Visiting Mariah Carey’s Cat’s Grave: Reflections on Disenfranchised Grief

E.B. Bartels on the Particular Sorrow of Losing a Pet

The grave I was looking for was in a quiet back corner of the cemetery, surrounded by trees. I was grateful for the shade—it was August in Westchester County, and the place was hot. Asphalt pathways criss-crossed rows of blinding granite headstones; my black dress clung to the sweat on my back. I’d spent the afternoon walking up and down the paths of this four-acre cemetery. Bright spots of metallic pinwheels, Mylar balloons, and neon stuffed animals decorated the headstones. Flowers wilted in the summer sun.

Under the trees, weaving through the graves, I found the marker: pink granite, engraved with hearts. Clarence, it read. My eternal friend and Guardian angel. You’ll always be a part of me forever. And underneath, obscured by flowers: love, M.

I had read about Clarence. I knew he was a loyal friend, kind, affectionate, sweet. Even though he ran with a famous crowd, he didn’t seem to care about money or celebrity or power. He valued the simple things in life. I studied the dates under Clarence’s name: 1979–1997. Clarence was eighteen when he died— by most cemeteries’ standards, painfully young. But in this cemetery, in Hartsdale, New York, eighteen is a good, long life.

I was looking at the grave of Mariah Carey’s cat.

When we open our hearts to animals, death is the inevitable price.This was not my first celebrity pet memorial. I’ve sat at the grave of Donald Stuart, Royal Nelson, and Laddie Miller—Lizzie Borden’s Boston terriers—their headstone engraved with the phrase sleeping awhile. I visited Pet Memorial Park, in Calabasas, California, where Hopalong Cassidy’s horse, Rudolph Valentino’s and Humphrey Bogart’s dogs, Charlie Chaplin’s cat, and one of the MGM lions are buried.

I traveled to the outskirts of Paris to see Rin Tin Tin’s grave in the Cimetière des Chiens et Autres Animaux Domestiques. I’ve said a prayer standing over the final resting place of America’s hero racehorse Secretariat, in Lexington, Kentucky. But every time, what impressed me more than the celebrity pet graves was all the headstones that surrounded them.

Celebrities are not alone in burying their dead pets. To the left and right of Clarence’s pink granite tombstone were hundreds of graves for other animals belonging to regular people. These memorials were no more or less lavish than the headstone Mariah had engraved for Clarence. If I hadn’t known about the telltale love, M on Clarence’s stone, I wouldn’t have been able to distinguish his grave from any of the others. Celebrities, I thought, studying the two hearts flanking Clarence’s name. They’re just like us.

By the time I visited Hartsdale, I’d already had a long personal history with pet cemeteries; in fact, I went to high school next to one. My school was of the New England prep variety, with facilities better than those at many colleges, on a gorgeous green campus in Dedham, a suburb southwest of Boston. This was the sort of school that carefully curated its image, boasting of athletic alumni competing in the Olympics, generations of legacy students, high SAT scores, and extremely competitive Ivy League acceptance rates. Less present in its marketing materials: that the school is located next to several thousand dead animals, buried in the Animal Rescue League of Boston’s Pine Ridge Pet Cemetery. Pine Ridge was the first official pet cemetery I knew of, but there are more than seven hundred of them scattered throughout the country.

By the time I was fourteen and first saw Pine Ridge, I’d already loved and lost many companion animals. I also loved to read, and, frankly, young adult literature is full of dead pets. “I remember that awful dread as the number of pages shrank in each new animal book I read,” writes Helen Macdonald in her memoir H Is for Hawk. “I knew what would happen. And it happened every time.” What happens in Old Yeller? The dog dies. In Where the Red Fern Grows? Two dogs die. The Red Pony? The pony dies. Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing? The turtle dies.

In this way, grieving pets is a disenfranchised grief, which can make it hard to know how to process and honor it.I could go on.

When we open our hearts to animals, death is the inevitable price. Jake Maynard, in his essay “Rattled: The Recklessness of Loving a Dog,” writes that loving an animal is “mortgaging future heartbreak against a decade or so of camaraderie.” Matthew Gilbert, in his memoir Off the Leash: A Year at the Dog Park, writes, “In the course of an average human lifetime, pots and pans and couches and lamps stay with us for longer stretches of time. Even beloved T-shirts survive the decades, the silk-screened album images and tour dates wrinkled and cracked but still holding on. With a dog, you’re on a fast train to heartache.”

