At the Musée de l’Homme, the Magdalenian III-era engraving in stone representing a woman (obese, we think) whose fringed garment seems to have been reproduced with great accuracy.

In Crete—where I have never been—the fresco, so contemporary despite its antiquity, named “The Parisians.”

In Sicily, the women in bikinis appearing in a Roman mosaic in the Piazza Armerina.

At the Accademia in Venice, in the background of one of Carpaccio’s paintings depicting scenes from the life of Saint Ursula—specifically, the arrival of English ambassadors in Brittany—the dogs walking around a square full of people whom the artist unquestionably wanted dressed in the latest fashions of the day, from the young dandies up to (what appears to be) a dwarf as fat as a Buddha; then—in The Dream of St. Ursula, a later episode—the fine pair of slippers neatly arranged at the foot of the bed of the sleeping saint.

Turner’s famous painting (Rain, Steam, and Speed in the National Gallery) depicting the blackness of a locomotive amidst a luminous brew of color, hence contrasting with and emerging from chaos.

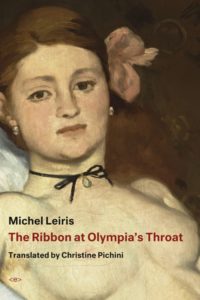

The ribbon tied around the neck of Manet’s Olympia and the mules that her feet, as explicitly naked as her entire body appears to be as a result of the addition of those accessories, seem ready to lose.

The watch-bracelets that, encircling their wrists, prevent many of the innumerable nudes whom Picasso sketched or painted from becoming mythological Venuses.

The hypodermic needle that Bacon planted in the arm of a female nude that, by modernizing her, renders the figure more authentically present.

The pretty little slipper that reveals Perrault’s Cinderella, the Cinderella of Christmas pantomime plays, and—when transformed into a bracelet—Rossini’s Cenerentola.

The detail we touch with our fingers, bait we sink our teeth into, that makes Saint Thomases of us.

In the theatre, the powdered skull, the walking statue, the razor, the fool’s marotte, the white uniform, the severed head on a platter, etc., that conjure up ghosts for Hamlet, Don Juan, Figaro, Rigoletto, l’Aiglon, Salomé and others.

The stocking that the girl of yesteryear kept on to prevent herself from dissolving into the edenic blur of total nudity.

The detail we touch with our fingers, bait we sink our teeth into, that makes Saint Thomases of us.

Expected or unexpected, the moment that exposes and disarms the sinister passage of time.

*

My father gave me

Rubies, rubettes, My

father gave me

Ribbons of satin. . .

Refrain that returns to me from childhood, sung quietly by a woman or a little girl. On the way, it has become coated with a melancholic sheen.

*

In Paris, 1959, in the expressly cultural setting of the Théatre de Nations, which produced a variety of performances every year that eventually came from very far away and were sometimes extremely beautiful, the Frankfurt Opera presented, under the musical direction of Georg Solti, The Marriage of Figaro. A connoisseur who was even the slightest bit particular would have been put off by the fact that this work by Mozart and da Ponte was sung in German and not Italian, but this didn’t prevent me, more gourmand than gourmet in many respects, from being enraptured by the evening.

At the end of the “Air militaire” with which the first act draws to a close (that famous air that Mozart recovers as a quotation in one of Don Juan’s final scenes, as if to infuse the sacrilegious feast with a bit of mischief and perhaps, on a deeper level, as if this anachronistic reminder, an irruption of the now within a legendary tragedy, indicates that we are already living outside of time at the moment when, with the walking statue, the supernatural makes its radiant entrance) we witness Chérubin—a graceful cantatrice, as vocally effortless as she is convincing in her spirited performance of a libertine in training—throw from the back of the stage, and with enough force that the projectile passes above the heads of the musicians assembled in their pit, the hat (in this instance a tricorne) that is no longer suitable now that, in order that he be sent away, Chérubin has been elevated from the rank of page to officer. With his left hand, the maestro Solti catches the object in flight, while he continues to conduct with his right hand holding the baton for the several remaining measures.

Apparently improvised, this gag had two virtues at the very least: in a single gesture, it eliminated any and all of the distance that is almost always too rigidly divided in our theaters between set and orchestra, as well as between stage and audience, and its casualness demonstrated an easygoing intimacy with the masterpiece that is all too frequently performed with a seriousness that borders on pedantry. An impulsive conclusion of a brilliant performance, it seemed to respond spontaneously to the idea that if you wish to do something extraordinary, you must leave a bit of space for the living and unforeseen reality of the happening, even in a performance whose progression is very classically regulated.

Nevertheless, I must say that before it inspired this theoretical reflection concerning the art of performance, the prank charmed me and made me immediately think (the action’s implied location no doubt helped in this) of the brazen authority that, if it comes at the proper moment, may be produced by what the language of bullfighting calls an adorno, and in which, without any ham-handed showing off, the toreador inserts an addendum into a magisterial labor with no other goal than to demonstrate the extent to which he dominates the animal he is fighting.

But perhaps this is a fortuitous analogy, resting on another marginal detail that made me skid off from opera’s prestiges to those of the bullring. Chérubin’s gesture, creating a bridge between fiction and reality by making his tricorne soar above the orchestra and its rows of music stands, actually reminded me, if not in spirit at least in form, of the matador’s gesture of throwing the montera that he had been wearing to the man or woman to whom, on the other side of the circular corridor where minions such as matadors’ assistants sit, he dedicates the toro he is readying himself to kill.

