Michelle Tea on Undertaking the Wild Art Project of Motherhood

“It seemed like having a kid was the only adventure I hadn’t undertaken.”

When I started telling the people around me that I was going to get myself pregnant, they reacted in a variety of ways, and not always as expected. My two best friends, with whom I have a very codefriendent relationship, were skeptical. “You can’t just go and put the baby in the other room when you want to have sex,” Tali said wryly, an apparent comment on my amorous lifestyle.

Tali and I have been friends since the nineties, when we were both drunken poets slurring into the mic at open-mic events. Now that we were older, and sober, Tali’s approach to life had become more grounded and cautious, and she was unafraid to offer her strong opinions, peppered as they were with a dark and honest humor.

I was uncertain how to respond to my dear friend’s read—of course I understood that the baby would have to come before my libido, but, really, why couldn’t I tuck the baby in the other room when I wanted to have sex? That sounded reasonable. Tali tried another angle: “You like to take off and go to Paris.” I was becoming a bit enchanted with my life as seen through my friend’s eyes. Who was this jet-setting tart?

But I hadn’t been to Paris in years, and anyway, wouldn’t I want to take my little bohemian baby traveling abroad? Wouldn’t I want to teach them French by immersion in the cafés of the Bastille? In fact, maybe I would want to actually give birth in Paris, gifting my bébé with dual citizenship in an elegant, socialist country and treating myself to a free, socialist hospital birth! Tali saw that her warnings were having the opposite effect and sighed in resignation, offering one more deterrent: “But you love your life.”

This made me pause: I do love my life, I thought to myself. I lived by myself in a spacious San Francisco apartment I could miraculously afford with the income I patched together running a literary nonprofit, writing books and essays, and reading tarot cards. My apartment building was old and gray, but in a dignified way, like Iris Apfel. The staircase had a polished wood banister, and the lobby was lined with mirrors, so you could get your Last Lewks in before you pushed open the heavy glass door and went out onto the wind tunnel that is Page Street.

Everyone, it seemed, had stories of miserable single mothers and they all wanted to share them with me.

Landing there seemed like a miracle in and of itself; not least because my inbred money scarcity almost pushed me to turn my back on it. The fact that the rent was seriously under market value—this, during the legendary San Francisco era of the Tech Bro!—did not even register to me.

All I saw was that it was more money than I’d ever spent on housing, and I balked, fear of having to come up with more money per month setting my stomach churning. Thankfully, some friends who, while they may be similarly blinded by their own survival fears, can at least see it plain and clear when manifesting in another. “That entire apartment literally costs two hundred dollars more a month than what you’re paying to live in a converted living room in a flat with twentysomethings who keep mistaking their cocaine panic for heart attacks and calling the fire department,” Tali lectured sternly. “You should move.”

San Francisco is a city of neighborhoods, but this latest spot I found myself in, my charmed apartment, seemed to be in a liminal space. I’d lived in a few different San Francisco neighborhoods—mostly the Mission, which I watched go from a neighborhood of Latinx families, Salvadoran restaurants, street hookers, and dykes to a neighborhood of white tech workers, pastry shops selling deconstructed confections, electric scooters, and yoga moms.

For years I lived in North Beach, worried the throngs of tourists would drive me mad, but I was ultimately delighted to be residing in a spot that so many people, from all around the world, wanted to visit. The air smelled like rosemary focaccia, and my local bookstore was City Lights, where the elderly Lawrence Ferlinghetti (RIP) was often in residence, being interviewed by European film crews.

I’d also lived in Bernal Heights, both at the foggy top of the hill, where condensation would drift beneath the back door and fill the kitchen with clouds, and at the bottom, where the jagged singsong of drunkards doing karaoke at Nap’s provided a quirky soundtrack to my life. My new neighborhood was a no-man’s-land that wasn’t quite the grungy Lower Haight and wasn’t quite Hayes Valley. It was a lovely spot that allowed me to walk most anywhere, or hop on a lumbering orange bus if it was rainy or I was lazy.

After decades cohabiting with various roommates, I relished the luxury of my own apartment. Nobody left passive-aggressive notes for me if I didn’t clean up my mess swiftly enough. No having to nag people for their portion of the electric bill. No facing another human in the kitchen before I’d had my first cup of coffee.

Throughout my twenties, I thought of pregnancy the same way I thought of any STD, but with a dose of the movie Alien.

Life was pretty blissful, and when I thought about my humble beginnings, across the country in a run-down New England town, my life felt like a freaking fairy tale. Which was exactly why I wanted to bring a little creature into it! From where I stood, deep into my fortieth year on earth, my remaining eggs hobbling down my fallopian tubes each month, tennis balls wedged onto their walkers, it seemed like having a kid was the only adventure I hadn’t undertaken.

My friend Mel’s face crumpled in despair when I told them. “Your work!” they moaned, mourning all the books I would not write. They told me all about the depressing life of their girlfriend’s sister, a single mother. Everyone, it seemed, had stories of miserable single mothers and they all wanted to share them with me.

And yet all the moms I knew were totally psyched and encouraging of my steps toward Babyville. My AA sponsor, deeply in love with her adopted son, urged me on, suggesting I have an affair while traveling.

In their thirties, while selling weed, my friend Belle accidentally got knocked up by their bipolar boyfriend and kept the baby; now they have a second kid and live an inspiring life in Hollywood working on television projects (sans bipolar boyfriend). They racked their brain for sperm donors, briefly offering up their husband, but then realized they’d be upset if my baby wound up better than theirs.

Esther, another writer who kept her accidental pregnancy, also thought it was a great idea. We remembered sitting backstage with Exene Cervenka at a poetry reading, how she urged us to have a kid someday. “It makes you more psychic,” she promised, a nice perk.

