The 2019 National Book Awards in Young People’s Literature, Translation, Poetry, Nonfiction, and Fiction will be announced on Wednesday, November 20th at the 70th National Book Awards Ceremony and Benefit Dinner, hosted by LeVar Burton, at Cipriani Wall Street in New York City. In advance of the ceremony, we caught up with (almost) all of the finalists to ask them a bit about their books, their reading habits, and their writing lives. Meet them below!

YOUNG PEOPLE’S LITERATURE

Randy Ribay, author of Patron Saints of Nothing (Kokila / Penguin Random House)

Who do you most wish would read this book?

I wrote with Filipinx American teenagers as the primary audience in mind. When I was that age, I was starting to grapple with what that hyphenated identity meant. On one hand, I didn’t feel American enough; on the other, I didn’t feel Filipino enough. Despite the significant population of Filipinos in America (we’re the third largest immigrant group in the US), we’re woefully underrepresented in media. I never encountered a book or movie that reflected this struggle specifically in the FilAm context that could help me make sense of it until college. I hope Patron Saints of Nothing reaches Filipino American teenagers so they can start asking questions and making their own sense of their identity.

How did you navigate writing about a topic of such brutal violence for a relatively young age group?

I heard Jason Reynolds say once that our job as writers for children is to prepare them from the world, not protect them from it. This really resonated with me and articulated so succinctly my own approach that now I like to steal his response when asked this question. The world is the world. Brutal violence is part of it as much as love is part of it. Despite what we might hope, most kids already know this. They come across this truth either in the news or in history class or in their own lives, etc. Ignoring that brutality or trying to shield kids from it simply sends the message that we should pretend these things don’t happen and that we should stay silent about them. This turns kids into adults who either ignore tragic events or who are overwhelmed by despair—and we’ve already got more than enough of those. Instead, it’s vital to give kids safe spaces to begin to honestly confront the reality of things like the Philippines’ brutal war on drugs so they are better prepared to react to them. A book can be that safe space where they can read about a kid their age also learning about and processing this kind of stuff. In turn, I believe this helps kids figure out how to process these realities in a healthy way.

If you have a day job, what is it? How do you negotiate writing and working?

I’m a full-time high school English teacher. By the end of the day, my mind is either too exhausted or too filled with what happened over the course of the day or with papers I need to grade, so I write early in the mornings. I’m fairly disciplined about writing from about 5:00 am to 6:30 am every weekday. It’s not a lot of time, but I can usually get in 500-1000 words in that window, and it adds up day by day. I also have to be judicious about which festivals and events I attend. I try to miss as little school as possible, and traveling too many weekends in a row can get exhausting.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I stick with my set writing routine, even if I’m getting only a few sentences down in the same amount of time I usually get a few pages. I try to accept that that’s how it goes, that my own writing energy ebbs and flow. Every word counts, and I’ve been through this enough to know that I might have a couple weeks of low word-count days before getting back to usual. But what I end up writing on the other side wouldn’t have existed if I didn’t write those handful of words when I was really struggling to get anything out. Reminding myself of this prevents me from beating myself up or giving up. Beyond that, I might also do additional research or take some time outside of my writing window—like when I’m walking my dogs or biking to work—to try to identity and think through potential story problems. Because sometimes I find what’s causing the block is an issue like not understanding one of my characters enough or falling into a plot hole.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

I’m an English teacher, so I end up literally going back to a lot of books over and over (and over) again, but in my free time I’m not a big re-reader. I do go back to the Harry Potter series every few years because I love that world and those characters so much that rereading them feels as safe and relaxing as handing out with old friends.

What’s the best book you read this year?

It’s too difficult for me to narrow it down to one, so I’m going to cheat. Of books that were published in 2019, I really loved SHOUT by Laurie Halse Anderson, Pet by Akwaeke Emezi, Forward Me Back To You by Mitali Perkins, Look Both Ways by Jason Reynolds, The Downstairs Girl by Stacey Lee, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong, In Waves by AJ Dungo, and Trick Mirror by Jia Tolentino. In terms of pre-2019 books that I’ve read recently, some of my favorites have been The Night Diary by Veera Hiranandani, Hey, Kiddo by Jarrett Krosoczka, The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller, There, There by Tommy Orange, and the Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy by Cixin Liu. I’m probably still forgetting several . . .

*

Martin W. Sandler, author of 1919 The Year That Changed America (Bloomsbury Children’s Books)

Who do you most wish would read this book?

I would like as many young people as possible to read this book because developing a sense of history at from an early age is so important. I would love to help young readers realize that the truth can be even more exciting and surprising than fiction.

What’s the best book you read this year?

Right now I’m reading Baseball in 41 by Robert Creamer—it’s preliminary research for a new book idea I’m contemplating. It’s so beautifully and engagingly written that I’m having trouble putting it down.

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

My wife, Carol. We’ve been together for more than 45 years, and she’s been a huge part of all of my work. Anytime anything of any magnitude happens she’s the first person I share it with.

What time of day do you write?

Writing a book is my most pleasurable activity. I write seven days a week, at any time of day, between eight and ten hours a day.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I don’t get writer’s block, and the reason is that I’ve discovered that writing’s not about inspiration, it’s about perspiration. I work very hard, and if I’m not where I want to be yet, I just keep going. I don’t ever leave my desk until I know I am set up for the next session.

What’s the trick for writing engaging history aimed at young readers?

First and foremost, you never, ever write down. You have to respect young readers’ perceptions, inquisitiveness, and their intelligence—which is far greater than most people give credit. The other trick is to make the book as engaging as it is informative. History should never, ever be dull.

*

Jason Reynolds, author of Look Both Ways: A Tale Told in Ten Blocks (Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books)

Who do you most wish would read this book?

The real Ms. CeeCee. She was the neighborhood candy lady, and also my babysitter. I would love for her to read this just so she could laugh and laugh and laugh, because she remembers the kids many of these stories are based on.

What’s the best book you read this year?

