Meet the Baillie Gifford Nonfiction Prize “Winner of Winners” Shortlist

The Best in Nonfiction

In honor of its 25th anniversary, the Baillie Gifford Nonfiction Prize will announce on Thursday its “Winner of Winners” award, which singles out the best of its annual prize-winners over the last quarter century. The shortlist includes some of the most important nonfiction writers working today: Patrick Radden Keefe, Wade Davis, Barbara Demick, Margaret MacMillan, James Shapiro, and Craig Brown. Read on below to find out more about their groundbreaking work.

*

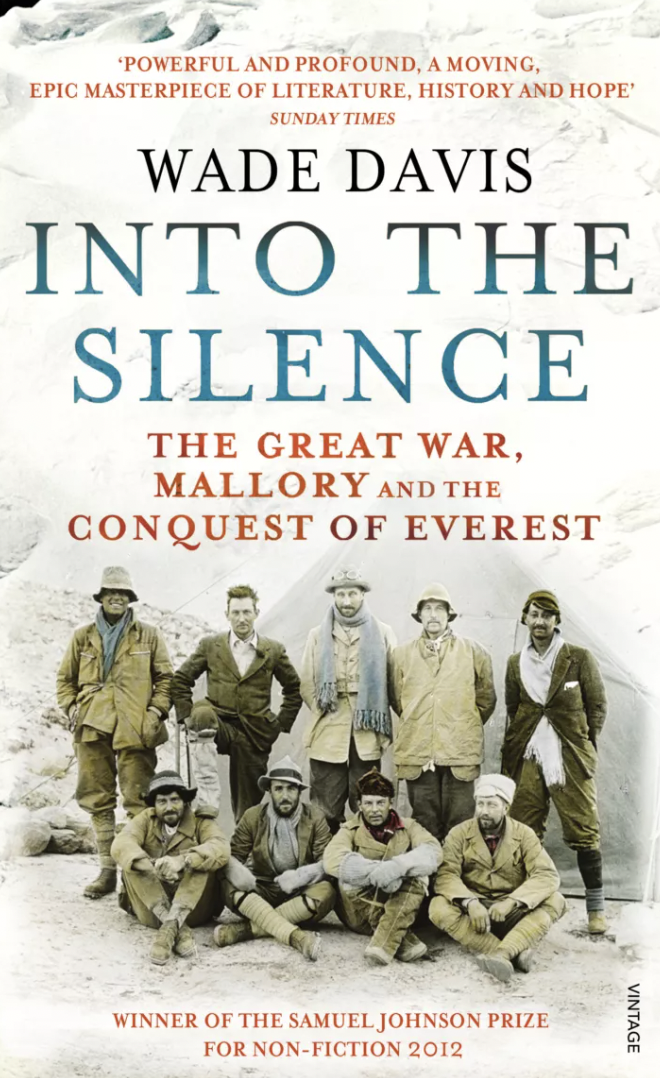

Wade Davis (Canada)

Winner of the 2012 Samuel Johnson Prize (the precursor to the Baillie Gifford Prize) for Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory and the Conquest of Everest

Into the Silence tells the story of the British Everest expeditions of 1921-24, against the backdrop of Tibet and the Raj, and in the wake of a war that had changed everything. If the quest for Everest began as a grand imperial gesture, as redemption for an empire of explorers that had lost the race to the Poles, it ended as a mission of regeneration for a country and a people bled white by the Great War. Of the 26 British climbers who walked 400 miles off the map to find and assault the highest mountain on Earth, twenty had seen the worst of the fighting. Six had been severely wounded. Two lost brothers. All had endured the slaughter.

In 1924 Mallory and Irvine were last seen going strong for the top as the mist rolled in and enveloped their memory in myth. But what interested me from the start was not whether Mallory reached the summit, but rather why on that fateful day he kept going. An answer came in a single phrase uttered by one of the survivors as they retreated from the mountain: “The price of life is death.” Mallory walked on because for him, as for all of his generation, life mattered less than the moments of being alive.

To pursue this theme, I had to show, not tell, what the war had implied. Over twelve years I found out where each man had been every day of the four years and four months of the war. What each had endured was ascertained from regimental diaries, letters, and journals. Archival research led to 57 institutions in several countries; my research library grew by more than 600 books. On foot over several months I retraced all the Tibetan approaches to the mountain, climbing to heights in a deliberate attempt to experience the severe effects of oxygen deprivation.

