Memories Lost and Found: On the Photography of Binh Danh

“Precious things lost are transmutable. They refuse oblivion.”

When I was eleven years old, I did an unforgivable thing: I set my family photos on fire. We were living in Saigon at the time, and as Viet Cong tanks rolled toward the edge of the city, my mother, half-crazed with fear, ordered me to get rid of everything incriminating.

Obediently, I removed pictures from the album pages, diplomas from their glass frames, film reels from metal canisters, letters from desk drawers. I put them all in a pile in the backyard and lit a match. When I was done, the mementos of three generations had turned into ashes.

Only years later in America did I begin to regret the act. A few pictures survived because my older brother, who was a foreign student, had taken them with him. But why didn’t I save the rest, the way I slipped my stamp collection in my backpack hours before we boarded the C-130 cargo plane and headed for Guam? For years I could not look at friends’ family photo albums without feeling remorse.

Then last week I had a dream that was so instructive it left me with a different estimation of that loss. In the dream, I find myself once more in front of my old home in Saigon. I walk through the rusted iron gate to find, to my horror, the place gutted—an empty structure where once there was life and love.

What I failed to retrieve in the dream survives, if only as an exquisite longing.

Immediately, I start to rummage among the pile of broken bricks and fallen plasters, finding, at last, a nightstand that once belonged to my mother. I pull at its drawer and out spill dozens of black-and-white photos. I am ecstatic. The photos are intact.

They are exactly as I remember them. Here’s one of my brother when he was twelve, wearing his martial art uniform and bowing to the camera. Here’s one of my mother as a teenager, posing next to the ruins of Angkor Wat. Here is my father as a young and handsome colonel, smoking a cigar. And me and my sister holding onto our dogs—Medor and Nina—as we wave to the photographer, smiling happily.

Suddenly a little boy appears in the dream. “This is my home,” he yells, “and you’re trespassing.”

“But these are my photos,” I meekly protest.

The boy looks at me with suspicion and shrewdness and changes his tone. “Well,” he says, “how much would you give me for these photos?”

But before I can find the answer, the boy laughs and snatches the photos out of my hand. I try to grab them back of course, but it’s too late.

I woke to find my arm still reaching out over the blanket in a gesture toward the pictures, still trying to retrieve them. Confused and astonished, I stared at my own empty hand for what seemed to be a long, long time. In that salty dawn with the cable cars rumbling up the hills and their bells clanging merrily outside my window, I saw what I hadn’t seen before: that nothing was ever truly lost.

What I failed to retrieve in the dream survives, if only as an exquisite longing. If words and language, as the poet Rilke tells us, can be made into a thing, mute as the statue of an orator, the reverse is true also.

Precious things lost are transmutable. They refuse oblivion. They simply wait to be rendered into testimonies, into stories and songs.