The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

Craft. I love to talk craft, but rarely get a chance to do so.

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

My agent. It should’ve been my mother, but she was at work and wouldn’t have been able to answer the phone.

What time of day do you write?

Early in the morning. I start around 7am, simply because I feel like my brain is buzzing at that time. Around 2pm, I pretty much slip into an almost laughable sloth.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I write badly.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

Jesmyn Ward’s Salvage the Bones, Jean Toomer’s Cane, the opening poem of Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony. This list could go on for a while, so I’ll just stop there.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Song. Could you imagine a life without Stevie Wonder?

If you have a day job, what is it? How do you negotiate writing and working?

I don’t have a day job. And now I feel like a jerk.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

That when it comes to writing, my intuition will take me farther than my education ever will.

*

Laura Ruby, author of Thirteen Doorways, Wolves Behind Them All (Balzer + Bray)

Who do you most wish would read this book?

Frances Ponzo Metro, my late mother-in-law, whose early life inspired this book. She read an old draft some years ago, but she died before she could hold the book in her hands.

What’s the best book you read this year?

Since I’ve been writing a lot of fiction, I’ve been reading a lot more non-fiction and memoir, graphic novels and poetry. I adore Mira Jacob’s graphic memoir Good Talk, told in often hilarious, sometimes heartbreaking “conversations” about race and identity, love and family. The mix of dialogue, illustration and photography is so inventive. And I’m savoring every word of Anne Boyer’s memoir The Undying, which is bracing and furious and real and unlike any cancer memoir I’ve read before (and I’ve read a lot of them since I was diagnosed in 2017).

What time of day do you write?

Though I am not a morning person, I write in the morning as early as I possibly can. It takes a while for my cranky inner critic to wake up, and the more words I get in before she starts going on about how I’m an idiot and a fraud and a hack, the better.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I put on loud music and dance with my cats. (Or rather, I dance while my cats wonder if I’m okay). I take a lot of walks and even more showers. So many showers. I’m very clean.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

It’s a toss-up between Pride and Prejudice and We Have Always Lived in the Castle. I love the idea of a Jane Austen/Shirley Jackson mash-up. We Have Always Lived at Pemberley. The Haunting of Kellynch Hall. Hmmm. Maybe I’ve found my next project.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

The best writing advice I ever got was from a teacher I had in high school. She told me to stop doing it because I simply wasn’t very good. Let’s just say I took that as a challenge.

Also a finalist: Akwaeke Emezi, author of Pet (Make Me a World)

POETRY

Arthur Sze, author of Sight Lines (Copper Canyon Press)

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

My wife, Carol Moldaw.

What time of day do you write?

I like to write early in the morning when it is still dark. As the sun rises, I see forms emerge out of the darkness. And as daylight brightens, I try to catch that physical wave in my writing.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I turn to translation. Writing out the characters of an ancient Chinese poem and then translating it into English is a way of working with language that can ease the difficulty of figuring out what to write next.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

Two books I return to again and again are Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu, translated by Burton Watson.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

When I was an undergraduate at the University of California at Berkeley, I audited a month-long fiction writing class taught by Lillian Hellman. One day, in her office, she said to me, “I don’t know anything about poetry, but I advise you to write and never stop writing; if you stop writing for even three months, you will lose all the momentum with language you are developing.”

*

Toi Derricotte, author of “I”: New and Selected Poems (University of Pittsburgh Press)

What’s the best book you read this year?

Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom by David W. Blight

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

The spiritual nature of writing poetry.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

William Carlos Williams, all books; Rilke, Duino Elegies.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

All of Billie Holiday, especially “Deep Song.”

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

“Speak the unspeakable.” Galway Kinnell.

*

Ilya Kaminsky, author of Deaf Republic (Graywolf Press)

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

My wife, naturally.

My cat was the close second.

What time of day do you write?

I have long ago sold my soul to the gods of night-writing. There is a strange freedom in the night hours, when the images of the day go neatly to sleep in each other’s laps, when you stand alone, naked, before the page, and the night is your only defense & comfort.

Night is especially helpful when one is working on a book long sequence.

That solace-isolation of the night when it is just you, you alone, you very alone: and the world of your book.

As for day time: it is the realm of notebooks, the realm of random lines.

So as the day begins: the lines find their way on paper whether I overhear two boys insulting each other at the gas station, or see a gull cleaning her feet, or two old men playing dominoes on a hood of a car, or two young women kissing at the fish market. They become lines on receipts, on my hands, on a water bottle, on other people’s poems. Lines collect for years, but once in a while they discover that other lines are sexy and, well, the poems may come from that sort of a relationship. If I am lucky. Which isn’t often. But one has to have faith.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

There are so many other things in life! I translate, edit anthologies, wash the dishes, entertain my cat, and try not to disappoint my wife. Or, I write letters to friends about their poems. My friends are so prolific! There is always a manuscript to read and give comments on and play ping pong with. And, it is such a wonderful thing—to be reading your friends’ book-drafts, to be in conversation, to polka inside their heads, mind to mind. What a privilege.

And then, of course, when poems go on vacation, why not pay a visit to an essay?

After all, an essay is a kind of place that loves a lonely visitor with a hat in hand.

Which books do you return to again and again?

In no particular order, the dead writers that come to mind this morning: Shakespeare’s Lear, Pushkin’s Evgenii Onegin, Dickinson. Brooks. Ovid’s Metamorphosis. Akhmatova. Hayden. Mandelstam. Clifton. Issa. Paley. Celan. Cesaire. Edmond Jabes. Morrison. Ritsos. Gilgamesh. Christopher Smart. Pasternak. Anna Kamienska. Wang Wei. Hopkins. Zbegnew Herbert. Tsvetaeva. Weil. Vallejo.

Ah, and, also, for me: Gogol & the hordes of East European fabulists. Why? I realized early on that by temperament, I am not a documentary poet; I am a fabulist.

And, yet, the world pushes through, the reality is everywhere in this fable.

