try to draw the pages next to each other so I can have an idea of how the reader is going to go through the pages and compose them in the best way for telling that part of the story. I really enjoy working like that. Before Disappear, since I was always on deadline, sometimes I just went with ink and cleaned up as needed in Photoshop. I wanted a cleaner art style in Disappear. The book I’m doing right now, I’m drawing in pen, so I have to do a kind of detailed sketch and I’m hoping that it’s not going to look too stiff. It’s a challenge but I think I’m learning and improving with every book.

I just list out the pages that I sketched and here I do a little cross when it’s inked and color it in when the page has been colored. My deadline is coming up soon and you can see that it’s going to happen with a lot of difficulty. But it’s nice because I can see where I am and not panic at the end of the day, feeling, “Oh, I did nothing today.” Do you feel that way?

SY: Oh yeah, I absolutely relate to that. Yeah.

MM: Yeah, you have to write down what you’ve done because it’s so easy to be hard on yourself and feel that you have done nothing even when you worked all day. This system makes it all more concrete. I also use my cell phone Notes app. I’ll think of something while I’m sleeping and wake up to jot it down.

SY: Now I feel like you’ve contradicted the idea that you’re disorganized. I do that too with the highlighters and checking things off like it did take me a long time to develop that and also to acknowledge that, you know what, actually that is important for organization. Well, sometimes it’s just about getting it done, right? You finish the page, you scan it, and okay, great.

You touched on this a bit in the opening: a lot of your other work is nonfiction and you have a Master’s in Sociology and so I’m curious if you feel that your research and your nonfiction work informed your process for Disappear.

MM: With nonfiction, I really work like if I was doing an essay. At the beginning of my university career, I did something very weird in France called a classe prépa, a preparatory class where you study a lot of literature and philosophy and English, but 17th century English. So, I can say for example, “tinsmith” but I always forget very common words.

Every week, you have a different test where you have six hours to write an essay so I learned to write very quickly and very efficiently. I do exactly the same thing when I’m doing the didactic non-fiction comics and I start directly with the ink so it’s just text and inking. My non-fiction art style is not the same at all. I want it to be more playful and funny and to go straight to the point.

When I started Disappear, I was very afraid of being trapped in didactical comics, so I was like, “This isn’t a didactical comic, it’s not ‘how to deal with depression.’ It’s a story. It’s a story.” But now I can see that there are some links between those two parts of my work.

SY: You move really fluidly between different types of drawing in the book and I really love how you’re willing to simplify things and make the forms of the characters more graphic when they’re farther away or draw them suddenly with manga eyes to create a certain effect or move focus from a character crying to these graphical tears.

In my own work, I made these rules when I went to fiction with The Contradictions. In my nonfiction work, I’m much more willing to be all over the place and have graphic elements. When I went into fiction I felt I had to follow the rules derived from traditional narrative film where we don’t break out visually in the same way.

Can you talk a little bit about your relationship to moving in and out of style, relative to the nonfiction work? And also I’m just curious if you set those kinds of rules for yourself.

MM: That’s interesting because when I read The Contradictions, I saw the filmmaking composition choices because I was very much inspired by filmmaking and by cinema when I was doing Disappear. The first time I understood really what a comic could do was when I read Debbie Dreschler’s Daddy’s Girl when I was maybe twenty. The art is really telling the story. Also, the art constructs the ambience, the very heavy atmosphere of the book. That’s when comics made sense to me. And I do think it’s like cinema.

Comics and cinema, it’s not word plus image where the images are illustrating the word or vice-versa. Both pieces – word and image—are telling something. That’s what I really, really love about comics and it’s very much cheaper than doing cinema unfortunately because you can tell the story with those two things. I would be very lost if I just had to write a text-based book. In a comic, the form is helping to tell the story at the same level as the text. For example, the manga eyes. I was an avid reader of shojo manga when I was a teenager and I still love them very much, even if I always reread the same 1990s shojo.

Before starting to do this book, I reread Nana by A Yazawa, and one of my other favorites is Gals! by Mihona Fujii. I’m always talking about those two because they were so important to me when I was growing up. Nana is kind of sad and heartwarming but it’s more of a dramatic story. Then Gals! is a funny manga. I owe a lot to those mangakas. I never read shonen. When I put a smiley on the face of a character, it’s because smileys are kind of blank just like how emojis are blank.

SY: Yeah, manga artists are so advanced. There’s just so much that comes out of this experimentation. I think it’s so fluid when you’re using those tools. I find myself thinking, “Oh man, that looks really fun.”

And it’s also very effective. It feels very natural, like you’re allowing yourself to do what feels right. I kind of alluded to this in my blurb for the book, which is that Clara is going through this depression where she’s not fully capable of seeing what’s going on with herself, doesn’t know what she’s struggling with. Having experienced depression myself, that felt very true. You do a really amazing job for the reader. You give us just enough information that it feels like we are in a similar state to Clara as we read. Was that something that you were thinking about as you worked on the book?

MM: That’s why I wanted the book to follow Clara. It’s always from her point of view. She’s never not there. I wanted the reader to be with her and to see everything from her perspective.

Take for example, her Montreal friend group. We see them a lot during the beginning of the book . . . They don’t really understand Clara and they don’t know how to talk to her, but they’re there and they care about her and they’re not bad people. They’re just not in the right place at the right time but also maybe they’re not ready to help. I didn’t want it to be, “she’s good, they’re bad.” I wanted the reader to understand that Clara isn’t in a place where she can give them what they want, explain herself to them. She doesn’t have the energy.

It’s not because she doesn’t like her job. It’s not because she has a broken heart. It’s because she lived through a trauma but also it’s not entirely because of that. It’s all of that and capitalism and the inaccessible mental health care system. Everything is adding to her state of mind . . .

SY: Yeah.

MM: I think the day-to-day details reveal more than a therapist’s session.

__________________________________

This is How I Disappear by Mirion Malle is available now from Drawn & Quarterly.

Sophie Yanow

Sophie Yanow is an artist and writer based in the San Francisco Bay Area. The Contradictions is her first book with Drawn & Quarterly, the webcomic of which won an Eisner Award and was nominated for the Ringo, and Harvey awards. Yanow is also the author of What is a Glacier? and War of Streets and Houses. Her comics have appeared in The New Yorker, The Guardian, Fusion, Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Nib. She has been a MacDowell Colony Fellow, and her translation of Dominique Goblet’s Pretending is Lying received the Scott Moncrieff prize for translation from French. Yanow has taught at the Center for Cartoon Studies, the New Hampshire Institute of Art, and The Animation Workshop in Denmark.