–Andrew Lam

*

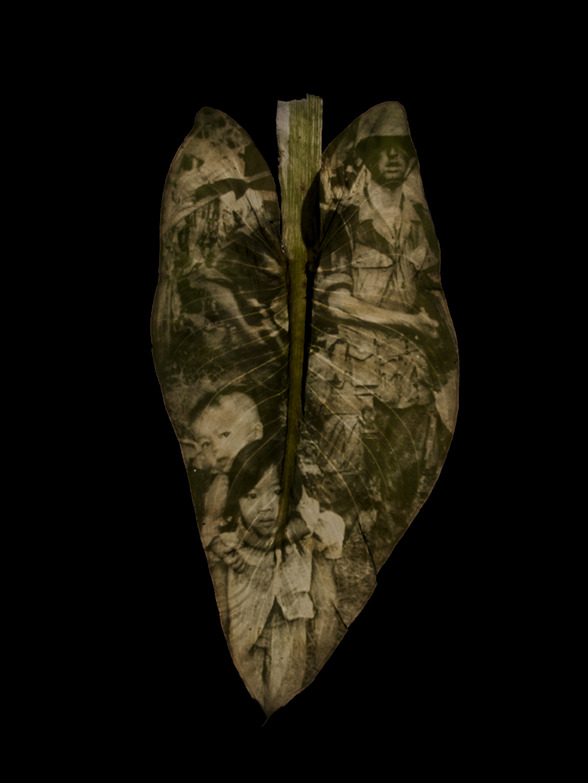

Ambush in the Leaf, 2007 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

Ambush in the Leaf, 2007 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

Untitled #4, 2009 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

Untitled #4, 2009 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

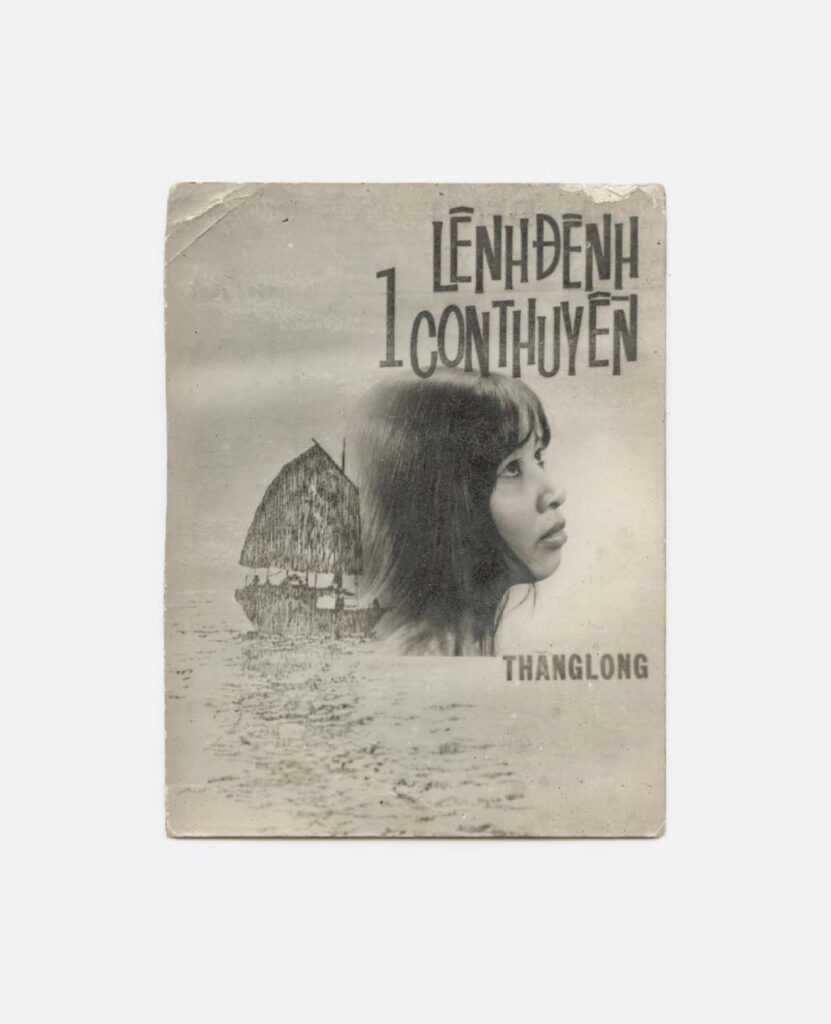

Waiting, 2009 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

Waiting, 2009 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

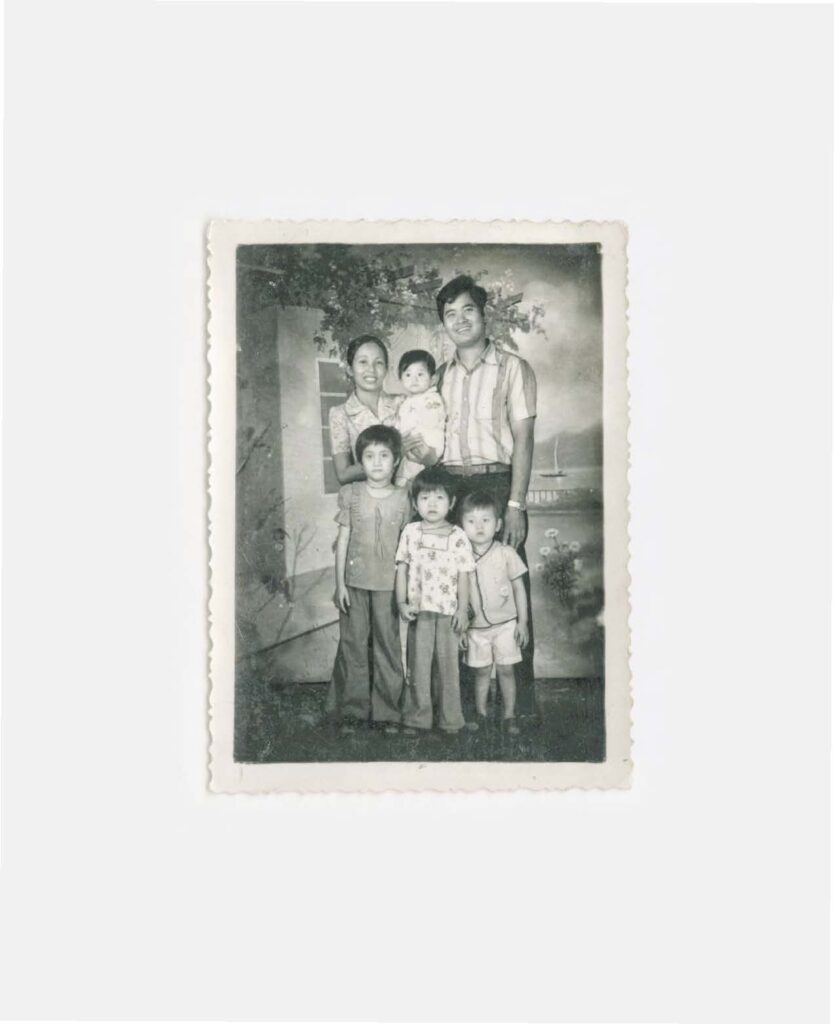

Archival Family Photograph, c. early 1978 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