My job is to make this border between the shelter of fable and the bombardment of reality a lyric moment, I feel.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Ha! Is there time? I am afraid that as an immigrant I am always one foot in another literary culture altogether.

See, I wrote verses in Russian for quite some time before we came to America. When we came to this country, I was sixteen years old. We settled in Rochester, New York. The question of English being my “preferred language for literature” would have been quite ironic back then, since none of us spoke English—I myself hardly knew the alphabet. But arriving in Rochester was rather a lucky event—that place was a magical gift, it was like arriving to a writing colony, a Yaddo of sorts. There was nothing to do except for writing poetry! Why English then—why not Russian? My father died in 1994, a year after our arrival to America. I understood right away that it would be impossible for me to write about his death in the Russian language, as one author says of his deceased father somewhere, “Ah, don’t become mere lines of beautiful poetry!” I choose English because no one in my family or friends knew it—no one I spoke to could read what I wrote. I myself did not know the language. It was a parallel reality, an insanely beautiful freedom. It still is.

Is it an escape into another medium?

Well, there is a beauty in falling in love with a language—the strangeness of its sounds, the awe of watching the sea-surf of a new syntax beating again and again the cement of your unknowing. Learning to speak again can be erotic—the unfamiliar turn of the tongue, the angle of the mouth, the movement of lips.

On the other hand, you are so powerless, so humbled, so lost, bewildered, surrounded by nothing but your own confusion. That, too. You don’t know the word, what to do?

And then: the miracle of metaphor. You know other words, they come to redefine what you wanted to say in the first place, you see the world slightly differently from where you began, your mouth makes sounds you didn’t know were possible.

What changes? Even the shape of my face changed when I began to write in English language.

As for non-language things, there are wonder-plenty: Ice skating! Cooking! Dancing at gas stations!

*

Jericho Brown, author of The Tradition (Copper Canyon Press)

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

I really just want to say that—though it’s one of our biggest fears—writing is not a narcissistic act because what we do is work in the production of beauty. Our relationship to trees is a relation to beauty. If we don’t think people who plant trees are narcissists, we can’t think people who make poems are narcissist. On the contrary, poets are the people who help to make this world livable in the same way that trees have something to do with the fact that we breathe.

What time of day do you write?

I probably do my best work very late at night when it is dark and the world has gone to sleep and there’s no chance of being distracted.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I don’t know what this is. I’m a poet by identity. This means I’m writing all the time. Writing is the way I think. It is not just typing. Most of the writing happens in the mind. I’m not a poet because I have poems; if anything, I feel a little less alive once a poem is done as I don’t know that another will be on the way. I’m not a poet because I’ve written poems. I’m a poet because I write poems, and I’m writing them even as I write the answer to this question.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

I wouldn’t have been able to finish The Tradition if I hadn’t seen Moonlight. I really changed how I could better see myself. I say more about it here.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

“Never say no.” –Nikki Giovanni

*

Carmen Giménez Smith, author of Be Recorder (Graywolf Press)

Who do you most wish would read this book?

I’d be thrilled if the long poem in this book was projected through megaphones in front of the White House.

What’s the best book you read this year?

Ordinary Beast by Nicole Sealey.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

At some point I’d like to talk about the long influence that the music I love and have listened to over the years has had with my poetry, sometimes in very surprising ways.

What time of day do you write?

I write very late at night because the dark keeps me from distraction, which is a big pitfall to me. Distraction could be anything from a picture askew on the wall to a pile of laundry.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I have a set of exercises that I do to generate work like copying a syntax from another poem or reversing the words of another poem, but I also don’t try to hunker down with a single piece of writing, so if I lose steam with one poem, I move on to another one.

LITERATURE IN TRANSLATION

Yoko Ogawa and Stephen Snyder, author and translator of The Memory Police (Pantheon)

What time of day do you write?

YO: In the morning. Whether or not the day is a success depends on how much I’m able to write in the early hours. As soon as I wake up, I sit down with the novel I’m writing. Before taking a walk, reading the newspaper or any other excuse to procrastinate presents itself, I enter the world of the story.

SS: In the interstices. My job with the Middlebury Language Schools keeps me busy.

How do you tackle writer’s (or translator’s) block?

YO: By just writing. Even when I can’t write, I write.

SS: One pleasure of translating is that “translator’s block” isn’t really a thing. Someone else has already suffered through the doubts and questions that can upend the writing process. Translators encounter puzzles and obstacles, but they’re the kind that can generally be resolved with enough effort.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

YO: Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl. It’s the book that first taught me that the act of expressing something in words can free a human being.

SS: Anything by John Ashbery or Elizabeth Bishop.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

YO: Musicals. The moment when you enter the theater with a ticket to a musical in your hand is a moment of irrational joy.

SS: Korean ceramics. The early Neil Young.

What has your experience being translated (or translating this book) been like?

YO: It’s the experience of seeing off a child who is leaving on a long journey.

SS: An enormous pleasure. Despite the prevailing darkness, it’s a luminous book with many moments of intense beauty, and the clarity and precision of Yoko Ogawa’s prose is a joy. Translating it felt like a natural, organic process, something that was necessary.

*

Khaled Khalifa and Leri Price, author and translator of Death is Hard Work (FSG)

Who do you most wish would read this book?

KK: Everyone, especially my childhood bully.

What’s the best book you read this year?

KK: The River of Gold in Aleppo’s History and a history book about Aleppo’s history in three volumes, by the historian Sheikh Kamel Al Ghazi.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

KK: Remorse.

LP: Imposter syndrome. Also: respect trans people, they know best what gender they are/n’t and let’s all stop obsessing about what’s in their underwear.

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

KK: Yasmina Jraissati, my guardian angel.

What time of day do you write?

KK: From 12 to 5 o’clock in the afternoon.

How do you tackle writer’s (or translator’s) block?

