Men of Power and Their Obsession with Winston Churchill

Visiting the World's Foremost (and Only) Bookstore Devoted to Churchill

“What makes a leader? Do leaders have common traits, or are these defined by the challenges and circumstance of the times? What does it take to lead a business in the context of a changing economic landscape? What should businesses expect of those leading them into the uncertainties of tomorrow?

As part of its 16th Annual Global CEO Survey, PwC recently asked 1,400 CEOs from around the world which leaders they most admired, and what they most admired about their actions […] Winston Churchill was the most popular choice.”

–PricewaterhouseCoopers Press Release, April 15, 2013

Few have shaped the course of modern history as decisively as Winston Churchill. Were it not for his leadership in World War II, or so the story goes, the Allies might have lost; we’d be living in a frightful parallel universe. He looms large in our collective imagination: pug-faced, cigarred, always ready with a bon mot. Especially in the United States, where his shortcomings are easily ignored, Churchill stands as the ultimate wartime leader. Both Bernie Sanders and Ted Cruz can cite him as a political hero, evoking England’s “finest hour” under his command. They’ll even tell the same story: how after a decade of unheeded warnings about Hitler—about the dangers of appeasement—Churchill was called upon, at Europe’s nadir, to fix the very problem he’d foreseen. Against fearful odds, he then led the good guys to victory, rousing his people with top-notch political rhetoric: “blood, toil, tears and sweat,” “we shall fight on the beaches,” and so on.

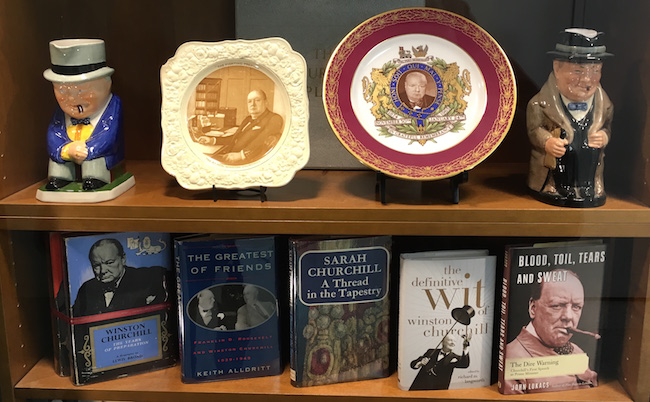

Today, Churchill constitutes a publishing industry unto himself. Dozens of new books are released each year with his name on their covers, and most end up for sale at Chartwell Booksellers—the only bookstore devoted to works by and about the Prime Minister. You’d expect to find such a place in London, but it’s located in the heart of midtown Manhattan, just across from the Seagram Building. Park Avenue Plaza, the tower that houses it, is unremarkable in most respects—shiny green glass on the outside, corporate offices within; a lobby with bamboo shoots, a Starbucks, and carved out logos: Morgan Stanley, Intercontinental Exchange, McKinsey and Company, Blackrock. These are strange bedfellows for an independent bookstore—let alone the last one standing in all of midtown. Yet if you walk down the lobby hallway, there it is: Chartwell Booksellers, inviting and bright.

Chartwell was the name of Churchill’s country house in Kent, and in 1983 it became the name of Barry Singer’s midtown bookstore. A 22-year-old music journalist at the time, Singer stumbled into the job. Chance had it that Richard Fisher, scion of one of Manhattan’s richest real estate families, dreamed of opening a bookstore in his new building. So when Fisher met the young Rolling Stone writer, he asked the kid what kind of bookstore he’d build if given free rein. “I described a fantasy of an English library,” Singer recalls, “an oasis away from the world, hand-carved oak bookshelves.” Fisher asked him to put together a five-year plan, and, next thing you know, they were in business. Fisher would put down the money; Singer would handle everything else. “Build it however you want,” the real estate mogul told the writer, handing over a small room in the lobby hallway of his tower. “But since I love Churchill, would you mind calling it Chartwell?”[1]

Beyond that, it had nothing to do with the Prime Minister. Chartwell was an independent bookstore like any other. But a seed had been planted. Because of the name, Singer stocked a handful of Churchill titles; and in his introductory newsletter to the building’s tenants—corporate lawyers, consultants, financiers, and Henry Kissinger—he mentioned “two new additions to our Churchill rare books department.” There was no such department, needless to say, but Singer received a call, almost immediately, from the office of Saul Steinberg, a famous corporate raider at the time. “He was kind of the devil incarnate,” Singer recalls. “Movies like Wall Street were about Saul—they really were.” And now his secretary was on the line, calling from way upstairs. “Mr. Steinberg will take those Churchill books from your newsletter,” she said. “And while you’re at it, would you get him leather-bound first editions of everything he ever wrote?”

