Michiko Kakutani on

Why We Love Books

And on Relevance of Arendt's The Origins of Totalitarianism Today

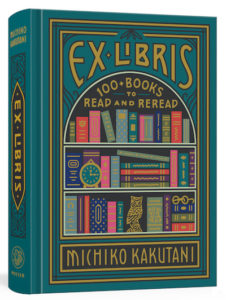

Below is an excerpt from the introduction of Kakutani’s new book EX LIBRIS: 100 Books to Read and Reread and from an essay on Hannah Arendt.

As a child, the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright August Wilson recalled in a speech that he was the one in his family who wanted to read all the books in the house, who wore out his library card and kept books way past their due date. He dropped out of high school at age fifteen, but spent every school day at the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh reading history and biography and poetry and anthropology. The library would eventually give him an honorary high school diploma, and the books he discovered there, he said, “opened a world that I entered and have never left,” and led to the transformative realization that “it was possible to be a writer.”

Dr. Oliver Sacks credited the local public library he knew as a child (in Willesden, London) as the place where he received his real education, just as Ray Bradbury described himself as “completely library educated.” In the case of two famous autodidacts, Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, the books they read growing up indelibly shaped their ideals and ambitions, and gave them the tools of language and argument that would help them shape the history of their nation.

The pleasure of reading, Virginia Woolf wrote, is “so great that one cannot doubt that without it the world would be a far different and a far inferior place from what it is. Reading has changed the world and continues to change it.” In fact, she argued, the reason “we have grown from apes to men, and left our caves and dropped our bows and arrows and sat round the fire and talked and given to the poor and helped the sick—the reason why we have made shelter and society out of the wastes of the desert and the tangle of the jungle is simply this—we have loved reading.”

In his 1996 book, A History of Reading, Alberto Manguel described a tenth-century Persian potentate who reportedly traveled with his 117,000-book collection loaded on the backs of “four hundred camels trained to walk in alphabetical order.” Manguel also wrote about the public readers hired by Cuban cigar factories in the late nineteenth century to read aloud to workers. And about the father of one of his boyhood teachers, a scholar who knew many of the classics by heart and who volunteered to serve as a library for his fellow inmates at the Nazi concentration camp Sachsenhausen. He was able to recite entire passages aloud—much like the book lovers in Fahrenheit 451, who keep knowledge alive through their memorization of books.

Why do we love books so much?

These magical brick-sized objects—made of paper, ink, glue, thread, cardboard, fabric, or leather—are actually tiny time machines that can transport us back to the past to learn the lessons of history, and forward to idealized or dystopian futures. Books can transport us to distant parts of the globe and even more distant planets and universes. They give us the stories of men and women we will never meet in person, illuminate the discoveries made by great minds, and allow us access to the wisdom of earlier generations. They can teach us about astronomy, physics, botany, and chemistry; explicate the dynamics of space flight and climate change; introduce us to beliefs, ideas, and literatures different from our own. And they can whisk us off to fictional realms like Oz and Middle-earth, Narnia and Wonderland, and the place where Max becomes king of the wild things.

*

When I was a child, books were both an escape and a sanctuary. I was an only child, accustomed to spending lots of time alone. I read in the cardboard refrigerator carton that my father had turned into a playhouse by cutting a door and windows in the sides. I read under the blankets at night with a flashlight. I read in the school library during recess in hopes of avoiding the playground bullies. I read in the backseat of the car, even though it made me carsick. And I read at the dining room table: because my mother thought books and food were incompatible, I would read whatever happened to be at hand—cereal boxes, appliance manuals, supermarket circulars, the ingredients of Sara Lee’s pecan coffee cake or an Entenmann’s crumb cake. I read the recipe for mock apple pie on the back of the Ritz crackers box so many times I could practically recite it. I was hungry for words.

The characters in some novels felt so real to me, when I was a child, that I worried they might leap out of the pages at night, if I left the cover of the book open. I imagined some of the scary characters from L. Frank Baum’s Oz books—the Winged Monkeys, say, or the evil Nome King, or Mombi the witch who possesses the dangerous Powder of Life—escaping from the books and using my bedroom as their portal into the real world, where they might wreak havoc and destruction.

Decades before binge-watching Game of Thrones, Breaking Bad, and The Sopranos, I binge-read Nancy Drew mysteries, Black Stallion novels, Landmark biographies, even whole sections of the World Book Encyclopedia (which is how my father fine-tuned hisEnglish, when he first moved to the United States from Japan).

In high school and college, I binge-read books about existentialism (The Stranger, No Exit, Notes from Underground, Irrational Man, Either/Or, The Birth of Tragedy), black history (The Autobiography of Malcolm X; The Fire Next Time; Manchild in the Promised Land; Black Like Me; Black Skin, White Masks); and science fiction and dystopian fiction (1984, Animal Farm, Dune, The Illustrated Man, and Fahrenheit 451, Childhood’s End, A Clockwork Orange, Cat’s Cradle). My reading was in no way systematic. At the time, I was not even aware of why I gravitated toward these books—though, in retrospect, as one of the few nonwhite kids at school, I must have been drawn to books about outsiders who were trying to figure out who they were and where they belonged. Even Dorothy in Oz, Alice in Wonderland, and Lucy in Narnia, I later realized, were strangers in strange lands, trying to learn how to navigate worlds where few of the usual rules applied.