To understand the Tibetan side of the story, I lived for weeks in a Buddhist monastery as a guest of Trulshik Rinpoche, spiritual heir to Dzatrul Rinpoche, the lama of Rongbuk encountered by the British in 1922. With the help of monks in Kathmandu, I had Dzatrul Rinpoche’s namthar, or spiritual autobiography, translated for the first time. A deep immersion in Buddhist texts left little doubt that, while Everest was never a sacred mountain, the entire time the British were within its shadow, they were walking in mystic space.

–Wade Davis

Wade Davis Recommends:

Vera Brittain, Testament of Youth

Vera Brittain, a nurse, lost her fiancée, Roland, her two best friends from Oxford, and finally her beloved brother Edward. By the end of the war, she wrote, there was no one left to dance with. The war, wrote Roland in a letter to Vera, “distilled all youth and joy and life into a fetid heap of hideous putrescence.” Testament of Youth traces a journey from innocence through horror, agony to revelation. It is to my mind the most poignant and heartrending memoire to emerge from the Great War.

T.E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom

T.E. Lawrence famously lost the original 250,000-word manuscript of his account of the Arab Revolt at Reading Station while changing trains at Christmas 1919. In a fever pitch he rewrote the entire book from memory. Deeply conflicted by his public image as the hero of a war that had crushed the very notion of heroism, he began the first chapter: “Some of the evil of my tale may have been inherent in our circumstances.” He went on to describe how his men lay naked shamelessly beneath the innumerable silences of stars. If he were to be a war hero, British society would have to deal with the truth of his desires and compulsions.

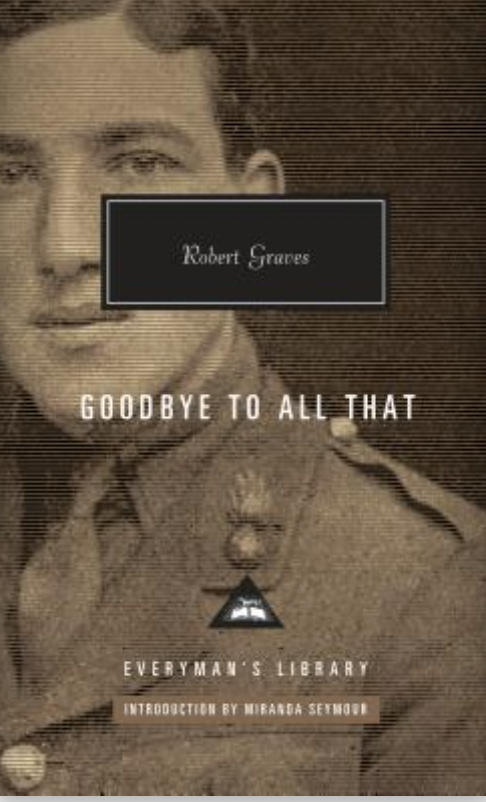

Robert Graves, Goodbye to All That

At the Somme in 1916 Graves, severely wounded by shrapnel that blasted a hole through his chest, was left among the dead. The next morning a burial party found him alive, and for four days he lay delirious beneath the searing sun, just one of tens of thousands of wounded awaiting evacuation. He was just 21. He had been Mallory’s student at Charterhouse, and Mallory later stood as best man at Graves’ wedding in January 1918. Wilfred Owen was among the guests. The night the war ended, Graves went out alone, as he recalled in this stirring memoir, and walked “along the dyke above the marshes of Rhuulan, cursing and sobbing and thinking of the dead.”

Sebastian Faulk, Birdsong

The regular British army required 2,500 shovels. In the mud of Flanders ten million would be needed. Throughout the war 25,000 Welsh coal miners lived underground, tunneling beneath enemy lines to lay charges of TNT, explosions that were heard as far away as southern England. The Germans naturally were doing the same to the Allied front lines. The climatic scene of Birdsong, in which soldiers of both sides engage in hand to hand combat in the darkness far beneath the earth, is the most harrowing I have ever read in the vast literature on the war.

