Mental Illness is Not a Capital Crime

On the Disproportionate Impact of Police Violence on Women of Color

Two and a half decades after the 1991 beating of Rodney King was broadcast on TV, another bystander captured video of a different beating by the side of a Los Angeles freeway, featuring another Black grandmother. Marlene Pinnock, diagnosed as bipolar, had been homeless off and on for several years. She was walking along Interstate 10 in Los Angeles, headed to a location where she felt safe to sleep that was only accessible by freeway. A California Highway Patrol officer stopped her, eventually tackled and threw her to the ground, and proceeded to punch her in the head ten times as he straddled her body on the side of the freeway. Marlene later said, “He grabbed me, he threw me down, he started beating me. . . I felt like he was trying to kill me, beat me to death.” Adding insult to injury, during the assault Marlene’s skirt began to ride up. When she attempted to pull it down, the officer ripped her dress, displaying her naked buttocks to surrounding traffic. She was subsequently hospitalized for several weeks for injuries to her head, which left her with slurred speech, and experienced ongoing nightmares about the incident. The officer also claimed that Marlene was mentally unstable, causing the hospital to hold her longer, against her will, for observation.

The officer later claimed that he stopped Marlene because she was walking barefoot on a highway talking to herself, presenting a danger to herself and motorists, and that she told him she wanted to walk home and called him “the devil.” He also claimed that she was resisting arrest. The man who captured the beating on video told Reverend Al Sharpton that after the officer first approached her, Marlene walked away, off the highway. The officer re-engaged her and escalated the situation; the witness observed no resistance whatsoever. Once the video went viral, civil rights leaders began to speak out about Marlene’s beating, using the video to counter the officer’s justifications for the violence. “Without the video my word may have not meant anything,” Marlene said.

The Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office investigated the incident and concluded that the officer’s “use of force was legal and necessary.” The report quotes officers describing Marlene as “strong”—again invoking racially gendered narratives of Black women with superhuman strength, immune to pain. The officer admitted that he donned gloves before taking her down because she was homeless, and that he was “fucking wailing [sic] away” on her. Highlighting the role of public perceptions of Black women in fueling police violence, the report also documented statements by individuals who reported Marlene’s presence on the freeway to police based on assumptions that Marlene might have a gun or pose a threat, and which describe her as “looking psycho.” A civil suit resulted in a $1.5 million settlement, and the officer responsible agreed to resign from the force.

*

On October 18, 2016, things came back full circle when, 32 years after the killing of Eleanor Bumpurs, history repeated itself. NYPD officers, responding to a call about an “emotionally disturbed person,” shot to death 66-year-old Deborah Danner, who had been diagnosed as schizophrenic, in her Bronx apartment. Police claimed that Danner had advanced on them with a baseball bat. The connection to the Bumpurs case was quickly made by protesters and media—and, most strikingly, by Danner herself, who wrote about deadly police responses to people labeled with mental illness four years before she was killed: “We are all aware of the all too frequent news stories of the mentally ill who come up against law enforcement instead of mental health professionals and end up dead. . . They used deadly force to subdue her [Bumpurs] because they were not trained sufficiently in how to engage the mentally ill in crisis. This was not an isolated incident.” City officials quickly admitted that, in Danner’s case, responding officers had not followed NYPD policies governing responses to calls about people in mental health crisis, which had been changed following Bumpurs’s killing.

At least half a dozen cases of police shootings of Black women documented in Say Her Name, the report I coauthored with Kimberlé Crenshaw, arose from police interactions with women in actual or perceived mental health crisis: Shereese Francis, killed in New York City in March 2012; Miriam Carey, shot in Washington, DC, in October 2013; Pearlie Golden, shot in Hearne, Texas, in May 2014; Tanisha Anderson, killed in Cleveland in November 2014. Although no official statistics exist, based on my experience tracking cases over the years, it appears that police responses to mental health crises make up a significant proportion of Black women and women of color’s lethal encounters with police. As was the case for Eleanor and Deborah, these encounters often reflect police perceptions of Black women as volatile and violent, portrayed, in the words of historian Sarah Haley, as “daft,” “imbecilic,” “monstrous,” “deranged subjects,” “lacking essential traits of personhood and normative femininity,” to be met with deadly force rather than compassion, no matter their condition or circumstance.