In those pre-internet days, I don’t remember exactly how we heard about new books and authors or decided what to read next. As a child, I think I first heard of Hemingway, Robert Penn Warren, James Baldwin, and Philip Roth because there were articles by or about them (or maybe photos) in Life or Look magazine. I read Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring because my mother was reading it, and T. S. Eliot’s poetry because my favorite high school teacher, Mr. Adinolfi, had us memorize “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” I was one of those readers who experienced many things first through books—and only later, in real life, not the other way around.

“You read something which you thought only happened to you,” James Baldwin once said, “and you discovered it happened 100 years ago to Dostoyevsky. This is a very great liberation for the suffering, struggling person, who always thinks that he is alone. This is why art is important.”

*

As Hannah Arendt observed in her 1951 book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, two of the most monstrous regimes in human history came to power in the 20th century, and both were predicated upon the destruction of truth—upon the recognition that cynicism and weariness and fear can make people susceptible to the lies and false promises of leaders bent on unconditional power. “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule,” she wrote, “is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.”

What’s alarming to the contemporary reader is that Arendt’s words increasingly sound less like a dispatch from another century than a disturbing mirror of the political and cultural landscape we inhabit today—a world in which the president of the United States, Donald J. Trump, does a high-volume business in lies (three years into his White House tenure, The Washington Post calculated, Trump had made 16,241 false or misleading claims), and fake news and propaganda are cranked out in industrial quantities by Russian and alt-right trolls and instantaneously dispersed across the world through social media.

Nationalism, nativism, dislocation, fears of social change, and contempt for outsiders are on the rise again as people, locked in their partisan silos and filter bubbles, are losing a sense of shared reality and the ability to communicate across social and sectarian lines.

Arendt’s words increasingly sound less like a dispatch from another century than a disturbing mirror of the political and cultural landscape we inhabit today.

This is not to draw a direct analogy between today’s circumstances and the overwhelming horrors of the World War II era but to look at some of the conditions and attitudes—what Margaret Atwood has called the “danger flags” in Orwell’s 1984 and Animal Farm—that make a people susceptible to demagogues and dictators, and nations vulnerable to tyranny.

Here are some of the fundamental points Arendt made about the “hidden mechanisms” by which totalitarian movements dissolve traditional political and moral understandings, and the behavior evinced by totalitarian regimes, once they come to power.

One early warning sign is a nation’s abolishing of the right of asylum. Efforts to deprive refugees of their rights, Arendt wrote, bear “the germs of a deadly sickness,” because once the “principle of equality before the law” breaks down, “the more difficult it is for states to resist the temptation to deprive all citizens of legal status.”

Leaders of totalitarian movements, Arendt observed, “can never admit an error,” and fanatical followers, suffering from a mixture of gullibility and cynicism, will routinely shrug off their lies. Hungry for simplistic narratives that explain a confusing world, such audiences “do not trust their eyes and ears” but, instead, welcome the “escape from reality” offered by propaganda, which understands that people are “ready at all times to believe the worst, no matter how absurd, and did not particularly object to being deceived,” because they “held every statement to be a lie anyhow.”

Because totalitarian rulers crave complete control, Arendt pointed out, they tend to preside over highly dysfunctional bureaucracies. First-rate talents are replaced by “crackpots and fools whose lack of intelligence and creativity is still the best guarantee of their loyalty.” Often there are “swift and surprising changes in policy” because loyalty—not performance or efficacy—is paramount.

To ratify followers’ sense of belonging to a movement that is making progress toward a distant goal, Arendt added, new opponents or enemies are repeatedly invoked; “as soon as one category is liquidated, war may be declared on another.”

Another trait of totalitarian governments, Arendt observed, is a perverse disdain for both “common sense and self-interest”: a stance fueled by mendacity and denial of facts and embraced by megalomaniacal leaders, eager to believe that failures can be denied or erased and “mad enough to discard all limited and local interests—economic, national, human, military—in favor of a purely fictitious reality” that endows them with infallibility and absolute power.

The Origins of Totalitarianism is essential reading not only because it reminds us of the monstrous crimes committed by Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union in the twentieth century but also because it provides a chilling warning of the dynamics that could fuel totalitarian movements in the future. The book underscores how alienation, rootlessness, and economic uncertainty can make people susceptible to the lies and conspiracy theories dispensed by tyrants. It shows how the weaponization of bigotry and racism by demagogues fuels populist movements built upon tribal hatreds while undermining the longstanding institutions meant to protect our freedoms and the rule of law and shattering the very idea of a shared sense of humanity.

__________________________________

Adapted excerpt from Ex Libris by Michiko Kakutani, copyright © 2020 by Michiko Kakutani. Used by permission of Clarkson Potter, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Michiko Kakutani

Michiko Kakutani, the former chief book critic of The New York Times, is the author of the 2018 bestseller The Death of Truth: Notes on Falsehood in the Age of Trump.