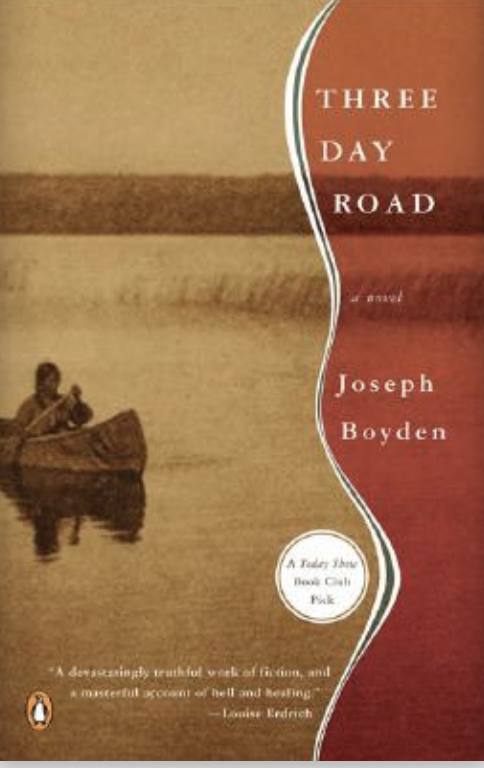

Joseph Boyden, Three Day Road

On April 22, 1915, when Germans attacked using poison gas for the first time, it was only the suicidal stand of the Canadians that prevented a complete rupture of the British front. The reputation of the Canadian forces only grew as the war went on. Germans came to know that if they faced Canadian units, an Allied attack was imminent. Three Day Road follows the lives of two Cree men, friends since childhood, raised as hunters in the forests of Manitoba, and recruited as snipers in the Canadian army. Though spare in style it reads as one long haunted hallucination as the horror of their experience echoes with memories of their youth. The Western Front as seen through the lens of the shaman.

Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory

If the war shattered the last vestiges of the old order, making a mockery of notions of glory, honour and valour, peace heralded the birth of modern times, a new century stained, as Winston Churchill would write, in blood. Caught between worlds, the old and the new, spinning in a whirlwind of psychological and social uncertainty, was an entire Lost Generation. “By the end of 1916,” Nancy Cooper famously remarked, “every boy I had ever danced with was dead”. Stephen Spender wrote that in the wake of the war the British middle class continued to dance, unaware that the dance floor beneath their lives no longer existed. Without doubt this is the seminal book for understanding what the war ultimately implied for Britain and indeed the world

*

The Crowning of Everest, five-part radio series written and presented by Wade Davis for BBC4 and BBC Sounds, Manchester and London, air dates January 2-6, 2023

Episode 1: A Nation Waits

Episode 2: The Allure of Everest

Episode 3: The Summit

Episode 4: Scoop of the Century

Episode 5: The Crowning Glory

*

All Quiet on the Western Front, directed by Edward Berger, 2022, available on Netflix.

1917, directed by Sam Mendes, 2019, available on Apple-TV

______________________________________

Barbara Demick (USA)

Winner of the 2010 Samuel Johnson Prize (the precursor to the Baillie Gifford Prize) for Nothing to Envy: Real Lives in North Korea

Nothing to Envy is a book that grew out of frustration. It was conceived while I was covering the Korean peninsula for the Los Angeles Times. For the first four years on the beat, I was unable to get a visa to visit North Korea, and that made me obsessed. Trying to recreate for the experience of being there, I interviewed every North Korean I could find. The numbers were probably in the hundreds since I was at the time living in Seoul and frequently visiting China. Out of my interviews emerged this work of narrative nonfiction about the lives of ordinary North Korean—their love lives, passions, sense of humor, along with the terror and deprivation.

In much of the coverage, I thought, North Koreans had been demonized as brain-washed robots marching in step with their nuclear-armed leadership. Since the book was published in 2010, North Korea has gotten a new leader, Kim Jong Un, but the fundamentals haven’t changed. North Koreans are trapped in a country they can’t escape, deprived not only of food, but contact and information from the outside world. I think the book has enduring relevance beyond North Korea because it is really about the psychology of people living in a repressive regime. The lessons I learned this book informed my subsequent writings about China and Tibet.

Until Nothing to Envy came out, most of the books about North Korea focused on the Korean War, the Kim family dynasty and their relations with Mao and Stalin, weapons of mass destruction, etc. I think publishers paid little attention to North Korean people because they were powerless and therefore seen as irrelevant to the larger geopolitical equations that impacted the West. It wasn’t easy to get a book about North Korea. I’m proud that the success of Nothing to Envy helped several North Korean defectors to get their own memoirs published afterwards.