Indeed, disability—both mental and physical—is socially constructed in ways comparable to, and mutually constitutive of, the construction of race and gender. As disability justice and transformative justice activist Mia Mingus points out, women of color are already understood as “mentally unstable,” regardless of whether or not they are actually “disabled.” “This kind of racialized able-ism inherently informs how police (and society at large) interact with Black and Indigenous women, and women of color.” Actual or perceived disability, including mental illness, has thus served as a primary driver of surveillance, policing, and punishment for women and gender-nonconforming people of color throughout US history.

Scientific racism has been fundamental to conceptions of mental health and disorder. According to Vanessa Jackson, the first asylums for “lunatic slaves” were created in response to a case of a Black woman found to be insane after she allegedly killed her child. Indeed, resistance to slavery was pathologized as mental illness inherent in African-descended people. The same resistance-equals-insanity trope was projected onto Indigenous people. In her pamphlet Wild Indians, Pemina Yellow Bird, a member of the Three Affiliated Tribes and psychiatric survivor activist, describes how, from 1899 to 1933, Indigenous people who resisted reservation agents, refused kidnapping of their children to Indian Residential Schools, or violated laws that criminalized traditional spiritual practices were sent to the Hiawatha Asylum for Insane Indians in Canton, South Dakota. There, “Indian defectives” were incarcerated and subjected to torture and physical, cultural, and spiritual abuses.

Urban policing also evolved in part around a mandate to remove both gender-transgressing and disabled bodies from public spaces. According to Clare Sears, “Within 19th-century municipal code books, for example, cross-dressing, prostitute, and disabled bodies appeared alongside one another as (il)legal equivalents in public space, through general orders that banned the public appearance of a person wearing ‘a dress not belonging to his or her sex,’ in ‘a state of nudity,’ or ‘deformed so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object.’” As a result, in the first half of the 20th century, disabled women—as well as lesbian, bisexual, and transgender women labeled as having a psychiatric disability because of their sexual or gender nonconformity—were forced into institutions, often following interactions with law enforcement.

Today police continue to target people who have, or who they perceive to have, psychiatric or cognitive disabilities for violence, arrest, and commitment in institutions of various kinds. National statistics indicate that the majority of people who experience police violence are labeled as mentally or physically disabled; one study estimates that “roughly a third to a half of all people killed by police are disabled” and that the “most common type of killing” involves a person who is in “a mental health crisis” and is holding an item described as a weapon (from firearms to household implements or tools) when shot by law enforcement. According to the Treatment Advocacy Center, “The risk of being killed during a police incident is 16 times greater for individuals with untreated mental illness than for other civilians approached or stopped by officers.”

The risk of deadly police encounters for people labeled mentally ill has increased significantly since the 1970s in the wake of deinstitutionalization. A severe shortage of community-based services has produced disproportionate levels of homelessness and unemployment among people with mental illness and other disabilities, resulting in increased police contact in the context of the criminalization of poverty in public spaces, housing, and services. Additionally, in the absence of alternatives, the police tend to be the people called to assist people in the midst of a mental health crisis; in New York City, for example, the police department receives approximately 400 mental health-related calls a day. Arrest rates among recipients of public mental health services are four and a half times those in the general population; most of these arrests are for “public nuisance” offenses. Officers exercise significant discretion when determining whether to respond to calls involving people in mental health crisis with violence, arrest, involuntary commitment, or nonpunitive responses. Arrests are more likely when individuals are perceived as “disrespectful” or use offensive language, especially in public situations.

