Memories of the Pogroms: Understanding History Through Family Stories

Lisa Brahin on What She Learned From Her Grandmother

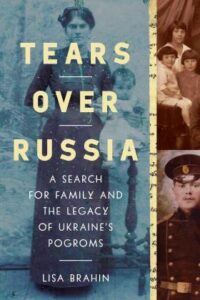

As a child, I was drawn to an old sepia-toned photograph taken in Russia that stood proudly on my great-grandmother’s shelf. The Cabinet Portrait showed her as a stunning young brunette propping up her infant daughter on a four-legged stand. It was my first clue that another world preceded mine, and the image of my great-grandmother and grandmother living a different reality ignited within me a lifetime desire to learn every detail of their past.

When Great-Grandma died in July 1972, I was nine years old and visiting my grandparents in the Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York, as I did every summer vacation. During that visit, it occurred to me that many of our family’s secrets died with the passing of my oldest relative.

I regretted not tapping her on the shoulder and asking her, “What was your grandmother’s name?” or “What was your wedding like?” or “Who else in our family missed the boat to America?” I know that she would have been moved and happy had I expressed interest in the family’s past.

So, I did the next best thing. I directed my questions to her daughter, my grandmother Anne. One night I couldn’t sleep, and Grandma came into my room and started humming and patting my shoulder.

“Grandma,” I asked her in the wee hours of the morning, “Why did your mother call you Channa?”

“It’s my Jewish name from Russia,” she answered.

“Please, Grandma,” I begged her, “tell me about when you met the bandits in Russia.”

At first, she didn’t take my interest seriously.

“Honey,” she answered, “wouldn’t you rather I make you a cup of hot chocolate?”

I already knew that my grandmother’s happiest childhood memories, in the years just preceding the Revolution, were of playing and picking flowers on Count Branicki’s estate. As a young girl, I watched as Grandma planted lilac bushes on the property line of my mother’s home in New Jersey. She said that this reminded her of the purple lilacs in bloom that formed a hedge in the count’s botanical gardens, a constant attribute to springtime in her native town, Stavishche, Russia, located today in Ukraine.

Now I was delving into memories that she would rather forget. Faced with the dilemma of how to entertain a young insomniac, Grandma eventually came to learn that the only way I would fall asleep was by listening to the soft sound of her voice as she described in detail her early childhood in Russia. I was barely old enough then to understand the implication and weight of her words, but I sensed that my mother’s mother had lived through turbulent times that continued to plague her throughout her life.

After hearing my grandmother Anne’s secrets and stories, it became clear to me why she battled with nervous phobias. There were too many “episodes” to count, but her one brave attempt to ride an elevator with me when I was a child made the most lasting impression. On our way to a department store fashion show, wearing matching spring hats, we were unexpectedly directed to an upper floor. When the elevator doors closed, absolute panic set in. Grandma couldn’t catch her breath and anxiously pressed every button to get out.

My grandmother was so fearful of enclosed spaces that even as an elderly lady, she opted to take the stairs. Her claustrophobia was an unwelcome result of the trauma she endured during the anti-Jewish pogroms of 1918-1920, when she spent her days hiding in crawlspaces. As a little girl, she was caught in pandemonium as her village evacuated, and people ran for their lives. The chaos that she survived shaped fears that haunted her for nearly ninety years.

The chaos that she survived shaped fears that haunted her for nearly ninety years.

Grandma Anne’s story is not about the Holocaust but rather a prelude, twenty years earlier, of the horror that was to come. She was a young Jewish girl born into a world that refused to tolerate or accept Jews and their way of life. In fact, she lived in a world that did not want Jews at all.

As a young teenager, I decided that the intelligent thing to do was to tape-record Grandma’s stories so that, in years to come, I could write a biography of the events leading up to my ancestors’ voyage to America. Unfortunately, because of my grandmother’s nervousness, the stories flowed better when the cassette wasn’t turned on. The minute she saw the tape recorder in front of her, she froze.

Grandma Anne finally relaxed after I suggested that she should pretend I was the only one who would ever hear what she said. She began recounting her miraculous tales, and, after dozens of hours of successful storytelling, I was proud of myself for having recorded them for posterity. However, posterity didn’t last as long as I had expected. Late one evening, when I decided to listen to the many recordings, I realized that the machine had malfunctioned; the tapes were blank.