Keep in mind: Churchill published 42 books in his lifetime—starting with war journalism from his early years in India and Egypt; and going all the way through to biographies of his illustrious ancestors; to epic multi-volume works like A History of the English Speaking Peoples. “He wrote to pay the bills,” as Singer puts it. “Every time he had something due, he wrote a new book.” He wrote enough to earn a Nobel Prize in literature. So to request everything he wrote in first edition is to place a very expensive order indeed. It’s the kind of order large enough to nudge Singer down a Churchill wormhole, from which both he and his bookstore have yet to emerge.

Motivated by Steinberg’s request and others like it, Singer began educating himself about the market for Churchinallia. Within a few years, his store became the place to go for a Churchill first edition; for a complete copy of Martin Gilbert’s eight-volume Churchill biography; or for the latest Churchill history put out by a major publisher. It became “the Churchill bookstore” we know today—not because of Singer’s abiding interest in the subject, but—as befits a place surrounded by hedge funds and private equity firms—because of market forces, plain and simple. The kinds of people who worked in Park Avenue Plaza happened to love Winston Churchill; and Churchill, rather conveniently, happened to be endlessly collectible. As Singer puts it, “I realized, when Barnes and Noble first appeared on the scene, and then later with Amazon, that we couldn’t survive as a general interest bookstore. But with a specialty, we would do fine—and that specialty was Churchill.”

All these years later, I like to think of Singer as a kind of anthropologist. Sure, he’s learned a great deal about Churchill. But more than that, he’s learned about the kinds of people who love him. Picture the decades spent near the register at Chartwell; think of the implicit invitation it extends to all customers: come in, unload those Churchill stories you’ve been carrying around. “Very few people come in to just look,” Singer concedes. “A lot come in to tell you what they know. A lot of people. And I would say that 75 percent of them like to repeat some of the dopiest and in many cases most questionable anecdotes about Churchill.”

Others come in to air political grievances. “A bookstore devoted to Churchill!” someone once yelled, poking his head through the door. “That’s insane! Why not just devote a whole bookstore to George Bush!” After all, Churchill was a staunch colonialist, who believed in England’s “high mission to rule over primitive but agreeable races for their welfare and our own.” And he pursued this mission, often violently, throughout his long career—quashing independence movements in India, Kenya, and Iraq, to name a few. Not to mention the careless job he and others did carving up borders after World War I in the Middle East; or the extreme brutality of his attacks on civilian targets in World War II; or his well-documented obsession with chemical warfare; or his 1953 overthrow (with the CIA’s help) of democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossaddegh in Iran. These are just a few of the charges one could level against him.

Not that Singer gave any of them much thought before opening his store. “I was aware of Churchill as the man who saved Europe in WWII,” he says. But that was it. “Though I did have a very vivid memory of watching, as a child, Churchill’s funeral on TV. I had no idea who he was, but it was so grand, and it went on for so long, that it made a real impression. I thought, who is this guy?” Well, Singer found out, and today he’s grateful for such a fascinating subject. “I’ve benefited enormously from this close exposure to Churchill,” he says. “I’ve learned a lot from him about living. First: his resiliency in defeat. Because he lost at least four elections, and was put out of office repeatedly, including before the Second World War was over. He made a lot of mistakes over the years, and he evolved. And second: his magnanimity. Churchill was amazingly magnanimous towards his [political] enemies.”

Prominently piled near the cash register are a dozen signed copies of a slim red volume called Churchill Style: The Art of Being Winston Churchill, by Barry Singer. It’s a revealing title, coming as it does from Chartwell’s founder. After all—and here I’m just speculating—Singer understands better than anyone Churchill’s appeal to wealthy executives. He knows that for his customers, it’s not enough to read about the wartime leader. They want to buy up his first editions and manuscripts, too; to own a piece of him, or as close to a piece of him, as they can. Even more than that, they aspire to be like Churchill themselves. And Singer’s biography, with sidebar sections likes “Imbibing,” “Books,” and “Cigars,” provides an initial road map toward this goal. It tells us what Churchill drank, where he got his clothes tailored, and which books he read.[2]

“There’s something to that,” Singer says, when I lay out my theory. “But I’ll tell you something else: In most respects, no matter who those people are, I think the aspiration to be like Churchill is the best part of them. Whatever they want to emulate—whether it’s a more refined way of living, or a more firm line in their power of negotiation—I think it’s more ennobling than it is malicious. Like Saul Steinberg, who I liked a lot. He was a ruthless man who did ruthless things, in terms of hostile corporate takeovers. His mind worked very fast into, you know, how to get what I want. But he had a very clear sense of who Winston Churchill was, of what was great about Churchill. He really read the books, and it was one of his saving graces, I felt. Even in politics, I’ve spoken at conferences with rabidly right wing, virulently anti-Obama audiences—and they claim Churchill as their own. But as ugly as it gets, the things that they want to be like Churchill for are still better than what they are. His presence is sometimes the only civilizing factor in an otherwise bestial environment.”