LP: I cook something. Lasagna is good, but baking a cake also works well. It’s so satisfying to do something that has a tangible result, and it seems to melt the frustration that is cause and effect of being blocked. Plus, you get to eat cake afterwards.

If the writer I’m translating mentions music in their books, then I try going for a walk and listening to that music as well. Khaled is particularly great for this.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

KK: All of Dostoevsky’s books.

LP: It changes from year to year, but at the moment it’s The Diary of a Provincial Lady by EM Delafield. I could say that it is a study in how to sound effortless, but honestly it’s just so funny and charming. I also enjoy regular visits with my close personal friends in A Suitable Boy by Vikram Seth. It’s my talisman during the familiar discussions with editors about the amount of Arabic words left in English translations. Unfamiliar words aren’t scary, they’re exhilarating and poetic and they communicate regardless.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

LP: Kirsty Merryn’s “Bring Up the Bodies.” I used to sing and drum this to my daughter when she was a baby and it was like a magic charm to stop her from crying. (Admittedly, now she’s old enough to understand the words it might have the opposite effect.) That whole album is the soundtrack to some of my most precious memories.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

KK: Don’t ever listen to advice and try everything you can.

LP: Read it out loud. And go for walks—writing (and translating) don’t happen solely in front of a computer screen.

What has your experience being translated (or translating this book) been like?

KK: Beautiful, with my lovely translator Leri Price.

*

Scholastique Mukasonga and Jordan Stump, author and translator of The Barefoot Woman (Archipelago Books)

Who do you most wish would read this book?

JS: I’d like this book to be read by anyone who dismisses the humanity of others.

SM: I would like Salaa Saleh to be able to read my book. She’s a young woman in Khartoum, Sudan who stood up against dictatorship—she’s known as “the girl in white.” For the sake of her people, she fights for liberty, democracy and justice. I read on the internet that she sees herself as a successor to the Kandaka, the Nubian queens who reigned long ago over the ancient kingdom of Meroë. My mother Stefania also drew on tradition to save her children.

I will also dedicate my book to all female resistance fighters. I’m particularly thinking of Marielle Franco, who was assassinated in 2018 in Rio de Janeiro. And I’m thinking of her mother, whom I held in my arms, a woman in pain, but a woman of great strength, fighting to expose the truth about her daughter’s assassination and demanding justice.

What’s the best book you read this year?

SM: From this past year, I’m choosing two Toni Morrison books, Beloved and the essay collection The Origin of Others. I’ll add Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates for its fight against the obsession with skin color.

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

JS: My first thought was actually how to get out of telling anyone. It’s a tremendous honor, of course, and I’m delighted in every way, but these things make me a little nervous.

What time of day do you write?

JS: I translate when I can, which is to say that I spend much less time translating than I would like. I teach, so I have to work around class preparations, grading, meetings, etc. At irregular intervals, a little stretch of free time comes along: that’s when I translate. In some perfect world, I would be able to translate or revise for hours at a time, preferably on a cool, rainy afternoon, but I’m not sure that’s ever going to happen.

How do you tackle writer’s (or translator’s) block?

JS: I just force the words out, whether they’re any good or not, sometimes even whether they make sense or not: just force the words out, and then make use of the translator’s most important tool—time—to reread, rethink, rework. Little by little (and in my experience it can only happen little by little) the text will begin to cohere and take shape; but you can’t wait for that to happen, you’ve got to make it happen, and often that means simply forcing it.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

SM: Night by Elie Wiesel and If This Is a Man by Primo Levi are my bedside reading. They were my guides and my supports in the difficult work of memory that was placed on my shoulders by the Tutsi genocide and my family’s massacre. I believe it was a few sentences in Night that made me see how meaning might be given to the fact of having survived, and that allowed me to overcome survivor’s guilt and despair by writing.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

JS: Beethoven’s piano sonatas (all of them). Also Schubert’s. Also Prokofiev’s, and all piano music by Brahms.

What has your experience being translated been like?

SM: My writing comes from a genocide. It’s a story that has questions to ask of all humanity. My mother tongue is Kinyarwanda, yet I write in French. French is my language by pure chance, thanks to the vagaries of colonization. If I had gone into exile in Uganda like many Tutsi, I would probably have written in English. I don’t renounce my adopted language, I feel comfortable in it. Nevertheless, I pepper my writing with Kinyarwanda words to remind you of the origin of my writing. It goes without saying that I would like my books to be translated into every possible language, to liberate them and give them new lives thanks to the talents of translators.

At its heart, I thought, this was a book about motherhood and daughterhood—meanwhile being a moving tribute to the women of the community—what were the challenges of exploring womanhood amidst the horrors of the Rwandan genocide?

SM: The Barefoot Woman is built on memories of my childhood in Nyamata, to which my family and many other Tutsi were deported in 1960. They were exterminated there in 1994. Destiny decided that I would survive, that I would protect the memory of all those who were lost. I cannot describe the horror of the daily persecutions and repeated massacres we endured. But in Nyamata, there was also the life I lived day to day, and a childhood that our parents wanted to be ordinary. I like to describe the works and days of that struggling community in close detail, so as to preserve their traditions against all odds. Many of my readers have told me of the pleasure they find in the ethnological parts of my book. And it’s true that, even living in exile, my mother Stefania, like all Rwandan mothers, strove to salvage and to share all the Rwandan traditions she had learned from her mother. The book is a homage to my mother; now it’s my turn to guard the tradition she passed down to me.

Translations of Mukasonga’s answers by Corinne Segal

*

Ottilie Mulzet, translator of László Krasznahorkai’s Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming (New Directions)

What’s the best book you read this year?

The Silence of the Girls, by Pat Barker. I feel that Barker’s centering of the story of the Trojan wars in the experience of the enslaved women is a genuinely radical gesture. “No words from women in this period survive,” as Emily Wilson put it.

How do you tackle writer’s (or translator’s) block?