Not surprisingly, race and gender continue to frame perceptions of disability and police responses. Police are more likely to criminalize and use excessive force against people of color with psychiatric disabilities through a process that law professor Camille A. Nelson terms the “disabling of race and the racing of disability.” Nelson described the case of Rosie Banks, a 13-year-old autistic junior high student who reacted to teasing by fellow students in “an aggressive manner.” When brought to the administrative office, an officer who “just happened to be there,” immediately confronted her. When she became “more aggressive,” he pepper-sprayed her in the face. In so doing, and in a subsequent incident in which he handcuffed Rosie, the officer immediately circumvented de-escalation options typically used with white students, even when they pose a greater objective threat. Nelson posits that race, gender, and disability all played mutually reinforcing roles in this exercise of discretion. Rosie Banks’s treatment was no doubt also informed by her failure to display the passivity expected of people with disabilities.

The odds that Black women and women of color who are or are perceived to be in mental health crisis will experience violence, arrest, or involuntary commitment are compounded by perceptions of mental instability based on gender, gender nonconformity, and sexuality. Trans people and gender-nonconforming people have long been treated by medical professionals and law enforcement as mentally unstable, leading police to respond based on presumptions of volatility and irrationality that must be subdued with force.

For Kayla Moore, all of these factors were at play. In 2013, Berkeley, California, police responded to a call from Kayla’s roommate, who told police that Kayla, a Black trans woman labeled as schizophrenic, had been drinking and using drugs and had locked him out of their apartment. According to her sister Maria Moore, Kayla was calm and cooking when the officers arrived, but they claimed that she was “speaking incoherently.” A subsequent investigation revealed that instead of asking her or her caregiver, who by then was also on the scene, what she needed, the officers misgendered Kayla, and told her there was a warrant out for her arrest. In fact, the warrant was for a person who was 20 years older than Kayla who bore the male name she had been assigned at birth. Confident that there was no warrant in her name, Kayla said she would call the FBI to prove it. The two officers forcefully took her down to the floor, where Kayla landed on her stomach. Eventually eight officers piled on top of Kayla, putting two sets of handcuffs on her and wrapping her legs together. Minutes later they realized that she had stopped breathing, but refused to give her CPR because they didn’t have a device that would keep their lips from touching hers. Her sister believes their actions were motivated by transphobia, noting that officers referred to Kayla as “it” as her body lay on the ground, partially uncovered. Kayla died at 32-years of age while on her way to the hospital. The cause of death was given as a combination of drugs and an enlarged heart, but in truth Kayla was a victim of police perceptions of Black women, trans women, people labeled with mental illness, and drug users.

Kayla Moore’s killing prompted protests in city council and Police Review Commission meetings and on the streets of Berkeley. Organizing led by Kayla’s sister has seamlessly lifted up the many identities and experiences that played a role in Kayla’s deadly encounter with police—as a Black woman, a trans woman, and a person labeled mentally ill and characterized as having a physical disability. I first learned of Kayla’s case from Andrea Pritchett, a long-standing Berkeley Copwatch organizer who attended the first workshop on police violence against women and LGBTQ people of color I had conducted in 2004. In the fall of 2013, we were both at a national Cop Watch conference organized by People’s Justice and the Justice Committee in New York City when she handed me a copy of Berkeley Copwatch’s independent report on Kayla’s case. At one of the breaks in the conference, Andrea sang a song in Kayla’s honor. Maria Moore continues to organize for justice for Kayla as part of the Say Her Name movement and with other families of people killed by police.

Ultimately, following Kayla’s death, more officers in the Berkeley police department received crisis intervention training. A commission of inquiry unanimously found that officers had violated policies against keeping arrestees prone on their stomachs for prolonged periods of time. Additionally, the Berkeley Independent Police Review Commission found that officers failed to monitor Kayla’s vital signs after piling on top of her as she lay facedown and binding her hands and feet. Despite these findings, no officer was disciplined. The family filed a civil suit, the bulk of which was dismissed in October 2016, on the grounds that the force used was not excessive and did not cause Kayla’s death. Berkeley Copwatch made a series of policy recommendations, including increased funding for psychiatric treatment and the development of alternative, nonpolice responses to mental health crises.