*

In front of Regan, whom we will soon see voluptuously snaking her gorgeous arms, the Duke of Cornwall gouges out the eye of the elderly Count of Gloucester, tied to the stake. A sudden blackout, both on stage and in the hall, and for a moment it is pitch dark. Same trick for the second eye, and again the spectator has the cruel, abrupt sensation of having suddenly become blind himself.

In this way, the paroxysmal form of theater described by Antonin Artaud unexpectedly took shape in an English production of King Lear, whose staging was flatly historical and entirely banal from beginning to end.

*

By the bed where Desdemona has just been put to death by her husband—in whom Iago planted the idea that the young noblewoman who had scandalously run off with him, a man of another class and another race, was bound to betray him sooner or later—a high-backed chair. Very tall and very strong, the tenor playing Othello that night at the Paris Opera (I could give you the precise date, but to do so I would have to scavenge through the messy cabinet holding my personal archives in order to find the program that I kept, as I do for almost all of the performances I attend unless they were only mildly interesting, work which would hardly be proportionate to the minor importance of that chronological detail), the Wagnerian tenor Hans Beirer, whom I had already heard and appreciated in other roles, presses his two hands on the back of the chair. The chair collapses under his weight and, for a moment, Othello seems about to fall. But the singer corrects himself and the incident that, if a fall had occurred, would have unexpectedly thrown the drama into the tall grass of the burlesque proves, on the contrary, to be a happy accident. No calculated stage direction could have illustrated the Moor’s Herculean strength and his bewildered state in a more convincing way.

*

Achilles, wearing a woman’s dress, now wails before Patrocles’ outstretched corpse, nearly naked and bleeding at his feet. He neither recites nor, suffice it to say, acts, but as he stands facing the audience he howls, moans, lows, brays, and trumpets, and this outburst pierces a hole in the heart of the tragedy. With his bestial cry, the actor suddenly makes himself so present—separated from us by as few screens as he is from his character—that it’s almost disturbing. Is it not reality itself that obscenely erupts, in all its terrible rawness? No longer Alan Howard, playing one of the main roles in Troilus and Cressida, but Achilles himself, the wrecked and furious lover who with his delirious clamor punctures the poetic fabric of which the Trojan War is the thread and, leaving the cloud of the legend behind, appears right in front of us to give voice to our unfathomable wound.

*

In the second act of The Tragedy of King Christophe, the play in which Aimé Césaire made a hero of Shakespearean proportions out of a former slave who became king, one character makes an appearance in only one short scene: after being sent by Louis XVIII to invite Christophe, who reigns over the north of Haiti, to return to the heart of France, the Spanish Franco de Medina provokes the anger of the monarch, who then condemns him to death. We see him walk towards the execution site, escorted by several soldiers. The role is limited to an entrance, a couple of brief ripostes, and an exit—a shallow role, and entirely incidental, a “nothing” part that is difficult to imagine any actor making memorable. And nothing is what, until this production (one of the ones that were staged in Dakar in 1965), those who were responsible for it ever made of it, however hard they may have tried!

But, as luck would have it, Jean-Marie Serreau, the producer and director of the troupe, was forced to play the role at the last minute to replace the incumbent at the time, who had been called to Paris on some kind of business. Neither Césaire nor any of his friends who like myself were in the audience were aware of this replacement. Great, then, was our surprise when this new Franco of Medina appeared onstage and we saw this paltry character suddenly become something more than the bland silhouette to which we were accustomed.

Two ideas as simple as ABC. Historically, Franco de Medina was a Spaniard and so it goes without saying that his French pronunciation suffered for it—a chance for Serreau to give the character some caricaturish vigor by endowing him with a thick accent. Theatrically, his exit posed a problem: how should he walk away to die? An afflicted pace would have been too melodramatic and a martial one too “patriotic,” so the role’s interpreters had until then prudently abstained from any psychological indication, which brought the scene to an abrupt end. But Serreau knew how to handle the situation by adding a visible limp to the burlesque accent of his Franco de Medina, a double blow since, on the one hand, he individualized it even more by making the character lame and, on the other, conferred upon Franco an immediate theatrical interest by having him walk to his death while pitifully dragging his leg, perhaps as gouty as his royal patron.

I’ve always admired that an actor was able, through his ingenuity, to give substance to a role that Césaire had only introduced into his play to emphasize one side of Christophe’s character. Serreau took hold of the various givens and resolved the problem with brio: a man of the theatre who yielded to the exigencies of the performance but remained scrupulous enough to satisfy them without becoming gratuitous. Thus fantasy, united with authenticity, led to the absolute presence of a figure who formerly did not exist.

*

The nail clipping, lock of hair or other fragment of a body through which magic may be practiced.

In the work of Sigmund Freud, whom a French intellectual in the ’20s compared to a detective (namely, Nick Carter) whose mystery pursuits were based on infinitesimal clues, the slight thing—slip, memory lapse. . .—filled with great significance.

In the work of Marcel Proust, who spent practically all of his time trying to neutralize time, the fugitive sensation that causes a broad swath of memory to resurface.

Newton’s apple, the precise and concrete case from which one begins to elaborate a theory.

On the contrary, the drop of water that makes the vessel overflow.

__________________________________

From The Ribbon at Olympia’s Throat by Michel Leiris, trans. by Christine Pichini. Used with permission of Semiotext(e).

Michel Leiris

Michel Leiris (1901–1990) was a French surrealist writer and ethnographer. Part of the Surrealist group in Paris, Leiris became a key member of the College of Sociology with Georges Bataille and head of research in ethnography at the CNRS.