I don’t get translator’s block, instead I get translator’s fatigue, meaning that I regularly need to take short breaks to recharge my batteries. Perhaps it is something about following someone else’s train of thought so closely, the sheer intensity of thoroughly inhabiting another writer’s voice. There are times, though, when I’m stuck on a specific problem (for example of wording), and usually the solution to something like that will suddenly pop into my head at quite another time.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

Virginia Woolf’s The Common Reader, her diaries, and in Hungarian, the short stories of Miklós Mészóly, the poetry of Zsuzsa Beney and her critical essays, the poetry of Ágnes Nemes Nagy and her essays, the poetry of János Pilinszky and his shorter prose pieces, the diaries and essays of Imre Kertész.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

There is one particular Mongolian long song, “Dream of Gobi,” that I am very grateful to have heard in my life. It’s on a pentatonic scale, spanning at least two octaves, like most Mongolian long songs. My favorite version is by the singer Chimidtseye (the lyrics are by the poet B. Lhagvasüren). In it, the daughter of a camel herder sings of seeing the moon float by in her cauldron of milk and her mother in a dream (“In a clear dream, I am encircled by my mother.”)

What has your experience being translated (or translating this book) been like?

Uncanny. More than once, when traveling in Hungary (usually to the Translators’ House by Lake Balaton), I found myself encountering one or more of the characters in person. One day I was on a local commuter train to Székesfehérvár, and suddenly, the Professor was sitting there across from me.

Also finalists: Pajtim Statovci and David Hackston, author and translator of Crossing (Pantheon)

NONFICTION

David Treuer, author of The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee (Riverhead)

Who do you most wish would read this book?

I think I was about thirty before I truly felt the power of belonging to a tribe. I had always known, of course, that I was Ojibwe; that I was from the Leech Lake Reservation; that my family was from the small village of Bena on that reservation. I knew it, but I don’t think I felt it. And I think, now, that the raw comfort, the feeling of intense belonging, that came over me later in life had been kept from me, by the idea of what being Native meant dominant in American discourse and dominant in my own mind. I had internalized the idea (among others) of the “disappearing” and disappeared Indian. But once I felt what it meant to belong to tribe, to claim and be claimed by one, I knew I had to write into the face of the idea of our powerlessness. And so—who do I most wish would read this book?—me at 15, 20, and 25; my tribe then and now; and the rest of America now and beyond. Because we need to remember our continued and excellent existence in order know our worth.

What’s the best book you read this year?

Roxanne Gay’s Bad Feminist and Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West (I can’t pick just one).

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

I started writing The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee in January of 2016 the week my father died and in the same month I began dating the woman I’d eventually marry. In ways I’m only really recognizing now I was able to begin the task because of my father’s example and I was only able to finish it because Abi Levis. My father was an immigrant: a Holocaust survivor, he fled Austria and found refuge in America. And he made it his life’s work to find a way to make the troubled country that had accepted him better. We are all responsible for the actions of our country and this being so we all must carry that weight in our own way. My father felt passionately that since America saved him he must do his part to save her, often from herself. It was that belief—in country, in justice, and in Native American communities—that guided him. This book is my own way of trying to make it better. So I wish I could have told him about being a finalist of the National Book Award. And Abi, my wife–while busy with her own brilliant career as an opera singer and her passionate care for her own father–made schedules for me, and cooked for us, and was a patient listener and often a first-reader as the work spooled out of my keyboard. She was the first person I could and did tell.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

Funny thing. I don’t really get writer’s block. Getting the words out has never been the hard part. Sometimes, of course, they don’t come as easily. But I have always loved being edited and have managed to create within myself my own much smaller, much less intelligent editor. So if the words aren’t right I print out the previous chapter and using a pencil I edit. And that usually gets me back on track.

What is one story, fact, or concept from the period of history you cover in your book that you think everyone should know (but most people don’t)?

Just one story? One fact? I suppose the reason I only really write long-form narratives is that I feel crowded otherwise, so it’s terribly hard to pick one thing I hope people know. But if I had to pick I would want to draw attention to Ponca chief Standing Bear. In the late 1870s, after his tribe had been illegally removed to Indian Territory without supplies, his son (along with a third of the tribe) died of starvation. Standing Bear had promised his son he would bury his bones alongside those of his ancestors in present-day Nebraska. As Standing Bear traveled north he and his entourage was arrested and detained. In the eyes of the government he and his tribe lacked even the most basic rights non-citizens and foreign visitors to the U.S. have, among them the right to move freely about the country. In the eyes of the government he wasn’t even a person. Instead of sending Standing Bear back to Oklahoma General George Crook (who had spent a lifetime fighting Indians) gave Standing Bar refuge at Fort Omaha and helped Standing Bear sue the government.

The judge’s decision in favor of Standing Bear ran to eleven pages. It was the first time a U.S. court had recognized the person-hood of an American Indian. And this was after the Civil War. Standing Bear traveled on and buried his son and remained in his tribal homelands in northern Nebraska for the rest of his life. In his story I find so many important things woven together: a terrible history of mistreatment; the passionate hard work of Indian allies like Crook, journalists, and the judge; and the stubborn soulful insistence of Standing Bear that he be allowed to live has he pleased. In this one moment we can see the best and worst of the country and the ability and willingness of American Indians to make their own history and to help steer the country to a better, more humane, place.

