Meet the Father of Modern European Fascism: The Marquis de Morès

Sergio Luzzatto on the French Origins of the Revolutionary Far-Right

For nearly half a century, the people of Cannes had called the garden “the Morès Garden”—that is, ever since the marquise, tragic widow of the legendary Marquis de Morès, had holed up in the Château de la Bocca, a stone’s throw from the beach and the sea, as if inside a fort on the Mediterranean coast. The marquise hid there first with her children; then, as the children grew into adults, she secluded alone with the servants, proudly mourning in black like a lady of yesteryear. Rather than close the château’s garden, though, she would leave it open to ordinary people.

After the Great War ended, the marquise passed away, and her children’s visits to Cannes became fewer and fewer. The château and the garden settled into a season of decline, if not abandonment. In the mid-1930s the marquise’s sons put the entire property up for sale, but there were no buyers. Then, on April 21, 1942—in the midst of a new world war—Cannes mayor Antoine Blanchardon, a notary public by trade, seized control of the matter. At a judicial auction announced by the court in Grasse, the municipality of Cannes exercised its right of first refusal and acquired the property. And now, on Monday, July 27, the mayor was there at city hall, in front of the four members of the city council, to sign a resolution he cared deeply about: the official naming of the garden after the Marquis de Morès.

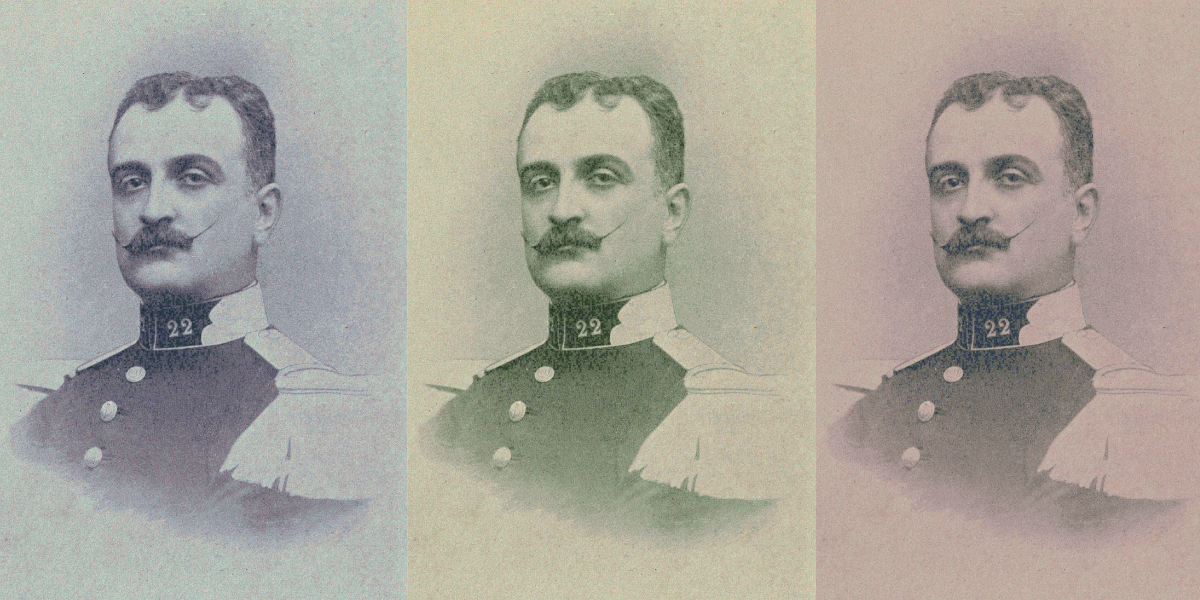

Ascribing the name Morès to the garden was not just a matter of access to the space with a seal of formality—and about honoring the widow’s formidable husband. In Vichy France, no one deserved the “gratitude of the people,” according to the text of the resolution, more than the Marquis de Morès. From 1858 to 1896, Morès’s short existence, which had unfolded throughout the four corners of the world, had stood as definitive proof of his belonging to the “race of leaders and warriors, of those who make their way by paying with their person.” In the resolution sponsored by the mayor of Cannes, the marquis was described in the present tense, as if he were a force still in action: “Heedless of danger, Morès fights with equal determination against cowboys in America, tigers in India, bands of looters on the Chinese frontier, Jews and British agents in France.” “A socialist at heart,” and the proprietor of his famous “popular butcher shops” in America, Morès had also been “one of the active leaders of the antisemitic party.” And for this he was assassinated, at the age of thirty-eight, in Africa in 1896. It was “they,” the Jews, who had “ordered him murdered.”

