War: A Memorial Day Reading List

Searching for Illusive Truth in the Literature of Conflict

Memorial Day as summer’s gateway is a relatively young notion. A federal law moving the holiday to the last Monday of the month was passed in 1968, and enacted three years later—around the same time President Nixon eliminated the draft and created an all-volunteer force, which effectively ended America’s upper and middle classes’ engagement with its armed forces. If Memorial Day in 2015 is more associated with trips to the beach and mattress sales than it is with remembering the war dead, that seems partly by design.

In an era of that all-volunteer force, of brushfire wars and clandestine Navy SEAL missions, of dueling bin Laden-raid narratives and drones, so many f’ing drones, the disassociation and distance between the American citizenry and America’s wars can feel vast. Because, well—it is vast. But, presuming one pays their taxes, we’re all a part of it. Which makes the struggle to be involved with what our soldiers and sailors are doing in our name all the more imperative, to substantively know the human consequences of these wars all the more essential. Because we’re all responsible.

To wit: in Iraq, my scout platoon and I didn’t just wear the lightning bolt patch of the 25th Infantry Division. We wore the American flag on our shoulders, too.

As in Orwell’s time of universal deceit, telling the truth remains a revolutionary act. Where better to find truth—or at least something that aspires for it—than in literature? Who better to seek it, to tell it, than writers?

Do the subversive thing today, any day. Defy the masters of the American war machine. Read about war and conflict, be it the human experience of the civilian or the human experience of the journalist or the human experience of the combatant. Here are fourteen such texts, worthy of consideration:

SLIDESHOW: A Memorial Day Reading List

- This tremendous novel chronicles the build-up to, and the horrors of, the Nigerian Civil War, which occurred in the late 1960s. Adichie deftly explores matters of identity and African politics through a wide variety of characters, such as the sophisticate Olanna, the village boy Ugwu, and the British expat Richard. All the while, the Republic of Biafra rises to fall.

- Babel did for Russia what the World War I poets did for the West–he stripped bare the romanticism surrounding war and exposed it for its ravages, its fundamental darkness. Though technically a collection of fictional short stories, the contents of Red Cavalry were heavily influenced by Babel’s work as an embedded journalist during the Polish-Soviet War, and the story “My First Goose” remains a masterwork of form.

- A poetic mediation on the Question(s) of Palestine, this memoir follows Barghouti through his thirty-year exile from his homeland, then back to the land and city that’d reared him. Less interested in providing cut-and-dry solutions than it is confronting the overlaps of imagination and reality, I Saw Ramallah was awarded the esteemed Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature in 1997.

- A gritty, uncompromising recollection of Beah’s time as a child soldier during the Sierra Leone Civil War. It’s not easy reading, but it is urgent reading, especially as the author chronicles the slow, severe process of recouping lost humanity. Beah made the jump to fiction with his 2014 novel Radiance of Tomorrow.

- The perfect counterpoint to anyone making the dull claim that women can’t write about conflict, The People of Forever Are Not Afraid depicts modern life in the Israeli Defense Forces, where the threat of a sniper’s bullet and youthful revelry swirl together day after day, for patrol after patrol.

- I mean, it’s Didion! It’s Didion writing about the American withdrawal from Vietnam! If you haven’t read this yet, you now know how your long weekend will be spent.

- A luminous and savage depiction of post-9/11 America, as experienced by one young war hero attending a Dallas Cowboys game. It’s dark, it’s funny, and the writing pops on every page. We veteran-writers can be a crabby and disagreeable bunch, but the one thing we all concur on is the brilliance of this novel.

- Nothing short of remarkable. Frederick brings it all together in this nonfiction account of how an American platoon’s war crime came to be in 2006 Iraq, and the harrowing aftereffects of it. Unquestionably one of the best works of journalism to emerge from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, The New York Times Book Review compared it to In Cold Blood, with one crucial difference: Black Hearts is all true.

- Grant seems to be in the midst of a reputational rehab, something anyone who’s spent some time with his memoirs–written as he was dying from throat cancer–should appreciate. Grant writes with a direct sort of eloquence, and the chapters about his time as a junior officer in the Mexican War remain a fascinating case study for anyone interested in military leadership.

- World War I prose is its own canon, one that has shaped and reshaped literature for generations. Quite simply, Graves’ autobiography is the very best offering from this canon, with potent self-awareness laced into every sentence.

- I know, I know. This guy. But there’s something so prevailing about Robert Jordan finding justness, perhaps even justice, in the midst of rampant unjustness and corruption. Jordan isn’t interested in long-distance moralizing, or easy pronouncements. He’s interested in channeling hope and idealism into something real and meaningful. I know I found strength in these pages during my own Iraq tour. Now, about Maria’s hair …

- While detailing the influenza outbreak of Denver in 1918, “Pale Horse, Pale Rider” concurrently captures all the waste and horror of the World War I trenches half-a-world away: “No more war,” Porter wrote, “no more plague, only the dazed silence that follows the ceasing of the heavy guns; noiseless houses with the shades drawn, empty streets, the dead cold light of tomorrow. Now there would be time for everything.”

- The decline of the Austro-Hungarian empire as lived through one tragically flawed family, Roth’s magnum opus is part political novel, part sweeping epic, and part elegy to an old world and forgotten vision.

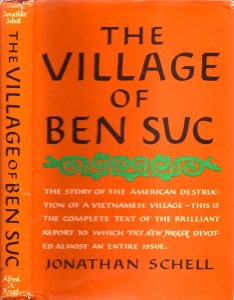

- A devastating (and devastatingly thorough) examination of how a Vietnamese village/Vietcong supply center was systematically razed by the U.S. military; both a how-not-to-counterinsurgency manual and a classic piece of war reportage.

Matt Gallagher

Matt Gallagher is a Wake Forest graduate and US Army veteran. He’s the author of the novel Youngblood and memoir Kaboom: Embracing the Suck in a Savage Little War. He holds an MFA in fiction from Columbia and has written for The New York Times, The Atlantic, Esquire, and The Paris Review. He lives with his wife and son in Brooklyn.