My grandmother, disappointed that so many hours of her storytelling were all in vain, agreed to redo the many taping sessions while waiting for the bus to arrive at her new condominium in Florida to take her to nightly bridge games.

During my many visits with Grandma in the late seventies, I followed her, with a microphone in hand, and we bonded at that bus stop.

Grandma Anne’s vivid accounts of her family’s survival during Russia’s deadliest wave of pogroms—when estimates ranging from well over one hundred thousand to nearly a quarter of a million Jews were annihilated during scores of riots that swept across the country—left me searching for answers. I craved more information about this historical nightmare that befell my family in Grandma’s childhood town of Stavishche.

My curiosity only heightened when I discovered that there was almost nothing published about this time period. As a young newlywed contemplating my own future, I could not help but wonder: Where was this mysterious place on the other side of the earth, where my grandmother’s world began and then so abruptly fell apart?

It was upstairs, in a back room of the historic Free Library of Philadelphia, where I first experienced the exhilaration of pinpointing Stavishche on a map. I stood over an old photocopier with a pile of change and printed out sections of the magnified page from a large atlas that covered a thirty-mile radius. I then carefully matched the pages and Scotch-taped them all together.

With absolute delight, I circled all the obscure villages near Kiev whose names I had heard over and over again during my own childhood: Stavishche, Skibin, Zhashkov, Tarashcha, Sokolovka, and Belaya Tserkov.

I tucked the map in an envelope, sent it off to Grandma in Florida, and eagerly awaited her reaction. In a letter dated May 25, 1984, I received a thrilling answer. “Dear Lisa,” Grandma wrote. “I’m getting a big kick reading the map you sent. Where were you able to find a blown-up map from the area? I finally saw the town in print, where I was born. Now I can confirm that I was really born somewhere.”

Throughout the years, my thirst for information never ceased. My unyielding determination to piece together the puzzle of the past set me on a path to pursue what has become my lifelong passion—Jewish genealogy. I began by writing to curators around the world, who combed their archives for unpublished, mostly handwritten, documents and manuscripts about the pogroms in her area.

Many of these elusive sources had been collecting dust for decades while sitting on shelves in New York City; Washington, DC; Kiev; Warsaw; Jerusalem; and Tel Aviv. With the assistance of a number of talented linguists, mostly volunteers, who pored over the Yiddish, Hebrew, Russian, Ukrainian, and Polish pages, my grandmother’s tales were at last historically validated.

Many years after conducting interviews with my grandmother and the last generation of Jews to live in the town, I was determined to tap one last wealth of unpublished sources—family histories. With doors now opened by the Internet, families with ties to Stavishche living in seven countries around the world shared their personal stories with me.

What I didn’t expect during this fascinating journey were the many exciting anecdotes that would emerge of colorful personalities of the day. Their accounts painted a portrait of the town, bringing light to an entire group of people who lived so long ago.

In the end, despite her hesitation and constant battle with nerves, Grandma was at peace with having entrusted me with the details of her most private experiences, knowing that I intended to thoroughly research and chronicle her saga. Scholarly materials and eloquent testimonies from her childhood neighbors that I gathered in the years following our taping sessions are woven into this narrative, enhancing my grandmother’s viewpoint, which remains the fulcrum of my new book, Tears Over Russia.

In February 2003, Grandma Anne succumbed to pneumonia and was buried alongside my grandfather—her husband of sixty-six years—at my synagogue’s cemetery in Neptune, New Jersey. The week of her death coincided with a major snowstorm, and the ground was both frozen and muddy. At her graveside, a handful of family members and friends gathered together, shivering under umbrellas, sharing their memories of this wonderful woman.

During the eulogy, while a sleet-like rain pummeled us, I stood there thinking that although Grandma finally “went to sleep” (a phrase that she often used referring to death), I would see to it that her stories would never die.

Many thanks, Grandma.

_____________________________

Excerpted from Tears Over Russia by Lisa Brahin, available via Pegasus Books. Used with permission of the publisher. Copyright 2022 by Lisa Brahin.

Lisa Brahin

Lisa Brahin is an accomplished Jewish genealogist and researcher. In 2003, she helped rediscover the lost location of the original hand-written manuscript Megilat HaTevah (Scroll of the Slaughter), which she considers one of the most important documents ever recorded on the Russian pogroms. A graduate of George Washington University's Columbian College, she is a two-town project coordinator for Jewishgen.org's international Yizkor Book Project (Holocaust Memorial Book Project).