I ask Singer—now in his fifties, with slicked back gray hair—to describe his typical high-end customer, and he sums it up as “largely powerful men. Not only in finance, but significantly, a number of them are in finance.” He pauses and weighs his words before continuing. “I always say, and I’ve come to believe it, that everybody can find in Churchill whatever they want to project onto him, because there were so many facets to his personality.” Still, for all that complexity, Churchill’s admirers tend to focus on his fight with Hitler. “The more powerful they are,” Singer says, about his customers, “the more they relate to the idea of Churchill as anti-appeasement, as standing up to Hitler. They want to see things that show Churchill’s strength and foresight, and Churchill’s power to stand up against everyone else, to say no, it has to be like this.” Singer pauses before adding a personal caveat. “One of the things I’ve learned, studying Churchill all these years, is that everything about him was more nuanced than the simplistic historical view would suggest.”

The negative side effects of this simplification are keenly felt in American politics. Think back to 2001, a few months before 9/11, when George W. Bush installed a bust of Churchill in the oval office. In doing so, he praised the Prime Minister for, essentially, being just like him: Churchill “knew what he believed,” Bush said, in his inimitable cadence, “and he really kind of went after it in a way that seemed like a Texan to me. He wasn’t afraid of public opinion polls. He didn’t need focus groups to tell him what was right. He charged ahead, and the world is better for it.” Alas, a few years later, Bush saw himself as similarly intrepid.

And then there’s the frequency with which “appeasement” is used as a line of rhetorical attack. Donald Rumsfeld was a big fan of this approach, accusing Iraq War skeptics of repeating Chamberlain’s mistakes. In one address, from 2006, he quoted Churchill’s quip: accommodating Hitler, the Prime Minister said, is “like feeding a crocodile, hoping it would eat you last.” And we face a comparable evil, Rumsfeld continued, in our fight against terror. “Can we truly afford to believe that somehow, some way, vicious extremists can be appeased?”

These analogies have grown only more frequent in recent years, and the “appeaser” label seems to have coalesced around Obama in particular. His willingness to strike a deal with Iran, his reluctance to deploy ground troops against ISIS, and his refusal to say the phrase “radical Islam” all reveal, per Fox News and co., the depths of his denial. As John McCain said on The O’Reilly Factor a few years ago: “President Obama is operating in the finest traditions of Neville Chamberlain, who once said we’re not going to send our young men to a country that we have not been to and speak a language we do not know.”

Singer grows animated when I bring up this rhetorical trend. “You can’t make those claims easily with an educated sense of Churchill,” he says. “Because Churchill’s belief was that there should not have been a Second World War. He wasn’t willing to go to war just for the sake of going to war, or to show how powerful he was. And he thought if we stood up to Hitler at the right time, there would have not been a war. So when people say, Churchill is my guy because he’s the strong one—they don’t understand that it was strength in the name of peace.”

Many on the right might quibble with this assessment, but what would really raise their eyebrows is Singer’s subsequent claim—that Obama, of all our presidents, is the most Churchillian. “Churchill was dismissed and obstructed throughout his career in parliament,” he explains. “Even by his own party—Conservatives didn’t trust him, and they drummed him out with Chamberlain. So to survive that, and come back, and still be a leader… I think without question Obama is the most like Churchill. And he’s one of the few presidents we’ve had, at least in my lifetime, who’s actually a reader, a thinker, and a writer. But when I say that to people—that there’s a lot of Churchill in Obama—there are gasps. At a conference, I had to literally collect my check and get out of the building after saying that. Maybe that should be my next book: Churchill and Obama.”

What about Trump? I ask, half in jest. Don’t his supporters, at least some of them, see him as Churchillian—you know, identifying the Nazi-grade threat of jihadism? “There’s nothing about Trump that resembles Churchill,” Singer says. “Though I do think that there are many things, aside from the vilest things, that Trump has in common with Adolf Hitler. Hitler was a showman. He conducted the war like a reality TV show. It was very much about display, about pomp, about surfaces, about screaming and yelling and saying really awful things that no one else would say. It reminds me a lot of Donald Trump, actually.”