Archival Family Photograph, c. early 1978 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

Archival Family Photograph, c. early 1978 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

Archival Family Photograph, c. early 1978 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

Archival Family Photograph, c. 1966 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

Archival Family Photograph, c. 1966 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

Archival Family Photograph, c. 1981 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

Archival Family Photograph, c. 1981 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

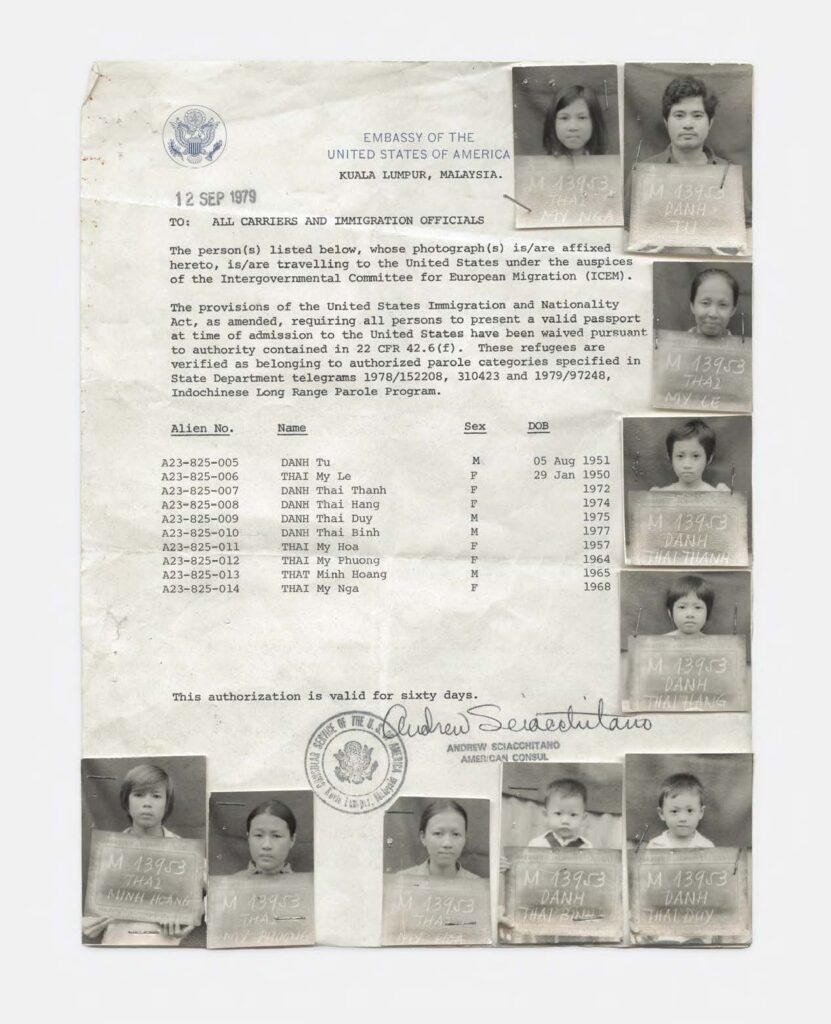

Immigration Paperwork, c. 1979 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

Immigration Paperwork, c. 1979 © Binh Danh, from Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging © Radius Books.

__________________________________

From Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging. Photography by Binh Danh. Texts by Binh Danh, Boreth Ly, Joshua Chuang, Isabelle Thuy Pelaud, and Andrew Lam. Copyright © 2023. Available from Radius Books.

Binh Danh

Binh Danh reconfigures traditional photographic techniques and processes in unconventional ways to delve into the connection between history, identity, and place. Danh is noted for his contemporary daguerreotypes of national parks. Their reflective surfaces enable people of all backgrounds to see themselves as a part of the beauty of the American landscape. His work has been collected by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the National Gallery of Art, Washington; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and the San Jose Museum of Art, among others. He is an associate professor of art at San José State University. His monograph Binh Danh: The Enigma of Belonging was the inaugural recipient of the Minami Book Grant for Asian American Visual Artists at Radius Books in 2023.