*

Tressie McMillan Cottom, author of Thick: And Other Essays (The New Press)

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

The first person was Tara Grove, my editor at The New Press. No one has been my partner in crime more than Tara has been. I’ve said it before, and I suspect I’ll say it for the rest of my life: having a black woman editor who was smart enough to edit me, confident enough to push back, and had enough faith in me to allow my voice to make it through the editorial process, was the difference between this book being filler and being the book that it is today. I wanted her to know that her investment in me and in this project had all been worth it.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I’ve actually never had writer’s block. And I don’t say that to humble brag, although I did choose to answer this question. Are there times when I think I want to write and feel like I should be writing, but I’m not writing? Yes, absolutely, and I think that’s what people mean when they talk about writer’s block. But I understand that experience differently. If I want to write but cannot write, to me it means that I’m not yet ready to write. The way I resolve that is by reading. If I’m not ready to write, it’s because I haven’t finished reading. So I keep reading, and I try to keep experiencing other people’s ideas and experiences until I am once again ready to write. Writing may be work, but it isn’t a job; it will not necessarily conform to the dictates of a 9 to 5. I know many writers say they just sit butt-in-seat every day from 6 a.m.–4 p.m. and that is how they get it done. I can do that, but I can’t do it every day indefinitely and continue to write well. Since I endeavor to write not just a lot or frequently, but to write well, I have to allow time for myself to read and think. It’s just a reimagining of what writer’s block is: not the absence of writing, but rather a part of pre-writing, immersing yourself in lived experiences so you actually have something to write about.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

Great question. I do have a set I’ve kept with me as I’ve traveled through life. When I don’t know what else to do, to read, to write, or I’ve taken in too many other peoples’ voices and need to get back in touch with my own, I always go back to the 20th century African American writers whose work I grew up on. Zora Neale Hurston, Gloria Naylor, Baldwin’s essays… I like to get back in touch with the way that my people speak. The rhythm of our language inspires me. I return to Their Eyes Were Watching God, The Bluest Eye—these are my comfort food books. Bailey’s Cafe, The Women of Brewster Place. To me, they are like reading Psalms in the Bible. You know how they end, and you know what their messages are, but hearing their rhythms takes me back into my comfort zone.

If you have a day job, what is it? How do you negotiate writing and working?

I have four day jobs. I am a tenured professor, I run a podcast with my very good friend Roxane Gay, I’m black, and I’m a woman. How do I negotiate writing and working? Lately, I don’t. I am miserable when I’m not writing or pre-writing or post-writing and worried about pre-writing again, so I don’t go too far away from it, because the people who care about me want me to get back to writing as quickly as possible. When I am writing, I am my fullest self. Maybe not my happiest self, but certainly my most joyful, well-adjusted self. There is no win-win—something always loses when I choose to write—but I make that choice, because writing is important to me. That usually entails clearing my travel schedule, letting my house fall down around me, and calling in reserves to help me stay fed, upright, and human while I work on my craft.

If you could magically insert one fact, argument, or piece of knowledge from your book into every American’s mind, what would it be?

The answer to this depends on the audience. Black people understand structure as opposed to individuals just fine, if only because we understand that there is something bigger than us that shapes our life chances. We know that whiteness exists and that it shapes what’s possible for us. Even though we work really hard not to believe in it, we know it’s there. I wish white people knew that—that there was something bigger than themselves that shaped their life chances. Maybe if they understood class as a function of their own racial identity, they would develop an identity that did not necessitate oppressing other people.

I wish our popular discourse better understood the difference between individual prejudice, racist acts, behaviors, and feelings, and things like systematic exclusion, oppression, and marginalization. Something can be true for a significant number of people and not be true for everyone. Both of those things can happen at the same time and do every day, in fact. That’s one of the great analytical tools we borrow from sociology, though not just sociology. There are other forms of knowledge and knowing something is bigger than the individual self. In the West, our minds don’t hold onto that very well. It’s antithetical to the idea of being American, and I think that’s why we find ourselves faced with a poverty of public discourse about the really big problems that face us as people.

*

Sarah M. Broom, author of The Yellow House (Grove Press)

What’s the best book you read this year?

Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments.

What time of day do you write?

Early morning, around 4 am, before the noise.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

Show up. Stay. On repeat. Ritual and routine.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

W.G. Sebald, The Emigrants. Eva’s Man and Corregidora by Gayl Jones. Everything Toni Morrison ever wrote and I mean everything. Autobiography of a Mother by Jamaica Kincaid. Joan Didion, Political Fictions. Albert Murray, Train Whistle Guitar.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Sonny Sharrock’s “Black Woman.” The art of Whitfield Lovell.

*

Carolyn Forché, author of What You Have Heard Is True: A Memoir of Witness and Resistance (Penguin Press)

Who do you most wish would read this book?

I most wish that this book would find readers among the young Salvadorans who fled to the United States with their parents during the war. It is for them, and others of their generation, who might want to learn about one young woman’s journey to awareness.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

I would like to be able to speak more about the families now fleeing Central America, refugees of war’s aftermath, those seeking asylum with us now.

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

In my heart, I told Leonel Gomez Vides, my mentor and guide, as I was alone when I heard the news, and he is gone, but very much still within me.

What time of day do you write?

I write in the early morning, beginning an hour before the sun, because the world is quiet then, and in that liminal state I can reach more deeply into memory.

What is it about this story that needed to be told in prose rather than poetry?

I always knew that if I were to tell this story fully, it would require the capaciousness of prose—I would have to live through it again, to assemble the thousand memories back into the world, retrace my journey, let the voices of all who were there speak again on the page and come alive. To do that, I did not have to give up poetry, but I had to give the writer in me other freedoms.

*

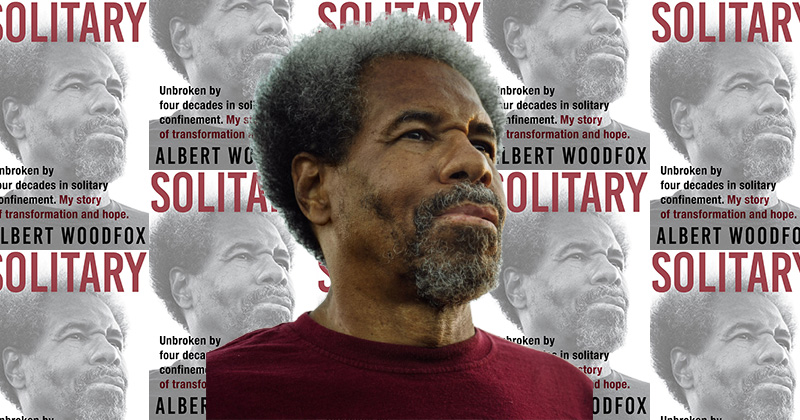

Albert Woodfox, author of Solitary (Grove Press)

Who do you most wish would read this book?