*

On August 14, 2014, just days after Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, Missouri, Michelle Cusseaux was at home in Phoenix, Arizona, fixing her door when a police officer, Percy Dupra, came to execute a “pickup order” to bring her to a mental health treatment facility. When officers arrived at her home, Michelle spoke with them through the door and refused to leave her home or consent to their entry. She said she did not trust them, and believed they would shoot her. Both Michelle and her mother told officers that she did not have a weapon in the house.

According to the complaint filed in a civil suit brought by Michelle’s mother, Fran Garrett, “Rather than give Michelle space and more response time, attempt to deescalate the situation, engage in additional communication with Michelle in a calm manner in order to build trust or alleviate her fears, or seek the involvement of appropriately trained personnel, Dupra instructed an Officer Anderson to pick the exterior locked door of Michelle’s residence.” When they entered, Officer Dupra saw Michelle standing near the door holding a hammer, interpreted it to be a weapon, and shot her. He later said that something about the look on her face—“eyes wide open, mouth wide open. . . She had that anger in her face that she was going to hit someone with that hammer”—caused him to fear for his safety. Fran Garrett later questioned the officer’s response: “What did the police see when they pried open that door? A Black woman? A lesbian? He said it was just a look on her face. What look would you have on your face if the police broke into your house? Could that have been the look of fear? I would have been in fear for my life too, especially if I already felt like they were going to kill me.” Once again, perceptions of Black women as “deranged subjects” prone to violence colored an officer’s response to a Black woman standing with a hammer, with deadly results.

In the wake of Michelle’s killing, her mother organized with community members, marching her casket to the US Attorney’s Office to demand an investigation into her death. In October 2014, in response to Michelle’s shooting, the Phoenix Police Department announced the creation of a Mental Health Advisory Board to guide the department’s policies. The department also instituted mobile crisis teams and crews of behavioral-health specialists, and mandated a decreased focus on arrest in favor of providing needed services and increased supervision by trained officers when executing “pickup orders” like the one that brought officers to Michelle Cusseaux’s home. Ultimately, the Phoenix Police Department found that Officer Dupra violated departmental use-of-force policies, and he was subsequently demoted but not prosecuted or fired.“ That was like a smack in the face—to find someone responsible and put him back out in the community with no evaluation, no additional training, no other consequence for taking a life,” Fran Garrett said.

*

As in Kayla’s and Michelle’s cases, police violence against people in mental health crisis often occurs in homes and facilities away from public view—and cop-watching cameras.

One winter day in 2012, one such incident took place in a Rosemead, California, community mental health clinic, where Jazmyne Ha Eng, a 40-year-old Asian woman who was a regular patient, was waiting in the lobby of Pacific Clinic’s Asian Pacific Family Center, when she was shot to death by Los Angeles County sheriffs. Clinic staff had called 911 to get someone to take Jazmyne in on an involuntary psychiatric hold. The deputies claimed that Jazmyne, who was four feet nine inches and weighed 93 pounds, had waved a hammer over her head and charged at them. Yet clinic staff had described her in the 911 call as “sitting calmly,” patiently waiting for hours. While it is unclear what exactly transpired, no doubt historic perceptions of Asian women who do not fit the “China doll” image as masculinized and dehumanized “others” played a role in transforming Jazmyne, in the officers’ eyes, from a tiny woman sitting quietly, in need of help, into a raging threat that must be met with lethal force. They no doubt also played a role in the district attorney’s office ruling that the shooting was lawful. Nevertheless, Jazmyne’s family’s litigation seeking review of police responses to people in mental health crisis resulted in a $1.8 million settlement, and investigation of the shooting resulted in “administrative action” against two deputies involved.