Already in fin de siècle France, men like the Marquis de Morès had pursued the goal—the inherently fascist goal—of carrying out a revolution that was political, intellectual, and moral, but not social or economic.

On July 27, 1942, Blanchardon had no trouble persuading the delegates of the municipal council of Cannes to sign the resolution. All five had been appointed by France’s head of state, Marshal Philippe Pétain, and considered themselves his loyal followers. In the second half of the 1930s, when France was still the Third Republic, the notary Blanchardon had made his political debut as a local leader of Jacques Doriot’s French Popular Party: a party of fascist collaborationists avant la lettre.

When France fell after the Wehrmacht’s blitzkrieg in June 1940, both the future mayor and the future city council members had belonged to the Cannes branch of the French Legion of Fighters, the war veterans who thought of themselves as the marshal’s praetorians within the “free zone” (the half of France that Third Reich soldiers had given up directly occupying). After all, Marshal Pétain himself surely would have signed the Morès Garden resolution—not only because of his privileged relationship with the Côte d’Azur, where he had a home a few kilometers from Cannes, or because of the Legion’s political performance of collaborationism in the Alpes-Maritimes department, but because of the personal memory that Pétain would have had of the marquis. In 1876, both Pétain and Morès—one twenty years old, the other eighteen—had passed the entrance exam for the École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr, the army academy. For the next two years, they would train together in the art of war, to the greater glory of France in the world.

The text of the resolution did not neglect to mention this. It also mentioned that the marquis and the marshal had belonged to the same École de Saint-Cyr class as “Father de Foucauld,” the Viscount Charles de Foucauld. Foucauld had later left the army to become a Trappist monk and had established himself as a missionary in Tamanrasset, Algeria, in the middle of the Sahara Desert; he was killed there by local thugs in 1916. One could hardly have imagined a more dramatic and instructive coincidence: Morès and Foucauld, two aristocratic friends in the same class at Saint-Cyr, both martyred in the Sahara, twenty years apart, as they sought—each in his own way—to improve the fortunes of France and humanity. As the resolution continued, it described how, in Africa, the marquis was “disgusted with politics for all that it entails that is tortuous and low, [but he was] attracted by a struggle that he considers clearer and nobler…to target the Anglo-Saxon and Jewish hoarding, the coalition that runs the whole game of world politics, and which he has been able to unmask.”

In July 1942, the mayor and city council of Cannes could only have had in mind the ongoing world war: the North African campaign pitting the Allies against the Axis powers, and the rumors that were circulating about an imminent Anglo-American landing along the coast of Algeria. Almost fifty years ahead of the battles of World War II, the Marquis de Morès had faced death in order to avoid handing Africa over to the British and the Jews.

The “Jews’ hatred” had been the force driving the Bedouins or Berbers who had killed Morès in a Saharan oasis. As for the French government, after obstructing the marquis’s mission to Africa in every way, it had not bothered to notify the marquise of her husband’s death: The poor woman had “learned the news on the street, from the newsboys.” There followed a dutifully “grandiose” funeral for Morès at Notre-Dame Cathedral. But with that concluded, the government of the Republic had left the widow to fight alone a battle to locate Morès’s killers in the Sahara and bring them to justice: “Madame de Morès does not give up the fight, and there is a tragic greatness in the example of this beautiful young woman who, in spite of the French government, in spite of the hatred of the Jews and the Anglo-Saxons, succeeds in having her husband’s murderers imprisoned and put to death.”

