Meet the Kobold, the Gnome’s Tougher, Meaner Cousin

Nikki Van De Car on the Many Types of Mischievous Household Spirits

Kobolds are difficult to classify, as they are shape-changers, household faeries, seafaring explorers, and miners. They are described in both Seelie and Unseelie ways, depending on their mood and circumstances, and they have been around for a long, long time. And yet for all that, apart from modern-day interpretations used mostly in Dungeons & Dragons, there has not been much art created of them.

Of course, this could be because while kobolds of all kinds appear to have the ability to change their shape, they typically choose to simply remain invisible and generally do not like it when you try to catch a glimpse of them. However, when they do appear, they can be brownie- or dwarf-like or take the shape of various animals, including cats, bats, chickens, snakes, and worms. But certain kobolds known as drakes may appear as fiery dragons, which can fly through the air like stripes in the sky. They may enter and exit a house through the chimney, and when they do appear as human-shaped, they will wear red jackets.

Like most household faeries, kobolds perform their services in the dead of night, but they are known to set a sort of test for families before they decide to take them on: they will add dirt to the milk jugs and sprinkle sawdust on clean floors.

Now, one might suppose that to pass this test you would need to clean up after the kobold, but not so—you should drink the dirty milk and leave the sawdust in place to show you know the value of the kobold’s work and would suffer without his assistance. Leave a portion of your evening meal for the kobold, and he may well decide to live with you indefinitely, unless you insult him.

But this is a bit of a sticking point, because insulting a kobold carries a far greater penalty than it would with any other household faerie.

But this is a bit of a sticking point, because insulting a kobold carries a far greater penalty than it would with any other household faerie. Brownies or domovoi might trash your house, but kobolds are far more bloodthirsty. Folklorist Thomas Keightley tells the tale of a kobold named Hödeken who was insulted by a kitchen boy who kept spraying water at him. He demanded restitution from the head cook of the household, who refused, claiming it was innocent childish mischief. That night Hödeken tore the boy to pieces and added him to the stew, and then when the cook chastised him, he killed the cook in turn. Hödeken’s reaction wasn’t even unusual or unexpected for a kobold, so you might want to think carefully whether their help around the house is worth the risk.

Another famous (and much more tolerant) household kobold was Heinzelmann, who dwelled in Hudermühlen Castle in Germany. He took the form of a charming boy with curly blond hair and a red silk coat, though he was hardly ever seen—indeed, when a maidservant asked if she could see him, he warned her she would be terrified. She insisted, and he told her to appear at a certain place at a certain time and to bring a bucket of water. She obeyed, and there Heinzelmann was—a charming young boy, with a knife stuck through his back.

As drawn by Willy Pogány (1882–1955), Heinzelmann is small and laughing, delighted with his own joke, and he used the bucket of water to wake her up after she fainted. As kobolds go, Heinzelmann was more harmless than most, going about his business protecting the castle from giants and dwarves and keeping the staff updated on faerie gossip, as well as protecting the chambermaids from unwelcome attentions from visiting noblemen. (Even he had his temper— when a visiting nobleman wouldn’t drink to his health, Heinzelmann dragged him to the ground and choked him, though not to death.)

Eventually the lord of the castle took an interest and sent a message requesting an audience with Heinzelmann—who thought that was hilarious and whispered in his ear he had been there all along, dulling his razors whenever the lord was annoying.

Most kobolds do not have such high-quality living situations, but instead dwell in the hearth, the woodhouse, or in the stables.

The lord didn’t much care for that, which of course only made Heinzelmann want to irritate him further. He followed his lordship around the house, singing the same song all day, every day:

If thou here wilt let me stay,

Good luck shalt thou have alway.

But if hence thou dost me chase,

Luck will ne’er come near the place.

Even sage advice given in an annoying manner will eventually be ignored, and the lord at last was driven out of his own house. He set out in his carriage, but a little white feather (which was, of course, our dear kobold) danced above his horse’s heads, distracting them the whole journey.

And when he arrived at an inn, Heinzelmann continued to bedevil the lord until at last they came to an accord: if the lord would only offer his respect and friendship, Heinzelmann would be a good friend to him. And so a room in the castle was set aside just for him, and he always had a dish of new milk and wheaten crumbs to eat in the morning so Heinzelmann continued to provide his services.

Most kobolds do not have such high-quality living situations, but instead dwell in the hearth, the woodhouse, or in the stables. A biersal, a type of kobold who lives in a brewery, pub, or inn, will sleep in the cellar and in exchange will clean the tables and wash the bottles, glasses, and kegs. Hödfellow lived at Gremlin’s Brewery in England, and he would either help or hinder the workers depending on whether they gave him his fair share of beer, while Alrûn, who could carry a load of rye grain in his mouth despite standing only a foot tall, was happy to work hard so long as he received biscuits and milk.