Controlling narratives often frame nonsubmissive Asian women as being out of control and deranged, even where no disability exists. In April 2016, Ok Jin Jun, a 62-year-old Korean woman, was followed into her church parking lot by LAPD officers after she honked at them to move their SUV, which was blocking the entrance. As she exited the car, they demanded to see her registration. Because she speaks little English, she called 911 for a translator. The officers responded by calling for backup, summoning two additional cars to the scene. Surveillance video shows them charging at the woman, pushing her up against her car, and slamming her to the ground; then, three officers piled on top of her before handcuffing her, leaving bruises and scrapes on her face. The officers’ response not only punished Jin Jun for seeking language assistance but also reflected rage at perceived failure to display the deference expected of an Asian woman, transforming an elder on her way to pray who had committed no offense whatsoever into a threat that must be met with force. The police department later claimed a “mental health” issue may have prompted the response, projecting disability onto Jin Jun where none existed and responding with violence.

*

As is the case in school settings, children are unfortunately not immune from police projections of deranged threat—even a 70-pound, 8-year-old Lakota girl in distress in her own home. In October 2014, officers responded to a call for help from a babysitter because the girl was threatening to hurt herself with a knife. Upon the officers’ arrival, the girl pointed the knife at her own chest except for a brief moment when it was pointed at one of the officers. They responded by using a Taser on her; the weapon’s 50,000 volts of electricity lifted the little girl’s body and threw it against the wall, causing her physical and emotional injuries. Subsequently, the South Dakota Division of Criminal Investigation found no wrongdoing by the officers. Her attorneys protested, “These are trained professional law enforcement officers and there were four of them. . . Not one of them thought to reach out and grab her, or talk her down. . . They came in there and dealt with her like she was a 30-year-old. . . ‘Drop the knife or else!’”

*

Controlling narratives framing Indigenous women as violently “insane” if they resist authority in any way, as well as expendable and to be eradicated, also contributed to the death of Loreal Tsingine, a 27-year-old Navajo mother who had been prescribed medication for psychosis. In March 2016, an officer responding to a call about a disturbance in a store killed Loreal within 30 seconds of approaching her on the street. The officer forcefully took her to the ground, spilling the contents of her purse, which included a pair of scissors friends say she used to cut split ends from her hair. Loreal got up immediately. The officer’s body-camera video shows Loreal walking toward him, holding the scissors pointed to the ground, with the officer’s partner behind Loreal, ready to assist in taking her into custody. Instead of working with his partner to physically restrain her, the first officer shot Loreal five times, killing her instantly. It later came to light that the officer had incurred 30 violations during his training, including falsifying evidence and being “too quick to go to his gun,” leading training officers to recommend against his hiring. He also had a history of violence toward women: he had been found to have made vulgar comments to a 15-year-old girl and had used a Taser on another 15-year-old girl with her back to him. The DOJ opened an investigation and the officer eventually resigned. Loreal’s aunt, Floranda Dempsey, mourned the young woman at her funeral, saying, “Even with a broken heart that never recovered from devastation, she showed us what love should be about. We will miss her tight hugs and beautiful smile and love.”

*

As Dara Baldwin of the National Disability Rights Network emphasizes, it is not only people with mental disabilities who are at increased risk of physical and lethal violence by police; women of color with physical disabilities are also subject to police brutality, including police sexual violence and sometimes deadly force.

Lisa Hayes, a Black school counselor living in Rehoboth, Delaware, who is quadraplegic and has a speech impediment caused by cerebral palsy, is one of them. A tactical team trained to combat “domestic terrorism” conducted a drug raid at her mother’s house. They drove up in an armored personnel carrier, armed with assault rifles, and burst into the family home at 6 am. Lisa’s husband, Ruther, a disabled veteran, was giving her a sponge bath, and tried to cover her with a sheet because she was naked from the waist down when the officers broke down the door.