At the end of 1896, the marquise had Morès’s remains moved from the Montmartre cemetery in Paris to the Grand Jas cemetery in Cannes. Now, forty-six years later, it seemed the patriotic duty of the municipality of Cannes to name the gardens of the Château de la Bocca after Morès. In anticipation of a further tribute owed to the marquis by France and by history, the resolution announced, “It is here, in this park where Morès was happy and to which Cannes gives his name today, that one day, no doubt soon, a monument of gratitude and reparation will be erected to one of France’s bravest and most farsighted sons.”

*

Farsighted, indeed, was the Marquis de Morès. The pioneer of the war against the Jewish race that could finally be said to have reached its peak in the France of 1942 and Europe more widely. On that Monday, July 27, while at Cannes city hall Mayor Blanchardon and the four Vichy council members signed their names at the bottom of resolution No. 58, 900 kilometers farther north—at the Épernay train station in the Marne, in the “occupied zone”—a twenty-nine-year-old woman managed to throw a letter from the sealed carriage of the train designated by the Germans as transport D 901-6, en route to the Auschwitz extermination camp in Poland. A merciful hand picked up the letter and mailed it to Paris. The addressee was the caretaker of the building at No. 2, Passage Maslier, 19th Arrondissement, in the Buttes-Chaumont district. “I don’t know if this letter will reach you,” it read.

We are in a cattle car. We have been deprived of even the most essential toiletries. For a three-day journey we barely have bread, and water by the drop. We take care of our needs as best we can, on the ground, women and men. There is a dead woman among us. When she was dying, I called for help. Perhaps she could have been saved. But the cars are sealed, she was left without help. And now we have to endure the smell of death. We are threatened with beatings and gunfire. My sister and I encourage each other, we don’t give up hope. I hug you all, the children, family and friends. Sarah.

The letter’s author, Sura Feldman Goldfajn, was being returned by cattle car to her native Poland. Like her sister, Cypra Feldman Ajzenberg, she would not be among the thirteen survivors out of the thousand coerced passengers on convoy D 901-6.

The deportation of Jews to Auschwitz had begun in France in March but did not become methodical until early June, a month after Louis Darquier de Pellepoix was appointed to head the Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives, the administrative arm of the Vichy regime committed to the destruction of the Jews of Europe. In the first phase, deportations had taken place only in the occupied zone. Within a month and a half of his arrival at the top of the Commissariat Général, Darquier could boast of having helped organize the departure to Auschwitz of ten train convoys with a thousand people on each, as well as preparing for the gigantic Parisian raid of July 16-17 that would go down in French history as the Vélodrome d’Hiver roundup, with 13,000 Jews arrested within twenty-four hours, a third of them children, all destined for the death camps. And it would be in that raid, among the 13,000, that sisters Sura and Cypra Feldman were captured.

For a long time nothing more than a loser, an obscure journalist, and a failed entrepreneur before becoming a professional antisemite, Darquier de Pellepoix collaborated with the Nazis more effectively than any other French fascist in the effort to bring about the “Final Solution” to the “Jewish problem.” And he did so in the belief that he was following—as one follows the North Star—the path established by the Marquis de Morès. On May 11, 1942, Darquier gave the most widely circulated of France’s newspapers, Paris-Soir, his first interview as commissar general. “The Jewish problem is not a recent or passing problem. Nor is it a specifically German problem. Let me just say that at the beginning of this century it was France that led the anti-Jewish struggle with three men of great class: the doctrinaire Gobineau, the polemicist Drumont, and that great lord of action who was the Marquis de Morès.”

A man of little education, Darquier managed to get two facts wrong in a single sentence. Édouard Drumont, the founder in 1892 of the antisemitic newspaper La Libre Parole, lived until 1917, but Arthur de Gobineau, the author of Essay on the Inequality of Human Races, had passed away in 1882, and Morès had died in 1896—hardly heroes from “the beginning of this century.” Nevertheless, the new commissar general was correct when, on his first public outing as chief executive of the Final Solution in France, he claimed that his own country had been the first to see antisemitism transfigured from a religious or cultural animosity to a political program. And he was equally correct in distinguishing between those three gentlemen “of great class”: the two men of the pen, Gobineau and Drumont, and the man of action, Morès.