Everyday working-class people. Because I think they can relate to my life and what I’ve had to endure.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

The lack of integrity in political leaders today.

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

Leslie George, who wrote the book with me.

Which book or books do you return to again and again?

A Different Drummer, by William Melvin Kelley, because it is the book that awakened my consciousness.

Which non-literary piece of culture could you not imagine your life without?

R&B music.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

To be honest.

What was it like to bring someone else into the process of sharing your personal story?

It was very painful, because I realized that I would have to relive all the horrible moments of my life through conversation.

FICTION

Susan Choi, author of Trust Exercise (Henry Holt)

What’s the best book you read this year?

Stefan Hertmans’ War and Turpentine. It’s not a 2019 book, but it’s what I read this year that most blew me away.

What time of day do you write?

Morning, because it’s the best time for everything, for me. Unfortunately that means it’s also the best time for me to do everything else.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

When I actually do tackle it, I set a word count goal and don’t let myself get up for lunch unless I’ve met it. But doing that takes resolve, so a lot of the time I don’t tackle writer’s block. I let it win!

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

Alice Munro’s Selected Stories and The Great Gatsby, in both cases for their pacing, all the stuff those authors leave out to get you where they want to get you.

If you have a day job, what is it? How do you negotiate writing and working?

I teach creative writing, which both feeds by own creative writing and erodes it depending on whether I can keep the fine balance between enough teaching—I like teaching—and too much teaching. It’s really hard to do that. It seems to come down to whether or not I can teach and still have whole days of the week where I don’t engage with my teaching at all, but only my own writing. Some weeks yes, many weeks no.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

Write every day. See above for how well I’m doing at this.

Trust Exercise is both an affecting narrative and a thrilling meta-narrative—its form is a huge part of its impact. How did the story evolve in your brain, and did you have any particular literary models for it?

The book evolved over time without, it seems to me, a lot of influence from me. I was primarily working on something else the whole time I was writing TE, and I only returned to TE when I was stuck on the other thing and felt compelled to sneak off, so it was always fun. And, the stakes felt low. I felt as though it didn’t really matter how TE evolved because I wasn’t really writing it. In retrospect I think Jennifer Egan’s The Keep was a clear model—I adore that book—but I wasn’t aware of any models during the actual writing.

How do you feel about Trust Exercise being described as a #MeToo novel?

The completion of this book and the eruption into national consciousness of #MeToo coincided, so it seems inevitable and apt, and I’m grateful a book of mine could be in conversation with something that I think is so important. I also hope the book is large enough to continue to hold that space for #MeToo while connecting with additional sources of meaning, going forward.

*

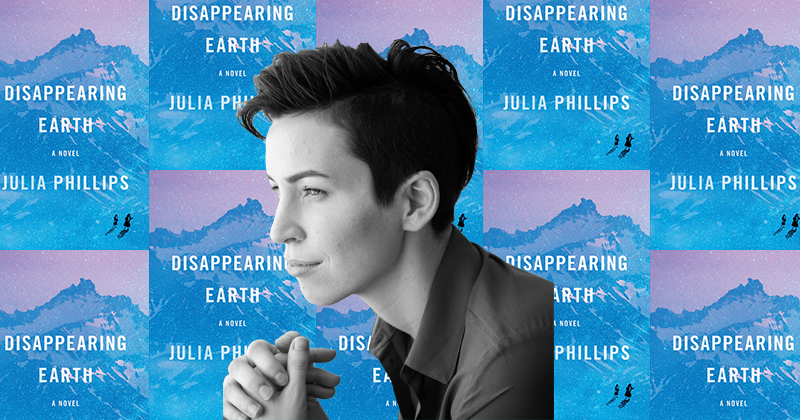

Julia Phillips, author of Disappearing Earth (Knopf)

Who do you most wish would read this book?

I wish my grandmother could’ve read it. Stories she told me and books she gave me have left their traces all over this novel; there are scenes inspired by her childhood, moments shaped by her favorite authors, bits of dialogue I imagine she might say. I would have loved to hear her thoughts on this book. Especially as she got older, she never hesitated to share her opinions, and I imagine she would have told me exactly what worked and what didn’t for her.

What’s the best book you read this year?

Women Talking by Miriam Toews. Reading that book knocked me to the ground. It’s been months and I still haven’t gotten back up.

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

My partner. He’s supported every stage of the development of this novel, from the first days outlining the idea to the year I spent abroad researching it to the many, many rounds of revision to all the publication stress and excitement. Sharing this news with him now was the happiest thing.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

I don’t want to imagine my life without the comedy podcast Hollywood Handbook. Each episode is the highlight of my week. I recommend it to people all the time, and folks inevitably come back indignant and disappointed after they listen. But they just need to try harder to enjoy it!! Please subscribe while keeping its slogan in mind: “Hollywood Handbook: a podcast that only takes 15-20 episodes to get”!!!

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

This answer also relates to a comedy podcast, weirdly enough. Years ago, I listened to the actor Will Ferrell tell a story about art and his father on an episode of WTF with Marc Maron. Ferrell said that when he decided to move to Los Angeles to pursue comedy, his dad, who was a touring musician, said, “If it was all based on talent, I wouldn’t worry about you, because I think there’s really something there. But you have to remember, there’s a lot of luck. And if you get to a certain point—three years, four years, five years—and you feel like it’s too hard, don’t worry about quitting. Don’t feel like you failed. It’s okay to pick up and do something different.”

That advice hit me hard. Since I was a little kid, I’ve dreamed of being an author, someone whose work was on shelves in libraries and bookstores. That vision of the future sometimes energized and inspired me but sometimes poisoned every private pleasure in my life. By the time I was listening to that podcast, ambition had consumed the joys of writing and reading. It overwhelmed me. With every rejection, I felt more sure that my work was bad and that I, too, was bad, because if the work was good and I was good, wouldn’t other people have told me so by that point? Shouldn’t I have gotten the validation I was seeking? I did feel like a failure.