The officers threw Ruther to the ground and pointed their assault rifles at Lisa as she lay half naked on the bed, screaming at her to “get the fuck up”—which she was physically unable to do. The officers were clearly on notice of this fact: her wheelchair was next to the bed; officers had stormed up a wheelchair ramp before breaking down the door; and Lisa, as well as Lisa’s mother and son, repeatedly told the officers that she couldn’t move. After being held at gunpoint for an extended period of time while officers beat and tasered her husband, Lisa told the officers she was experiencing chest pain and believed she was having a heart attack. The officers stopped beating her husband and called for medical assistance. Instead of dressing her and taking her out of the house in her wheelchair, the officers wrapped the top half of Lisa’s body in a sheet, leaving the bottom exposed, and carried her out by the arms and legs, half naked in front of her neighbors. After the incident Lisa said, “I feel not only degraded, humiliated; I feel like they didn’t treat me as a human being. I relive that day when they came in on me and them yelling at me to get up when they knew that I couldn’t get up.” She continues to suffer flashbacks of the raid, depression, panic attacks, and chest pain. The ACLU filed a lawsuit on the couple’s behalf.

*

Police interactions with deaf people are notoriously dangerous because in the absence of interpretation, deaf people are perceived to be “noncompliant.” Lashonn White, a Black deaf woman, called 911 to report that she was being abused by another woman in her home, and repeatedly pleaded for help. Throughout the call, she emphasized that she required a sign-language interpreter in order to communicate with hearing people.

After she followed the dispatcher’s instructions to go out her front door to meet police, Lashonn was immediately Tasered in the ribs and stomach by the officers, causing injuries to her cheek, chin, ribs, neck, and arms and leaving her bloody. She later said, “All I’m doing is waving my hands in the air, and the next thing I know, I’m on the ground and then handcuffed. It was almost like I blacked out. I was so dizzy and disoriented.”

Hearing Lashonn screaming in pain, her neighbor yelled down to officers that the woman was deaf and couldn’t speak and criticized them for not signaling her to stop using hand signals instead of verbal commands. One officer later said he thought that Lashonn, who was running toward him for help as instructed, was “charging at him,” and describing her as “making a loud grunting noise, [having] a piercing stare in her eyes and . . . a clenched right fist in the air.” Police also claimed that they mistakenly believed she was the assailant, despite having been given a detailed description, which did not match what Lashonn was wearing.

As with Michelle Cusseaux, all it took was a “look” to transform Lashonn from a person desperate for police intervention into a dangerous threat in the eyes of officers. Officers charged Lashonn with assault and obstruction of justice, invoking images of her as animalistic—“deranged” and “grunting”—to justify their actions. Lashonn was taken to jail and held for 60 hours without medical treatment or an interpreter, in violation of state law, until the prosecutor dropped the charges. While a jury in a civil case brought by Lashonn believed that her rights had been violated during the arrest, they awarded her only one dollar in damages, making clear how much value they placed on her Black deaf life.

__________________________________

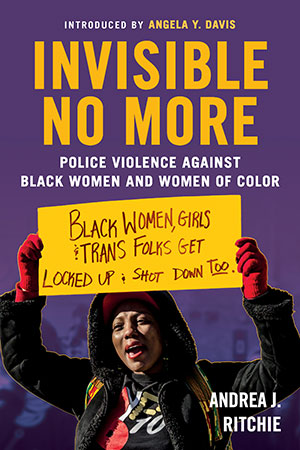

Excerpted from Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color by Andrea J. Ritchie (Beacon Press, 2017). Reprinted with Permission from Beacon Press.

Andrea J. Ritchie

Andrea J. Ritchie is a Black lesbian immigrant and police-misconduct attorney, and a 2014 Senior Soros Justice Fellow, with more than two decades of experience advocating against police violence and the criminalization of women and LGBTQ people of color. She is currently Researcher-in-Residence on Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Criminalization at the Barnard Center for Research on Women and the coauthor of Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women (AAPF, 2015) and Queer (In)Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States (Beacon, 2011). She lives in Brooklyn, New York, and Chicago.