With a commissar general for Jewish affairs as motivated and efficient as Darquier de Pellepoix, SS Captain Theodor Dannecker—Adolf Eichmann’s trusted man in Paris—was quick to plan an extension of the roundups to the so-called free zone. He visited Nice, the capital of the Alpes-Maritimes department, between July 12 and 14, a fortnight before the mayor of Cannes resolved to name the gardens of the Château de la Bocca after the Marquis de Morès. There was a need to “inspect Jewish material,” Dannecker told the Vichy police chief. Later, after returning to Paris, Dannecker explained to the prefect of the Alpes-Maritimes that it was necessary to set up a reception place for the “individuals in question.” Dannecker communicated this via coded telegram, as the plan was to deport to Poland a total of 10,000 foreign Jews (that is, Jews not born in France) from the free zone, with the first group numbering 1,800, and he wished to avert the risk of a leak that might allow any of them to escape. The month of July 1942 was the turning point in the French implementation of the Final Solution.

The Jews (including children) who were captured in the South of France in the roundup that took place on August 26 and 27, 1942, numbered 6,584.26 Of these, 510 were arrested in the Alpes-Maritimes, with 62 of those in Cannes. The French police and gendarmes were only relatively satisfied with these results: In the Alpes-Maritimes, two out of three Jews on file had escaped capture (for now). In the case of Cannes, the municipal secretary—who clandestinely worked with a Catholic network to assist persecuted Jews—would recount after France was liberated how he and other city hall employees had fabricated documents for the city’s Jews, while keeping Mayor Blanchardon in the dark. Blanchardon was a local leader in Doriot’s French Popular Party, so “of course we did not trust him,” the municipal secretary would recall. With good reason: Blanchardon had relieved the Cannes police chief of his duties in December 1940, as the chief was known to be a sympathizer of the Popular Front, and thus of the Jewish former prime minister Léon Blum, and for this reason he did not seem prepared to take part with sufficient zeal in what the mayor, following the example of Marshal Pétain, characterized as the “noble task” of the “redressement of France.”

*

Also dated July 1942 is an essay written in New York by a German Jew who had escaped from Hitler’s Germany in 1933 and then from Vichy France in 1941: Hannah Arendt. “From the Dreyfus Affair to France Today” is the title of that essay, the first that Arendt published in the United States. “Dreyfus und die Folgen”—that is, “Dreyfus and the Consequences”—was the (perhaps more appropriate) title on the original German-language typescript. For this was what Arendt’s debut on the American intellectual scene was about: assessing the consequences for the present time of the Dreyfus affair, which around the turn of the century had shaken France to its foundations.

For a dozen years beginning in 1894, the Jewish army captain Alfred Dreyfus, unjustly accused of treason by the French army’s top brass, stripped of his rank, and deported to Guyana, had been the human stake in an all-out struggle between those who defended his innocence, the dreyfusards, and those who wanted him found guilty at all costs, the antidreyfusards. For Arendt, the essay was an attempt to understand how and in what sense that half-century-old history could help explain—far beyond its chronological and geographical boundaries—the ongoing tragedy of the destruction of Europe’s Jews, pursued by the Nazis and their auxiliaries in Hitler’s empire. Could that history, she wondered, indicate a point of origin from which the present wickedness had grown? Could it reveal the birth of fascism?

Hannah Arendt included a fleeting reference in the essay to the Marquis de Morès, “organizer of the butchers of Paris.” But Arendt’s knowledge of the Dreyfus affair was limited, as was her general knowledge of the history of antisemitism in France. Dreyfus and Morès were of interest to Arendt insofar as they promised (as she explained to students at Brooklyn College in a course she taught in the summer of 1942) to “guide us in understanding the real nature of Fascism.” In her view, fascism was “invented some fifty years ago and never has been modernized. It is Fascism all the same.” According to Arendt, the Dreyfus affair had left the Third Republic a double legacy that had to be taken into account in order to put Vichy France in perspective: on the one hand, hatred for Jews; on the other, distrust of everything republican, parliamentary, and governmental.

Morès thus was the first to try to handle the peculiar mixture of racial hatred, alleged interclass solidarity, and organized paramilitary violence to which Benito Mussolini would give the name fascism.

