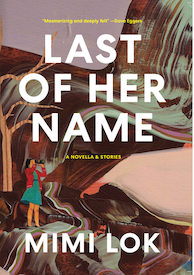

Mimi Lok on Writing in (and For) the Margins

The Author of Last of Her Name in Conversation with Dave Eggers

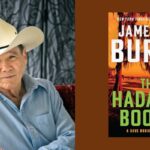

Dave Eggers and Mimi Lok discuss Lok’s debut story collection Last of Her Name. Eggers is the author of The Parade, and the cofounder (with Lok) of Voice of Witness, a nonprofit that amplifies the voices of marginalized people through an acclaimed oral history book series and a national education program.

*

Dave Eggers: How does your fiction writing connect, if at all, with the work you do with Voice of Witness?

Mimi Lok: For a while I think I separated the two unnecessarily, maybe out of a sense of protectiveness towards each one, I don’t know. But in both cases, it’s about illuminating experiences and perspectives that otherwise live in the margins. In my own writing, I’m drawing on experiences that are mainly rooted in my culture and in the Chinese diaspora, but at the end of the day it’s fiction—whatever was real has been filtered through so many layers of invention. Voice of Witness books are centered around edited oral histories from people whose lives have been impacted by the criminal justice system, migration, and displacement—these are real people’s lives, and it’s a huge responsibility to work on these stories and do justice to them. If I fail in my writing, on the other hand, I’m mostly just letting myself down.

DE: The Voice of Witness books have something in common with a good, cohesive short story collection. In both, you’re immersed in a specific world, but you see it through multiple perspectives. Your book is like that. There’s a cohesion to the collection overall that’s rare. Not that story collections need to be thematically linked—I really think they can be wildly disparate and unconnected—but there’s a specific pleasure in reading a collection that has an unseen glue holding it together. For Last of Her Name, I think it’s that sense of dislocation. None of the characters are quite at home.

ML: The characters and stories in Last of Her Name are part of a larger diasporic experience. They’re connected by their sense of disconnection, both physical and emotional. I wanted to explore what it really means to belong, and to connect—with intimates, with strangers, in the moment, and across time and place. Some of the characters are connected in tangible ways, sometimes it’s in that unseen glue you mention. And on some level I also think of them as imagined reincarnations of each other: This is the life X might have had, if they’d been born in this time and place and body instead of that one.

The title speaks to themes that run throughout the rest of the collection: the things that women and girls do inherit, the histories we’re born into.

There’s definitely a kind of liberation in writing a story collection. I appreciate being able to dive deeply into one person’s experience in a story, and not have to worry so much—especially as a minority writer—about the assumption of it being the main representative of an issue or a community, since the other stories alongside it offer various kinds of contrasts and connections.

DE: The title story, Last of Her Name, is such an emotional gut punch. It’s a dual narrative of two young women from very different times, both in extreme circumstances. And they happen to be mother and daughter. The daughter, Karen, is assaulted in 1980s England. Her story alternates with her mother’s experience as a girl in WWII Hong Kong. You have roots in Hong Kong and you grew up in the UK, so I know this story has some personal relevance.

ML: That story initially came out of the idea of the secret lives of parents—that there are things we’ll never know about our parents’ lives, particularly immigrant parents and the things they keep from their children for various reasons—whether that’s out of shame, or protectiveness, or because they simply don’t have the words to share certain, painful experiences. In Last of Her Name I wanted to portray this Chinese immigrant family primarily through the experiences of Karen, who’s 12, and her mother June/Jin-Jin—as a girl in WWII Hong Kong and later as a wife and mother in the UK. To explore how their lives are starkly different but also how they unknowingly echo and parallel each other.

It’s also a story about what it feels like to live as an immigrant in a place for a really long time, and no matter how much you try to fit in and adapt and believe in the systems that your adopted country runs on, it’s hard to shake off that deep-down mistrust of those systems. You don’t believe they’re actually there to help you when you need them.

DE: I love the title so much, especially without the article “the.” Without it, the word Last almost acts like a verb—it has a kind of imperative urgency.

ML: Last of Her Name comes from a line in the story, when June, who’s pregnant at that point, is wondering whether she’s having a boy or a girl, and reflects on lineage and namelines and inheritance, and how, where she’s from, women are left out of all of that. So the title of that story speaks to themes that run throughout the rest of the collection: the things that women and girls do inherit, the histories we’re born into. Histories that include trauma and oppression, but also resilience and resourcefulness.

DE: When I read “The Woman in the Closet,” I had that unmistakable feeling you get when you’re reading a perfect story. I don’t think I breathed until it was over. Where did that story come from?

ML: About ten years ago I came across a short news article about a woman in Japan who’d been arrested for sneaking into a man’s home and living in his closet. When the police asked why she’d done it, she said that she had nowhere else to live. I tried to find out more, but every piece I found recycled the same couple of paragraphs. It didn’t make sense to me that there wasn’t more on the story, because there was so much more I wanted to know. I kept thinking, Who is this woman? I couldn’t get her out of my head.

DE: The story is the length of a novella—though I think that category somehow begs for a story to be ignored. But this length is so crucial, anything from about 60 to 100 pages, because in so many cases it’s the perfect length to explore one character in one situation, and to delve deeply there without having to introduce multiple characters or subplots. It allows a kind of hypnosis that’s only possible if you can read it in one sitting.

