Meet the Beloved Pet Ravens of Charles Dickens

Grip I, Grip II, and, You Guessed It, Grip III

Lots of writers have kept corvids as pets and companions. Lord Byron kept a tame crow, I believe, though in fairness he also kept dogs, monkeys, peacocks, hens, an eagle, and a bear. The poet John Clare kept a raven, as did the American writer Truman Capote, whose raven was called Lola. Capote wrote about Lola in some detail in an essay first published in 1965, claiming that she used to cache various items in his bookcase behind The Complete Jane Austen, including a “purloined denture [. . .] the long-lost keys to my car [. . .] a mass of paper money [. . .] old letters, my best cuff links, rubber bands, yards of string” and “the first page of a short story I’d stopped writing because I couldn’t find the first page.” This all sounds rather unlikely to me, since the ravens in the Tower of London mostly tend to cache mice and bits of rat, but Mr. Capote was clearly a highly literary man with a highly literary raven. Either that, or he was making it up.

But it was of course the London writer, Charles Dickens, who kept the most famous ravens of all. Dickens mentions the Tower quite a few times in his novels. The Quilps in The Old Curiosity Shop live on Tower Hill. David Copperfield brings Peggotty to the Tower for a tour. And in Great Expectations Pip and Herbert row Magwitch past the Tower on their ill fated trip down the Thames. I’ll confess that this is where my wider knowledge of the work of Dickens ends-though when it comes to ravens, I can categorically state that he knew his birds.

The story of Dickens’s ravens is well-known. In January 1841, the great man wrote to a friend about the new novel that he was working on. His big idea, Dickens wrote, was to have his main character “always in company with a pet raven, who is immeasurably more knowing than himself. To this end I have been studying my bird, and think I could make a very queer character of him.” And a very queer character he makes of him indeed in Barnaby Rudge, his fifth novel, which is set during the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots of 1780, and in which the eponymous hero has a raven named Grip who accompanies him everywhere he goes. (Here at the Tower, our Gripps have always had an extra “p” for reasons not entirely clear, though I suspect a clerical error.)

I may have a rather partial view, but to my mind Dickens counts as a genius not because of his prolific output, nor because of his famous public performances and his great public works, but because he gets every detail about ravens correct! He describes Grip’s voice as being “so hoarse and distant, that it seemed to come through his thick feathers rather than out of his mouth,” which is exactly where a ra ven’s voice seems to come from. And the way he describes Grip’s walk-well, that’s the way our Gripp walks today!

How did Dickens get it so right when so many other writers seem to get it so wrong, or simply see the ravens as symbols? He lived with the birds, that’s how. He observed them. He spent time with them. As he explained in the preface to Barnaby Rudge, “The raven in this story is a compound of two great originals, of whom I was, at different times, the proud possessor.” Scholars believe that during his lifetime Dickens in fact kept three or four ravens, the first of whom, Grip, liked to nip the ankles of Dickens’s children, whereupon he was barred from the house and banished outside. Unfortunately, just a few weeks after Dickens wrote about his idea of put ting a raven in a novel, Grip died, as a result of having drunk or eaten some lead paint.

“To my mind Dickens counts as a genius not because of his prolific output, nor because of his famous public performances and his great public works, but because he gets every detail about ravens correct!”

Dickens replaced Grip with two new birds: a second raven, also called Grip, and an eagle. The second Grip, according to Dickens’s eldest daughter, Mamie, was “mischievous and impudent” and was eventually succeeded by a third Grip, who was so dominating that the family’s large mastiff, Turk, even allowed him to eat from his bowl.

A true measure of Dickens’s affection for the first Grip is that he had him stuffed and mounted in a case which he kept above his desk. (Actually, Dickens made a bit of a habit of stuffing his dead pets. When his cat Bob died, for example, he had one of his paws made into a letter opener.) After Dickens’s death in 1870, a sale was held of his effects and the stuffed Grip eventually made it to America, where he can be seen in the Free Library in Philadelphia. A trip to see Grip in Philadelphia is another one of those adventures I’ve promised myself one day, though we do in fact have a perfectly good stuffed raven of our own here at the Tower. We have a little private museum on the ground floor of the Queen’s House, which is not open to the public, but in there you’ll find a rather handsome stuffed raven standing to attention on a perch in a very fine carved wooden case.

A plaque on the case reads, “Black Jack, whose death was occasioned by the fearful sound of cannon upon the funeral of H. G. (His Grace) the Duke of Wellington, late Constable of the Tower of London, anno 1852.” Some people have suggested that Black Jack may himself have been one of Dickens’s birds, but I have seen no conclusive proof. What I do know is that several of the Tower ravens have been named in honor of Dickens’s raven, as is our current Gripp, and that one of Gripp’s earlier namesakes was resident during World War Two, he and his mate Mabel and another raven named Pauline being the only ravens to survive the Luftwaffe’s bombing of the Tower, though alas, the Tower records suggest that after surviving the war, Pauline was killed by Mabel and Gripp. A truly tragic Tower tale.

Of course , the influence of Dickens’s Grip goes way beyond the naming of our birds. Dickens was a great celebrity, and a bit like celebrities today with their sharpeis and French bulldogs, he helped set a trend. Thanks to Dickens and Grip, ravens became fashionable—maybe that’s where the Yeoman Warders got the idea of importing a few tame ravens into the Tower in the 1880s? I offer this idea as a fruitful area of research to any corvidologists and Dickensians out there.

__________________________________

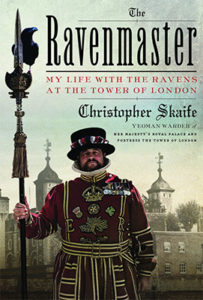

From The Ravenmaster: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London. Used with permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2018 by Christopher Skaife.

Christopher Skaife

Christopher Skaife is Yeoman Warder (Beefeater) and Ravenmaster at the Tower of London. He has served in the British Army for 24 years, during which time he became a machine-gun specialist as well as an expert in survival and interrogation resistance. He has been featured on the History Channel, PBS, the BBC, Buzzfeed, Slate, and more. He lives at the Tower with his wife and, of course, the ravens. The Ravenmaster is his first book.