The essay, included in Arendt’s epoch-making 1951 book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, would profoundly influence some of the most authoritative scholars of modern France. One of them is the Israeli historian Zeev Sternhell, who in 1978 rocked the international academic scene with a book whose subtitle counted as much as the title: The Revolutionary Right: The French Origins of Fascism. In Sternhell’s view, it was in late nineteenth-century France that a generalized revolt against the principles of 1789, the rights of man, and liberal democracy as a whole had taken hold. As a “system of thought,” fascism had been a “French product.” It had not needed to wait for Benito Mussolini to become influential in Italy during the First World War.

Already in fin de siècle France, men like the Marquis de Morès had pursued the goal—the inherently fascist goal—of carrying out a revolution that was political, intellectual, and moral, but not social or economic; of preserving free trade and the market economy, but rejecting liberalism and the values of democracy. This had been, according to Sternhell, the historical role of the revolutionary right. And this had been a lesson that Mussolini learned well, abetted by his readings and acquaintances as a young exile in French Savoy during the early twentieth century.

Sternhell’s thesis on the French origins of fascism was fiercely contested in a France that, even as late as the 1980s, was still grappling with the historical entanglement between the political cultures of the Third Republic and those of the Vichy state. His argument faced intense opposition from a nation reluctant to acknowledge fascism as an integral part of its own history. In particular, France was struggling to confront how the cultural roots of collaboration with Nazi Germany during the “terrible years” of the occupation were embedded in the democratic and independent republic of the Dreyfus-affair era. After all, the Fifth Republic was being led at the time by François Mitterrand, whose right-wing activity as a youth remained unknown to the general public until the following decade. Beginning in 1934, Mitterrand had actively participated in extreme right-wing political movements, and even in 1942—before joining the Resistance—the future socialist leader had served Marshal Pétain, both as a member of the French Legion of Fighters and as a ministerial official in Vichy.

All this is not to say, however, that Sternhell’s thesis on the French origins of fascism should be taken for granted. As early as the 1980s, critics effectively challenged his interpretation, arguing that he presented fascism as an essentialist genealogy—one based almost entirely on ideas, detached from the existence of a fascist party or regime. Even today, if we agree to accept—for the sake of discussion—the applicability of the category of fascism to late nineteenth-century France, the historical forms of such a fluid ideology must be studied less through theories than through practices. From its inception, fascism has functioned less as a system of thought than as a system of action.

*

The Marquis de Morès was the first leader in the West to emerge on the political stage as a populist, an antisemite, and (though the word did not yet exist) a fascist militiaman, all at once. His rise to prominence in France was fueled not only by incendiary rhetoric but also by the tactical and strategic use of intimidation, provocation, and violence, culminating in the role Morès played as the dark soul of the Dreyfus affair. And when, in 1893, the story of the charismatic marquis became that of his precipitous downfall, then the legend began, leading up to the Nazi-fascist rediscovery of Morès in Vichy France. His brief and adventurous existence triggered ideological and practical dynamics that would dominate the twentieth century, in and beyond the age of fascisms.

In the varied circumstances of life, Morès found new confirmations of a theory he had gathered as a boy from his Jesuit teachers: that the capitalist elites not only of France but also of the whole world were now contaminated by Jewish poison, and that the historically ordained mission of an authentic gentleman consisted in fighting Jews as well as any other socially and politically divisive minority, in the name of a newfound interclass cohesion. A man of action, Morès was also (in his own, hardly intellectual way) a man of thought. Wherever on the planet he found himself, he was always moved by the intention (or obsession) to reaffirm, in the new world of universal male suffrage, mass society, and imperialistic competition, the ancient primacy of white Christians, a primacy that he had been brought up to believe was a birthright. The marquis wanted to reaffirm that primacy with updated tools, newer and more effective than those of the old-blood aristocracy and early colonialism, though with a kind of chivalrous attention to social duties that—even after the end of the old regime—still persisted among men of rank.