ML: I didn’t set out to write such a long story, but I knew I wanted to give her as much space as possible, to give her her due, in a way. The story was really my way of responding to the eight million questions I had about her, like, how did her life come to this? Who was she before all of this? What did she do every day? So I started imagining this whole life for her, and eventually she evolved into the character of Granny Ng. The more I thought about her, the less bizarre her actions seemed, and the more they occurred to me as simply what she had to do for survival but also for her own sense of dignity and autonomy.

Writing this story, I thought a lot about what a person needs to fuel a fantasy, and the roles that absence and omission play in that.

DE: You moved the story from Japan to Hong Kong in the near future.

ML: Right now in Hong Kong, we don’t have tent villages, but given the increasing rich-poor divide and the general instability of the past few months, I don’t think it’s at all beyond the realm of possibility.

Out of the whole collection, that story is probably the one I was most nervous about, so I’m really happy that it’s resonated with people.

DE: Why were you nervous about it?

ML: Honestly, I thought, who besides me going to give a shit about Granny Ng? I thought that readers might not relate to an elderly person as the protagonist of a long story. And then there’s the premise—I thought, some people are just going to think this is ridiculous! Even if a story is inspired by a real life event, it doesn’t make it automatically plausible in fiction. And I thought about society’s general apathy towards older people, sometimes disgust—and the tendency to make them invisible, especially older women. I still don’t fully understand it, but I think it’s easy to dehumanize people whose mere existence taps into deep-seated fears of abandonment and mortality.

DE: “The Wrong Dave” is about an engaged British architect who, first of all, has a great name.

ML: There are basically no stories in this century featuring anyone named Dave.

DE: He begins receiving emails from Yi, a wedding crasher he met in briefly in Hong Kong. And she might have mistaken him for someone else. For some reason epistolary stories are hard to pull off, but yours works perfectly. It might be the strangeness of it. Both characters are permitted to be odd.

ML: Writing this story, I thought a lot about what a person needs to fuel a fantasy, and the roles that absence and omission play in that. Email is such a weird, inadequate medium of communication, and because so much is left out and what remains is magnified, sometimes way out of proportion, it becomes really fertile ground for misunderstanding and obsession. So while we see the various aspects of Dave’s life and follow him around a fair bit, I wanted the reader to have limited access to Yi i.e., mainly through these email exchanges. I wanted her to be tantalizing to the reader as well as to Dave—not exactly in the same way, but enough to believe why Dave would be so drawn to her.

DE: It’s also interesting how Dave and Yi express themselves in totally different ways over email. Yi’s is like this unfiltered stream of consciousness—you get the feeling she’s not even thinking about what she’s writing—but Dave is extremely neurotic and careful about every word, as if he’s worried he’s going to expose himself in some way.

ML: For Yi, she wants to be seen—she uses the emails to try and make a human connection but she’s also screaming her grief and anger into the void. As someone who tends more towards Dave’s type of email neurosis, it was really freeing to write in her voice in this way. For Dave, he definitely hides behind the medium. Its remove from the physical world, combined with its immediacy, lets him continue feeding his secret correspondence and his romanticizing of Yi without consequence—or so he thinks.

DE: Your story “I Have Never Put My Hope in Any Other but in Thee” follows a teenager and her stepmother over the course of an afternoon in Hong Kong. The story is full of moments where you see the characters wanting desperately to connect with each other but totally miss the mark. We see this during a pivotal moment that involves the sound installation “Forty Part Motet” by Janet Cardiff. Why did you choose to include that specific piece?

ML: The seed for that story came from the first class I ever took for my MFA program, with Peter Orner. He asked us to write something in response to a work of art. I chose “Forty Part Motet” and wrote maybe a page or two about it. I’d seen it a few years before in London, and I remembered just being blown away by it.

You enter this white room and see forty black speakers arranged in a circle on stands. Each speaker is playing the recorded voice of one singer performing this beautiful, haunting choral piece, and you walk around experiencing different aspects of the song. The piece is phenomenal—there’s the music itself, but also the feeling of intimacy from hearing each individual voice singing.

Each time I’ve gone to see the piece over the years, I see the same reactions: people around me have been overcome with emotion, weeping, or squeezing their eyes shut. Or they look like they’re in total ecstasy. I’ve never seen anything like it. So I suppose it wasn’t just the piece but the effect it has on people that made such a lasting impression on me.

Some time after the class assignment I ended up working that piece into a story about a teenager, Audrey, and her ex-opera singer stepmother Vivienne walking around Hong Kong when they’re meant to be visiting Audrey’s sick dad in hospital. At one point they end up visiting this sound installation and each of them have really different responses to it. I thought it would be interesting to use the piece to explore art and emotion—being able to access it, or not, and being paralyzed by the conformity of it in some ways.

DE: What are your hopes for the book?

ML: Particularly close to my heart, because I’ve been there, are readers who don’t often feel that they see themselves and their experiences depicted in literature. I hope that they can find some kind of recognition in these stories, and that it inspires them to seek out more stories, or create space for them, or write those stories themselves.

———————————————

Last of Her Name by Mimi Lok is now available from Kaya Press. Copyright © 2019 by Mimi Lok.

Dave Eggers

Dave Eggers is the author of seven bestselling and award-winning books. He is also the founder and editor of McSweeney’s, an independent publishing house based in San Francisco that produces a quarterly journal and a monthly magazine (The Believer). In 2002, he cofounded 826 Valencia, a nonprofit writing and tutoring center for youth in San Francisco, which has spawned six affiliate 826 centers nationally.