A sea kobold is much like a household kobold, only he lives on a boat. He is a klabautermann and will help prevent a ship from sinking. That said, if the ship is on its way down, the klabautermann is going to leave the humans behind to fend for themselves, and if the captain of the ship sees one (unlikely, since they are usually invisible) before the ship leaves the dock, he may well delay the journey, as this is thought to be a bad omen.

When they are seen, they are small humanoid figures wearing yellow sailor’s hats and red or gray jackets, and they often enjoy smoking pipes. They will pump water from the hold, arrange cargo, and repair holes. It’s thought they enter the ship through the wood used to build it, and they will continue to help the crew so long as they are treated with respect—and so long as the ship isn’t about to sink, of course. Sometimes captains would provide space in their luxurious cabins for the klabautermann to sleep and share food and drink from their table.

When danger is near, they will knock rapidly and loudly. They don’t like whistling and will throw handfuls of small rocks at you if you do so absentmindedly.

Known as knockers in England, kobolds also live in caves and mines and make knocking noises directing human miners where to dig. When danger is near, they will knock rapidly and loudly. They don’t like whistling and will throw handfuls of small rocks at you if you do so absentmindedly. It’s best to leave some food for them as an offering to thank them for their assistance.

According to Spiritualist Emma Hardinge Britten (1823–1899), who received the description from someone (presumably a client) named Madame Kalodzy, they appear as: “a small human figure, black and grotesque, more like a little image carved out of black shining wood, than anything else I could liken them to…we were so awestruck yet amused at these comical shapes, that we could not move or speak until they themselves seemed to flit about in a sort of wavering dance, and then vanish, one by one.”

Subterranean kobolds work at their own pace in the mines, about their own business. They have their own drilling, hammering, and shoveling to do, and some legends say they are of the rock in the same way sylphs are of the air. Indeed, according to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust, the kobold is the representative of the element of earth, and not the gnomes, as Paracelsus would have it:

Salamander shall kindle,

Writhe nymph of the wave,

In air sylph shall dwindle,

And kobold shall slave.

Who doth ignore

The primal Four,

Nor knows aright

Their use and might

O’er spirits will he

Ne’er master be.

Kobolds can just as often decide to be harmful, however, causing accidents, cave-ins, and rockslides for reasons of their own. (Perhaps they are protecting their own veins of silver or gold? Or something else entirely?) They are also known to trick miners into quarrying worthless ore, following veins of what appears to be copper or silver, but when smelted, is found to be without value or, worse, poisonous. Cobalt, which can cause a burning sensation when handled, was one of the most common of these and is named for the kobold.

Kobolds were mysterious, and yet they were welcomed, as one welcomes an entity one cannot fully understand or predict but does not wish to offend.

Still, kobolds have a tendency to be at least as helpful as they are hurtful, and medieval Germans would carve kobold effigies for their homes in the pagan tradition of worshipping household gods. These might be made from boxwood and wax or from mandrake roots, and the wild kobold would dwell in them when he chose. Kobolds were mysterious, and yet they were welcomed, as one welcomes an entity one cannot fully understand or predict but does not wish to offend.

In the story The Little White Feather, a kobold tells a passing traveler who asks an innocent question:

“Why? How like the child of mortal man! Everything has to tell its reason—you rob the peach of its velvet bloom that you may find the secret of its ruddy splendor and the fairy gems on the grass at dawn are to you but water distilled from earth! You would know how the tide finds a way to turn, why the light of the stars transcends your rush-lights! Elves and Fairies and such-like are driven away by your curiosity.”

We should perhaps listen to this kobold and allow for a little more mystery in the world.

__________________________________

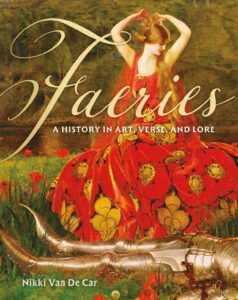

From Faeries: A History in Art, Verse, and Lore by Nikki Van De Car. Used with the permission of the publisher, Running Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group. Copyright © 2025 by Nikki Van De Car.

Nikki Van De Car

Nikki Van De Car is a blogger, mother, writer, crafter, and lover of all things mystical. She is the author of ten books on magic and crafting, including Practical Magic and The Junior Witch’s Handbook, and the founder of two popular knitting blogs. Nikki lives with her family in Hawaii.