Yet people keep getting pets. As of the writing of this, 67 percent of American households, 84.9 million homes, own “some sort of pet,” according to the American Pet Products Association. And yet, despite those millions of pet owners all over the globe, and despite the inevitable loss that comes with that relationship, the ways people grieve a dead pet aren’t always taken very seriously.

Imagine Mariah canceling a world tour due to “a death in the family.” If her mother died, of course people would understand, without question. She would get cards and flowers; fans would send encouraging, sympathetic messages. But if Mariah put off a tour to mourn for her cat Clarence? Some fans would get it, I’m sure, but she would also certainly become the butt of thousands of jokes on social media.

For every pet that’s died, the one thing they’ve had in common has been my feeling of not knowing what to do with my grief—I could do everything, anything, nothing.Fiona Apple actually did postpone her South American tour in 2012 to spend more time with her dying pit bull, Janet, publishing a handwritten note explaining her reasoning to fans on her Facebook page. (Apple would later play percussion using Janet’s bones in a song on her album Fetch the Bolt Cutters.) Thousands of fans wrote supportive messages—it seems on brand that Fiona Apple fans would get it—but there were also ugly comments the moderators had to delete. Pets don’t live very long. They’re going to die. What were you expecting? Taking time off from work to grieve for your pet as you would for a human—some say that’s too much.

In this way, grieving pets is a disenfranchised grief, which can make it hard to know how to process and honor it; but there’s freedom in that, too. With social acceptance come social standards and expectations. The human funerals I’ve been to run together in my mind.

I grew up in an Italian Irish Catholic household in Massachusetts, so to me the death of a person meant the same open casket, the same Bible verses, the same laminated prayer cards and stiff black clothes, the same taste of funeral home Life Savers, the overpowering scent of day lilies, the post-funeral deli sandwiches. Different cultures have different traditions, but every culture typically does have its own set of mourning rituals—for humans. The rituals may feel tedious and repetitive at times, but they also offer stability and closure. There is comfort in the expectedness. Even in the “spiritual not religious” memorial services I’ve been to, I see patterns: the same large-format photos of the deceased, the same Dylan Thomas poem, the same covers of “Make You Feel My Love.”

There’s no guidebook for mourning your animal. Some people keep urns with their animals’ ashes on their mantels for decades; others bury their pets (sometimes illegally) in their yards. Some knit scarves out of their cats’ fur; others have their dogs taxidermied. Some immediately go out and get a new puppy or kitten; others vow never to love again.

Taking time off from work to grieve for your pet as you would for a human—some say that’s too much.When your pet dies, it’s possible you’ve never seen anyone else grieve for a pet. There’s a good chance you won’t have a model to follow. My family cremated one of our dogs and spread his ashes by a lighthouse; another I carried home from the vet wrapped in towels, and we buried her in our yard. I made a small cemetery behind my childhood home to entomb my birds and fish; we never acknowledged the inevitable death of the tortoise that went missing.

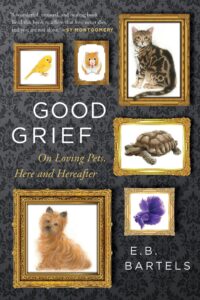

For every pet that’s died, the one thing they’ve had in common has been my feeling of not knowing what to do with my grief—I could do everything, anything, nothing. I often wished for an encyclopedia of options, a guidebook to help me figure out how best to honor my departed animal friends, to both grieve for and celebrate their lives. I want my book, Good Grief, to be that guide.

That August day in Hartsdale, it struck me that every animal was buried there intentionally. No pet is buried in a cemetery because the law requires it; pets are buried in a cemetery because a human wanted them to be there. It doesn’t matter if it is the Jindaiji Pet Cemetery, in Tokyo, or Pet Heaven Memorial Park, in Miami—worldwide, throughout history, the love is the same, and the people who honor their pets in this way understand one another.

As I sat by Clarence’s memorial, I watched a woman visit her pet’s grave. She borrowed scissors from the cemetery office to trim back the grass around the stone. A few rows over, a man carried a bouquet of flowers. He approached the woman to borrow the scissors; she gave them to him with a nod. No judgment in the exchange, just one pet person to another. When you get it, you get it.

_________________________________

From Good Grief: On Loving Pets, Here and Hereafter by E.B. Bartels, available from Mariner