Backed by his charming American wife, Medora von Hoffmann, the former cavalry officer made his life a picaresque ride across four continents. In the 1880s he was a cattle rancher in the Dakotas, where he sought to revolutionize the nascent meat industry. In the Great Plains of the American West, where he breathed in the air of an acerbic and tentative antiestablishment movement—the same one that would shortly thereafter promote in the United States the birth of the People’s Party (often known as the Populist Party)—Morès opposed, though in vain, the cartel of big businessmen, some of them Jews, who controlled the meat trade between Chicago and New York.

After failing as an entrepreneur in America, and after an interlude in Asia in an attempt (also failed) to build a railroad on the Vietnam-China border, Morès returned to France to pursue a political career as a populist leader and an antisemitic demagogue. At the height of his trajectory, the marquis could delude himself into thinking that he controlled, in the streets of Paris, a mass army of disoriented, impoverished, angry workers. And he could delude himself that he would soon be hailed by the whole of France as a savior of the homeland.

Morès thus was the first to try to handle the peculiar mixture of racial hatred, alleged interclass solidarity, and organized paramilitary violence to which Benito Mussolini would give the name fascism. In fact, from 1915 onward, historical fascism would require a variety of structural conditions in order to take shape in Mussolini’s Italy and then spread from Italy to the rest of Europe. Neither a “movement fascism” nor a “regime fascism” ever could have existed without what was triggered by World War I and the Russian Revolution: the exacerbated militarism of the elite corps, the “plutocratic” imperialism of British colonialism, the materialism of the new American superpower, the perceived planetary threat of “Judeo-Bolshevism.” The historian must always beware of confusing filiation with explanation. However, this book aims to show how the Marquis de Morès, without having been the architect of fascism, was one of its fathers.

Of course, once we start moving backward in time and far in space in search of the precursors of fascism, it is not only late nineteenth-century France that should be taken into account. Signs of a generalized revolt against the liberal establishment were visible in Central Europe as much as in Western Europe, and especially in an increasingly unhappy felix Austria—more and more threatened, in the era of the Depression, by the anger the petty bourgeoisie and working classes felt toward the system.

The primogeniture of fascism could legitimately be attributed as much to a Parisian gentleman such as the Marquis de Morès as to a Viennese gentleman such as the knight Georg Ritter von Schönerer, himself a populist leader and antisemitic demagogue who was a curious mixture of aristocratic pride, bourgeois philistinism, and plebeian gangsterism. It is no coincidence that historians have identified fin de siècle Vienna as the birthplace of a new “postrational politics,” which they described as a collage of fragments of modernity, glimpses of futurity, and resurrected shreds of a half-forgotten past; in this way, they have spoken of a “protofascist politics.” Nor is it a coincidence that the figure of von Schönerer would inspire an unhappy and rebellious provincial teenager named Adolf Hitler. Thus, in Vienna and beyond, the new postrational politics proved to be built on its own rationality. In fin de siècle Paris, Morès felt compelled to provide a strong response to what men like him—the men of the revolutionary right—considered a real crisis of civilization, precipitated by the combined effects of incipient globalization and a looming proletarian insurrection.

On the economic terrain, a third way had to be found between liberalism and socialism that would guarantee (or impose) a new harmony between capital and labor; on the cultural terrain, the aim was to reinforce a hierarchical order that would save the West from the Jewish conspiracy and the white race from the revolt of the inferior races. Starting from France, it was necessary—as Morès theorized in 1894—to rebuild the virtuous bond intended to keep the different components of human society united; in the Western republican tradition, this bond had since ancient times been symbolized by the fasces, a bundle of rods. Therefore, though privileged both by birth and by upbringing, the Marquis de Morès wanted to build his political fortunes on an alliance among the less fortunate sectors of the people of Paris: butchers, coachmen, and small traders destabilized by the advent of new production and distribution systems, worried about the impact of new technologies, threatened by the increasingly rapid developments of financial capitalism.

While chronologically Morès’s life belongs in its entirety to the nineteenth century, ideologically and culturally it anticipates so much of the twentieth century.