Of these memoirs, I like The Girl With Seven Names (2015) by Hyeonseo Lee. Novelist Suki Kim went undercover in Pyongyang as an English teacher and produced an extraordinary book about the mindset of the North Korean elite, Without You There is No Us (2015). My favorite book of the more recent books about North Korea is Anna Fifield’s The Great Successor (2019), a biography of Kim Jong Un that looks at the years following the death of his father Kim Jong Un in 2011. Serious North Korea followers and professionals follow NKnews.org, published out of South Korea. I also read 38north.org and its affiliated site, Nkeconwatch.com.

–Barbara Demick

______________________________________

Margaret MacMillan (Canada)

Winner of the 2002 Samuel Johnson Prize (the precursor to the Baillie Gifford Prize) for Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed The World (formerly Peacemakers: Six Months That Changed The World)

My book is about an event which may never be repeated—a huge peace conference including most of the world’s major leaders and which lasted for over a year. It attempted to deal with the consequences of a devastating world war, settle borders, and create a basis for lasting peace for the world. I became fascinated by the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 when I was teaching modern history because so many of the issues, from the fate of the Middle East, to the relationship of China and Japan to the West, which concern us now, came up then.

And the cast of characters was extraordinary: President Woodrow Wilson of the US, Prime Minister Lloyd George of Britain, Georges Clemenceau of France plus those such as John Maynard Keynes and John Foster Dulles who were in turn to become powerful and famous. I hope readers of my book may learn, as I did, how important the past is to understanding the present and how we might avoid making the same mistakes. In the years since Peacemakers was published, historians have explored further the impact of the peace conference on the non-European world or its economic consequences.

If you want to know more, I suggest the following recent books:

Patrick Cohrs, The New Atlantic Order: The Transformation of International Politics, 1860-1933 (Cambridge 2022)

Robert Gewarth, The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End (London, 2016)

Norman Graebner and Edward Bennett, The Versailles Treaty and Its Legacy: The Failure of the Wilsonian Vision (Cambridge, 2011)

Erez Manela, The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism (Oxford 2007)

Adam Tooze, The Deluge: The Great War and the Making of the Global Order, 1916-1931 (London 2014)

–Margaret MacMillan

______________________________________

Patrick Radden Keefe (USA)

Winner of the 2021 Baillie Gifford Prize for Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty

Read from Radden Keefe’s speech at the 2022 Edinburgh International Book Festival: “On the Opioid Crisis, the Sacklers, and the Unsavory Game of Philanthropic Reputation Laundering.”

“One evening last December I made a visit to London for a gala dinner at the National Gallery on Trafalgar Square. I had recently published a book, Empire of Pain, which was an investigative chronicle of three generations of the wealthy Sackler family. Known for their philanthropy, the Sacklers had become famous for making lavish gifts in the arts and the sciences, always with the stipulation that their family name be recognized in relation to this generosity; there were Sackler galleries and wings and lecture halls and libraries at countless prestigious institutions on both sides of the Atlantic, from Oxford University and the British Museum to the Smithsonian in Washington and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.”

______________________________________

James Shapiro (USA)

Winner of the 2005 Samuel Johnson Prize (the precursor to the Baillie Gifford Prize) for 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare

Read from James Shapiro on “Shakespeare, the Culture Wars, and the Movement for Color-Blind Casting.”

“The late 1980s and early 1990s were a time of the Culture Wars in America, waged in op‑eds, magazine articles, and in books like James Davison Hunter’s Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America, Roger Kimball’s Tenured Radicals, Ivo Kamps’s Shakespeare Left and Right, and Allan Bloom’s best‑selling The Closing of the American Mind. Shakespeare was dragged into the quarrel as rival camps fought over his place in the college curriculum.”

______________________________________

Craig Brown (UK)

Winner of the 202o Baillie Gifford Prize for One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time

Read from Craig Brown’s 2019 speech at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on “The Slippery Art of Biography.”

“One of the longest biographies of recent years, the ill-fated Philip Roth by Blake Bailey, runs to 800 pages. It takes a total of 31 hours and 46 minutes to listen to on audiobook. Roth was 85 when he died, so his real life ran to a total of 750,000 hours or so. Even the longest biography is but a tiny fraction of the life it is intended to chronicle.”