My sister Madeline, who not only had a three-year-old daughter but who knows me better than anyone—my strengths and weaknesses, how I am both diligent and a space cadet—began teaching me how to track my ovulation cycle. My mother, a lovable nervous wreck who is often frightened of my life choices (sex work, walking through the East Village alone past midnight, attending Mayan sweat lodges in the Mexican jungle), surprised me by offering advice on turkey basters. How did she know about this classic, lesbian method of insemination?

Floating on their encouragement, it seemed that I was—with a lingering hint of trepidation—really pursuing this! With my mom on board, how could even my most reticent friends not come around? Tali, who supports her writing habit by working in a co-op grocery store, relented: “Well, I can get you twenty percent off your prenatal vitamins. And tell your mom we have really high-quality glass turkey basters.”

Ariel’s book was the first thing I had ever read that gave me—poor, queer, weird—permission to bring a kid into the world.

Although my friends’ anti-baby fears gave me the opportunity to try out my pro-baby arguments, the truth was, the dare to depart in this wild new direction existed inside my body alongside self-doubt, the economic scarcity issues that were my birthright, and basic terror of the unknown. My inner Yes and No merged into a gray fog of ambivalence. I wanted to know, with a bright, clear one hundred percent assurance that Yes, a child was totally my destiny and would make my life complete, or No, I was simply not cut out for motherhood, what with my head for art and my bod for sin and my income that fluctuated like a PMS mood swing.

Throughout my twenties, I thought of pregnancy the same way I thought of any STD, but with a dose of the movie Alien. Something foreign gestates inside you, siphoning your nutrients, changing your behaviors (as many parasites do), before finally clawing its way out, leaving you maimed and possibly even dead. Many acquaintances were disturbed by this understanding of babies as invasive monsters and not, you know, cute.

Then, at twenty-seven, I read Ariel Gore’s book The Hip Mama Survival Guide and suddenly pregnancy seemed sort of cool, like some sort of wild art project. Ariel’s book was the first thing I had ever read that gave me—poor, queer, weird—permission to bring a kid into the world. I don’t know if the book triggered something biological or if it was right time, right place, but suddenly babies didn’t seem like the grotesque hobgoblins I’d feared them to be. In fact, I began craving the feeling of being pregnant. What is this? I marveled. How could my body crave something it had never known? This new sensation surged briefly into an obsession before it receded, leaving me different. The thought of having a kid was no longer repulsive.

For the next decade, I wobbled back and forth, wondering if a child was something I wanted. It was frustrating not to know. I had a long-term relationship with someone who absolutely did not want a baby, who got worked into a frenzy if the topic was introduced even speculatively, causing me to shelve it. Later, I dated people who did want children, but they tended to suffer from borderline personality disorder or some Not Otherwise Specified psychological malaise.

How could my body crave something it had never known? This new sensation surged briefly into an obsession before it receded, leaving me different.

It seemed that if I had a healthy partner who wanted a baby, then maybe I would want a baby, too. I began to lament the impossibility of getting accidentally knocked up. When I was younger, I was relieved that the people I dated—women, trans men, and gender nonconforming people assigned female at birth— could not get me pregnant. What a great thing not to have to worry about. Now I was regretful that I couldn’t allow a broken condom to make the decision for me.

All of this brings me to a cold summer night in San Francisco, when I sat at my vintage kitchen table, a cheery, buttercup-yellow Formica, my laptop displaying what appeared to be a legit source detailing how tragic my forty-year-old eggs were. Horrifyingly, I learned, your eggs are best during the fragile era of your late teens/ early twenties. By the time you’re forty, you are 46 percent likely not to get pregnant; in just five years that rises to 58 percent. If I wanted a baby, I would have to do it right then. Like, right that very second.

But I wasn’t in a real relationship! I had allowed a somewhat recent heartbreak to slingshot me into a rebound with a person who was likewise rebounding from their own heartbreak. This fake relationship provided us both with an excellent diversion from the fact that we were sort of still in love with our respective exes. We wrote poetry together, attended the county fair, arrived at avant-garde art events arm in arm, and spent our workdays contributing to an excitingly perverse G-Chat thread set in the broom closet of a Catholic high school, featuring a janitor and moi. We even spoke wistfully about running away to New York City to start an art gallery, or to Amsterdam to be hookers. But despite the idyllic picture I’m painting, our connection was marred by the simple fact that our hearts were elsewhere.

There, at my kitchen table in the June of my fortieth year, the mandate seemed clear: get out of my fake relationship, find someone hot and not insane who wanted to have a baby ASAP, and get to bonding on the double so that we’d be ready to take this life-changing step together by the end of the year.

And so, I began to cry. But the crying, I shortly realized, was good! The crying was very good! I was finally having a definite feeling about having a kid! Look how inconsolable I got when it seemed I couldn’t have one! I did want one! I clicked shut my computer, flipped a tarot card, and regarded the High Priestess and all her introspective self-knowing, her solitary femme power and overall positive vibes. I broke up with my fake date. And I decided to have a baby.

________________________________

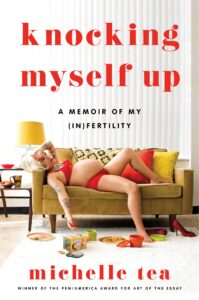

From Knocking Myself Up by Michelle Tea, available from Dey Street Books

Michelle Tea

Michelle Tea is the author of over a dozen books, including Modern Tarot, Knocking Myself Up, and Against Memoir. She is the founder and former executive director of the literary nonprofit RADAR Productions, where she pioneered the first Drag Queen Story Hour. Valencia received the Lambda Literary Award for Best Lesbian Fiction and was adapted into a feature film.