“Hitler was a showman. He conducted the war like a reality TV show. It was very much about display, about pomp, about surfaces, about screaming and yelling and saying really awful things that no one else would say. It reminds me a lot of Donald Trump, actually.”When we finish talking, I step out and notice a baby grand piano just opposite the door. At its keys an older man with gaunt features and a fedora plays solo jazz. His improvisations—which nobody else is around to hear—strike me as a suitably strange soundtrack for Chartwell’s display windows. In one of them, the contents of an elaborate board game are laid out: Mark Herman’s Churchill: Big Three Struggle for Peace. From what I gather, the point is to act out parallel versions of the Yalta conference, as either Stalin, Churchill, or FDR.

In another, an original oil painting by Churchill holds pride of place. Entitled Silver Life, it was painted in the 1930s, Churchill’s so-called “Wilderness Years,” when he was forced out of government, and made his living as a writer. In his spare time, he painted for pleasure: landscapes and, occasionally, still lives such as this one.[3] According to Chartwell’s glossy catalogue, “to appreciate this painting up close is to marvel at Churchill’s unexpectedly tactile impasto technique, the lustrous physicality of his brush strokes.” There is, I have to admit, a visible ease behind its strokes—enough to suggests that Churchill painted just as confidently as he governed. A few big bold swerves here and there—yellow, white, various greys—and there’s your still life: two silver vases and an ashtray. Not the most impressive painting you’ll ever see, but one that provides a fascinating window into Churchill’s mind. For a quarter million dollars, it could be yours.

Across the way, one of his Davidoff cigar butts is handsomely encased, with a handwritten note attesting to its authenticity: “smoked by Mr. Churchill on Jan 30th 1952.” This bit of refuse is, I suppose, a modern-day religious relic. But its sale would not have surprised Churchill. After all, he often asked assistants to gather his used cigars when he left a room, eager as he was to avoid the embarrassing and all too common spectacle of people pouncing behind him for souvenirs.

I head back inside, and Singer pulls out some highlights from his current batch of rare materials. A first edition of My Early Life, with dust jacket intact, goes for $25,000. It’ll in all likelihood soon end up on a hedge fund manager’s shelf. Singer also shows me a few of Churchill’s letters, like the one to General Arnold (29 May, 1942), saying thanks for the crate of oranges, which are “are all too rare at present.” In another, from 1902, Churchill apologizes to his friend John Morley. “Dinner tonight,” he writes, “has fallen through.”

Singer shows me one last item before I leave. It’s a copy of Arms and Covenant, Churchill’s 1938 collection of speeches about Hitler. Here, in palpable form, are his lucid warnings in the lead-up to war. The book is signed by Churchill, and dated in his hand. August 1938, the same month Nazis required German Jews to add Sarah or Israel to their names on passports. A month before Neville Chamberlain signed the Munich Agreement, handing over Czechoslovakia to Hitler without a fight. “This is powerful,” Singer says. “You’re really holding a piece of history.”

On my way out, I stop in front of Chartwell’s literature section and let my eye wander along its titles. Viewed in their context, under Churchill’s shadow, the books take on new kinds of meaning. I see Speak Memory, in which Nabokov recounts his brother’s death during the war—killed by the Nazi regime for speaking out in protest. Nabokov himself was exiled because of Hitler; he left Germany for France in 1937, and fled to the United States in 1940.

Nearby, in the small poetry section, W.H. Auden writes, in “September 1, 1939,” about the war just breaking out; he addresses us “as the clever hopes expire / of a low dishonest decade.” A few books down, Selected Poems and Prose of Paul Celan is hard to miss. The Romanian Jewish poet managed to escape his Nazi labor camp during the war, but his parents, like millions of others, were not so lucky. For the rest of his life, on and off the page, Celan grappled with the Holocaust’s horror. He wrote in German, which had passed through “the thousand darknesses of deathbringing speech.” And then, in 1970, he committed suicide.

Countless lives were shaped, in big ways and small, by the Second World War, and, because the two are inseparable, by Churchill. Most of us remember him as the guy who saved us from fascism, who saw the Nazi threat for what it was and led the Allies to hard-fought, if imperfect, victory. With the passage of time, he perhaps has grown into a kind of caricature—a “great man” fetishized by corporate executives, his legacy exploited by lesser politicians. But whatever we make of him, we can at least be grateful for Chartwell Booksellers. For in gathering together the literature by and about Winston Churchill; in encouraging us to recognize the complexity of his legacy; and in demonstrating the process by which history becomes commodified, it compels us, if nothing else, to take a closer look.

[1] In case you’re wondering, the Fisher Brothers real estate company is now run by Winston Fisher, Richard’s son.

[2] To be fair, it also provides an excellent, albeit overtly sympathetic, overview of Churchill’s long, tumultuous career—painting a deft picture of what he was like as a person rather than deity.

[3] It was Churchill’s book on the subject, Painting as Pastime, that recently inspired George W. Bush to explore his inner-Rembrandt.