Meet the Writer Who Chased Eve Babitz All Over Hollywood

How Lili Anolik Finally Got Her Subject to Talk

Lili Anolik wasn’t planning to write a book about Eve Babitz. The idea was to put together a series of pieces on the scene in 60s and 70s Los Angeles—the film critic Pauline Kael and novelist Joan Didion were two proposed topics—with Babitz, a lesser-known but cultishly-adored contemporary of theirs, acting as a binding thread between essays, rather than as the book’s subject and central figure.

But then, as seems to happen whenever Babitz gets involved in something, “Eve took over,” Anolik said.

And the next thing she knew, she was writing a biography.

Or not a biography, exactly—not a traditional one, anyway. Hollywood’s Eve: Eve Babitz and the Secret History of LA eschews “facts, dates, timelines, firsthand accounts, verifiable sources,” Anolik writes in the book’s introduction. Instead, what follows is “a psychological commentary, a noir-style mystery, a memoir in disguise, and a philosophical investigation as contrary, speculative, and unresolved as its subject.”

If you aren’t familiar with the subject, a super-quick primer: Eve Babitz was born and raised in LA; she grew up in a world equally informed by her parents’ East Coast intellectualism (Igor Stravinsky was her godfather) and her hometown’s Hollywood glamour. She worked as a visual artist in the 60s and 70s, designing album covers for artists like Linda Ronstadt and Buffalo Springfield, before publishing a handful of books—short story collections and novels, all of them autobiographical works about busty LA girls animated by Babitz’ inimitable voice, at once delightfully breezy and razor-sharp.

“I was so ardent, and I was so crazed. I read the book and I just chased her. I pursued her for years.”

Then, in 1997, a freak accident—a lit cigar, a convertible with the top down, a highly flammable skirt—left her with half of her body covered in third-degree burns. Babitz stopped writing and retreated from public life.

Anolik played a major role in bringing her back into the literary consciousness by profiling Babitz for Vanity Fair in 2014. Several years earlier, Anolik had read a copy of then out-of-print Slow Days, Fast Company, Babitz’s second book, and became obsessed with her style, which she describes as “sort of loose and slang-y, but also really elegant.”

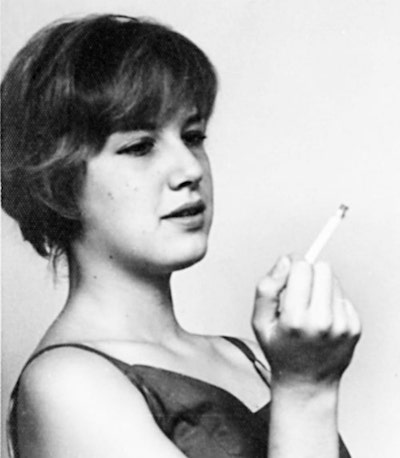

Photo by Mae Babitz, courtesy Mirandi Babitz.

Photo by Mae Babitz, courtesy Mirandi Babitz.

Biographical sketches of Babitz often focus on her relationships to sex and celebrity—in addition to her work making album covers for musicians, she also slept with a lot of them, including a young Jim Morrison—and while that’s certainly part of her appeal, that’s not hardly all of it. Anyone can write a groupie memoir, but Babitz’s books are far more than good gossip. For Anolik, reading Slow Days, Fast Company felt like seeing someone “invent a form,” she said; it was an amalgamation of essay, short story and novel that felt like nothing she’d ever read before. She had to talk to Babitz.

It would take her some years to convince Babitz of that.

The interview Babitz gave Anolik for Vanity Fair was her first in decades. Anolik said she got Babitz to talk to her by dint of sheer, pigheaded persistence. “I was so ardent,” she said of her attempts to make contact. “I was so ardent, and I was so crazed. I read the book and I just chased her. I pursued her for years.”

Anolik wrote Babitz postcards; she got close with her younger sister, Mirandi, and her cousin, Laurie Pepper, as well as her ex, Paul Ruscha (Ed’s brother). She made herself part of Eve’s world so insistently that eventually, Eve accepted her, and even opened up to her. Now, six years later, they talk on the phone regularly. Anolik calls Babitz “Evie.”

“It is exploitative. She was exploiting herself all along; exploiting her sisters. Art is barbarous. The only way I can justify what I did is that I did it with love.”

That intimacy could have introduced complications into the writing process. Biographies are a tricky proposition: they encourage exactly this type of intimacy with your subject, and then, just when you feel that you know them, that they trust you, you have to turn around and expose them: all those soft, squishy vulnerabilities and least-flattering angles displayed for a much less-invested, less sympathetic world to see and judge.

But Babitz would have had a better sense than most of what she was in for by agreeing to be someone else’s subject. After all, her fiction was highly autobiographical; she used both herself and her friends and lovers as her characters. Discussing this practice, Anolik writes in Hollywood’s Eve: “For Eve, though, [Paul Ruscha] was material, to do with what she chose. And looked at from a certain angle, her art—all art—is a form of exploitation, and totally and utterly barbarous, as amoral as it gets.”

Does she view her own writing—especially when she’s writing about Eve, her idol—the same way?

Absolutely. “You can’t get away from that,” Anolik said of what she calls “the exploitation question.“ “It is exploitative. She was exploiting herself all along; exploiting her sisters. Art is barbarous. The only way I can justify what I did is that I did it with love.”

Well, and also, “she let me do it, too. There’s a complicity there,” between biographer and subject, artist and muse, “because she let me in.”

It probably doesn’t hurt that Babitz evinces a deep disinterest in Anolik’s writing about her, as well as all of the legacy-building hoopla surrounding her now, twenty-some years after her books fell out of print and it seemed that her name would be mostly forgotten. “I think she regards all of this,”—“all of this” being Anolik’s work, as well as the reissues of Babitz’s catalogue and various television adaptations in the works—“with a mixture of dismay and a lack of concern,” Anolik said. After all, Babitz already came close once before—her books gained some notice, but never achieved breakout critical or commercial success.

But Babitz did read Anolik’s Vanity Fair profile, which elicited rare direct contact from her. (Usually Babitz calls an intermediary, her sister or Pepper or Ruscha, and has them alert Anolik that she’d like to talk.) “I had been out, and there was a message,” Anolik said of her response. As indifferent as Babitz is to any actual person’s reaction to her, she was still delighted to be portrayed as a provocateur. “She’d obviously started talking before the beep,” Anolik said, “and she just said, ‘Thanks for getting in the story about the blow job.’”

Zan Romanoff

Zan Romanoff is a full-time freelance writer and the author of the novels A Song to Take the World Apart, Grace and the Fever, and Look. Her essays and journalism have appeared in print and online in Buzzfeed, The Cut, Eater, GQ, The LA Times, The New Republic, and The Washington Post, among other outlets. She lives and writes in LA.