But good ol’ Will Ferrell told me and the rest of that interview’s audience that making a career in the arts depends on luck and opportunity and timing, factors that are out of our control and independent of our work. Your career is not a referendum on your talent or goodness. There’s no reason to beat yourself up. Listening to that, I felt free, for the first time in ages, from self-loathing. His advice let me go back to the page, where writing finally seemed less like a high-stakes audition for becoming one of my childhood heroes and more like the quiet, strange, solitary act of creation it actually was. If I never got my lucky break, if I never became a published author, I would still get to tell myself stories. And there was so much happiness in that.

*

Marlon James, author of Black Leopard, Red Wolf (Riverhead)

What’s the best book you read this year?

Maria McCann’s As Meat Loves Salt. I threw it across the room, yet found myself waking up in the middle of the night, fretting over the characters.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

By never getting it. I don’t believe in writers block. But just in case you do get blocked, read your way out of it.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

Shame, Pride And Prejudice, Sula, Hellboy, Dogeaters, Calvin and Hobbes, Vurt, Summer Lightning and Coin Locker Babies.

You’ve said that you didn’t read the foundational fantasy novels when you were a child. What were the texts that you found most inspiring in your formative years?

X-Men, New Mutants, Teen Titans and Batman.

*

Laila Lalami, author of The Other Americans (Pantheon)

What time of day do you write?

I write in the morning, after having coffee and dropping off my daughter at school. I use internet-blocking software, which keeps me from checking the news or social media. I work for about 5 to 6 hours, then it’s time to catch up on email and other obligations.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

When I’m working on a project, I stick to my routine with the obsession of a maniac. I’ve found that the best way to tackle writer’s block is to avoid it altogether by showing up, every day, and doing the work that’s necessary. When I lose momentum or inspiration, I turn to reading. I think of this is as a necessary refill of my reservoir of words.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Why choose, though? Every piece of culture enriches my life, and my writing, in different ways. I listen to music while I write, watch films and TV every week, and find constant inspiration in the visual arts.

If you have a day job, what is it? How do you negotiate writing and working?

I teach creative writing at the University of California, Riverside. For me, both writing and the teaching of writing are part of the same preoccupation with the narrative arts. I learn about books by teaching them, so while the job does involve many hours away from my own writing, doing it also serves me in different ways. On days when I’m teaching, I have no time to write, but I make up for it by sticking to my routine on other days.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

Never read your reviews. If you believe them when they say nice things about your work, you’re gonna have to be believe them when they don’t. Either way, you’re placing value in other people’s opinions rather than your vision. And in any case, the book is done and you can’t change it. I’ve followed this advice only in the last year, and I have to say it’s been liberating.

*

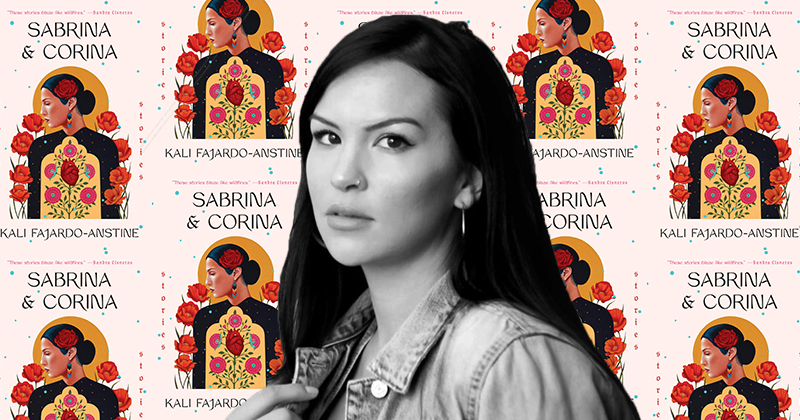

Kali Fajardo-Anstine, author of Sabrina & Corina: Stories (One World / Penguin Random House)

Who do you most wish would read this book?

I imagine there is a girl out there who feels like I did as a child—invisible and often scared, too poor, too loud or too quiet, too strange to be accepted at school, too culturally mixed to be fully considered one thing or another. The person I most want to read this book is that girl. I want her to find home in Sabrina & Corina, a place where she belongs.

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

In a type of euphoric shock, I got off the phone with Lisa Lucas and turned to my father—this man who has supported my love of literature since I was kid—and I got to say, “I am a Finalist for the National Book Award” and he said, “now you’re a big shot. Wanna get lunch?”

What time of day do you write?

When I was younger, I wrote at night because I was often working different jobs during the day. Now, I try to commit full days to writing. I start after breakfast.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I visit historic archives and museums, galleries and art shows, movies and talks. Often these visits are related to my work-in-progress. Other times, these visits remind me of the powers within art making—when I’m inspired, so is my writing.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

Geek Love by Katherine Dunn, Lost in the City by Edward P. Jones, The Rain God by Arturo Islas, Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, Revolutionary Road by Richard Yates, The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro, The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter, Alice Munro’s Selected Stories, Jack Gilbert’s Collected Poems, Ai’s Vice.

Many of the stories in Sabrina & Corina are set in Denver and the fictional Colorado town of Saguarita. Can you tell us a little about your relationship to Colorado and the landscape of the American west?

Denver is the adopted home of my ancestors, the urban area where they first came together in the 1930s. It was the place where they decided to lay down roots, creating a unique convergence to form my ancestry—Picuris Pueblo, Filipino, Mexican, European, Jewish. To me, the American West represents the space where the creation of person like me is possible. But I didn’t see my personal history reflected in the state’s official story and early on I began to wonder why this was.

Previous Article

On the Missing History at New York's Battleship Intrepid MuseumNext Article

Life Inside Guantánamo:An Oral History