But Morès deserves to be recognized as a father of fascism not merely for having applied the old metaphor of the fasces to a new hierarchical order, characterizing it as an interclass panacea. He also stands out for having been among the first European political leaders—or perhaps the very first—to sense that the modern world was opening up to new forms of the relationship between social order and social control, even to the point of calling into question the very principle, sacrosanct for centuries in Europe, of the state’s monopoly on the exercise of legitimate violence. In this regard, his experience in the American West of the 1880s proved decisive: There, the flourishing of vigilantes, private detectives, and armed guards—serving the protection and profit of agrarians and industrialists—gave rise to unprecedented forms of coexistence between public and private violence. A staunch advocate of vigilantism on the semideserted prairies of the Dakotas, the Marquis de Morès thus prepared to arm himself even in France, bringing something like his own personal militia into the most crowded and elegant streets of the capital.

In the Paris of the early 1890s, Morès’s praetorian guard was mainly composed of butchers and butchers’ apprentices, who gained notoriety in the press for the blue blouses (long, loose overgarments) that were more or less stained red with animal blood from their work and which they also wore in their fights. It was as if they anticipated a chromatic variation on the theme of Mussolini’s Blackshirts or Hitler’s Brownshirts.

*

Forgotten today, the figure of the marquis was well known to his contemporaries. In the last decade of the nineteenth century, Morès came to be a worldwide celebrity. This was possible thanks to an ability all his own to play the role of leader in a performative way. Shocking statements to the press, carefully choreographed and provocatively managed street demonstrations, duels that were as sensational as possible (and sometimes deadly): Morès was a forerunner of political modernity partly because he always had an audience in mind. Every speech he made assumed a calculation, and involved an investment in audience response; every action he took was undertaken to elicit a reaction. At the dawn of the mass media age, Morès already interpreted politics as an art of communication.

Nowhere did he demonstrate his performative streak as cynically and as effectively as in his actions as an antisemitic agitator. And not just any agitator: a protagonist in the historical evolution of traditional antisemitism into political antisemitism. The marquis worked tirelessly to construct in public opinion the figure of the Jew as a scapegoat for the failures of modernity. In particular, as an accomplished swordsman, Morès achieved a thunderous crescendo around the social profile of the Jews he challenged to duels.

At first he took on a journalist who was also a member of France’s Chamber of Deputies, then a civil servant strongly disliked by the working class, and finally an army officer who was not Captain Alfred Dreyfus himself but just as innocent and—it may well be said—even more unfortunate, inasmuch as the marquis, in order to stage political antisemitism, did not hesitate to get his hands bloody. In general, Morès systematically took care to create a public scandal in which Jews were positioned as corrupters of morals or, even worse, poisoners of wells: the first and last culprits of the threat of ruin looming over the Christian West, just when white Christians seemed masters of the planet.

Morès was a serial failure. Across four continents, his visionary quests as an entrepreneur, explorer, chieftain, and adventurer were all united by his lack of success. But dying a loser is often the fate of pioneers. Moreover, Morès fell in battle in the Sahara when he was thirty-eight years old—an age when neither the first overtly successful fascist, Mussolini, nor the most resoundingly successful of his imitators, Hitler, had yet tasted the intoxication of victory; on the contrary, both had repeatedly drunk from the bitter chalice of failure, marginality, and humiliation. In Europe between the two world wars, an interweaving of momentous circumstances secured for those two men who had come from below, the son of an Italian blacksmith and the son of an Austrian customs officer, respectively, the glory precluded for a French man of the previous generation who had instead come from above—the son of a duke. Regardless of these fundamental differences, the story of the Marquis de Morès should be read today as an all too instructive parable.

Hierarchical order, identity politics, conspiracy theories, prejudice against those who are different, incitement to racial hatred, body language: While chronologically Morès’s life belongs in its entirety to the nineteenth century, ideologically and culturally it anticipates so much of the twentieth century, and even—unfortunately for us—more than a few developments of the twenty-first century.

__________________________________

From The First Fascist: The Sensational Life and Dark Legacy of the Marquis de Morès by Sergio Luzzatto. Copyright © 2026. Available from Harvard University Press.

Sergio Luzzatto

Sergio Luzzatto is Emiliana Pasca Noether Chair in Modern Italian History at the University of Connecticut. A winner of the Cundill History Prize, he is the author of The Body of Il Duce and Primo Levi’s Resistance, among other books.