Meet the 2024 National Book

Award Finalists

Quick Questions for the Year's Best Writers, Poets, and Translators

The winners of the 75th National Book Awards—given every year in Young People’s Literature, Translation, Poetry, Nonfiction, and Fiction—will be announced next week in a ceremony hosted by Kate McKinnon at Cipriani Wall Street in New York City.

Ahead of the festivities, Literary Hub caught up with (almost) all the finalists to ask them a bit about their books, their reading habits, and their writing lives.

FICTION

‘Pemi Aguda, author of Ghostroots: Stories

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I don’t. I wait until I want to write, or until a deadline forces me back to it. In the meantime, I fill that space with reading.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Sula by Toni Morrison. Such Small Hands by Andrés Barba. The Door by Magda Szabo. The Vegetarian by Han Kang. Mariette in Ecstasy by Ron Hansen. Story collections by Lesley Nneka Arimah, Laura van den Berg, Yoko Ogawa, Diane Cook & Clare Beams.

How do you decide what to read next?

The intersection of friends’ recommendations, my own TBR pile, and what I’m comfortable letting influence my writing at the time—through themes or language.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

Painting my nails so they look sexy for the keyboard.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

Write what you know might be the best and the worst? Worst, because it is constraining. What if I want to write into the unknown? Best, because sometimes I can’t get moving until I am implicated somehow, until some self-knowledge becomes an engine, even if the work eventually moves past it.

Kaveh Akbar, author of Martyr!

What time of day do you write?

I like to write early in the morning before I’ve done anything else, while my brain is still gummy with dream logic.

What’s worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

A bona fide genius, this guy who fluently spoke several dozen languages, once told me, “The key to being thought a genius is to never be seen doing anything you’re not already good at.” It may actually be good advice if your goal is persuading the world you’re a genius, but it strikes me as a terrible way to live.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

I had a pivotal high school English teacher named Steve Henn. Mr. Henn was the one who first sent me home with a stack of poetry books, who read—with earnestness and grace—hundreds of my awful teenage poems, off the clock. He afforded me the dignity and seriousness I had no idea I was desperately craving. Even years after I’d graduated, Mr. Henn was never too busy to recommend a new book, or talk with me about one I’d just read. His generosity to me, when it could do him absolutely no good, is a bedrock gratitude I will gratefully spend my life trying to pay forward.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

My personality is more indebted to The Simpsons than any other book or movie or album or show or art thing. Nightly Simpsons reruns were my introduction to Kubrick, to Shakespeare, to Seurat and Carmen and Star Wars and the Smashing Pumpkins. I knew the whole plot of the Odyssey, of Rear Window, of Hamlet, years before I ever actually encountered the original texts.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

I spend hours every day walking my dog. Some people have crosswords or yoga or knitting; I walk with Galilee.

Percival Everett, author of James

Who do you most wish would read your book?

I’m happy to have any reader. I wish my book would be read by people who don’t usually read, people whose sensibility is different from mine.

What time of day do you write?

No particular time. I often work late because it’s quiet.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

There’s no such thing.

What’s the worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

“Write what you know.” I don’t know much.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

I have had many strong influences. There is no one person. My father. My high school librarian. Robert Coover. My agent, Melanie Jackson. My wife, Danzy Senna.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

That I write everything with a pencil.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Music.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

Lewis Carroll’s Symbolic Logic. I was very young. My father and I read it together. It was like a game.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Many. Tristram Shandy, The Way of All Flesh, If He Hollers Let Him Go.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

Everything.

How do you decide what to read next?

The book finds me.

What’s one book you wish you had read when you were young?

Many of the children’s books that I have read since having kids. I didn’t read kid’s books growing up. The Phantom Tollbooth.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

Horses.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

A large animal vet or a carpenter.

Miranda July, author of All Fours

Who do you most wish would read your book?

I’ve gotten a few messages from women who read the book and then asked their husbands to read it and while I didn’t have this in my head while I was writing, I am now quite taken by the stories of what happens to the relationship after they both read it. This all hinges on not being the woman who wrote the book—the book becomes “the third thing” to safely discuss. I do this with other books.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I try to be like a great mom and just pour the love on. And not just love for myself, but also for music, for other people’s books, for nature, humans, life. The world is gigantic and alive so nbd if you’re not producing at this very moment, just move around in the glory of the world, drink it in and be free. So much of writing is just tending to the garden so things will grow (yep, I use the garden metaphor all the time. I’m always telling friends to tend to their garden. Or refill their cup. No need to be original in this territory!)

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I don’t drink coffee, never have. But during a rough patch of All Fours I would buy a coffee in a bottle at the start of the week and have one gulp every day and then put it back in the refrigerator. My friend Isabelle gently pointed out that probably I should throw the bottle out if it had been two weeks and I was still working on it. I thought it just stayed good forever, like soy sauce.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

Maybe The Secret Garden or The Little Princess, books where a bereft girl makes a safe, secret, beautiful world for herself.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

I mean this is a case of save me from myself: I am forever accumulating tips and tricks in the realm of nutrition, skincare and daily functioning. I do realize that, especially as a woman, it’s a real achievement that I get asked about my work, not my tips and tricks, but they are always on the tip of my tongue. As a child I was an avid reader of “Hints From Heloise” in the newspaper.

Hisham Matar, author of My Friends

What time of day do you write?

In the morning, because that’s when I am more audacious, and then again in the afternoon, because that’s when I am more critical.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I’ve never had a writer’s block, but I do sometimes get weary or lazy or a little lifeless. And what I do then is I copy out what I had written the day before, and do so by hand, which slows everything down, and before I know it I’m editing and rewriting and going on further with some new sentences. Having said that, I think sometimes it is good to stop writing and go do something else.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

The practice of a social life that is neither premeditated nor transactional. I have a deep faith in such exchanges, with strangers and people we know well. Any vision of life that is not passionate about this sort of free human connection leaves me cold. And I have learned at least as much, if not more, from the people I’ve met than from the books I’ve read.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

A couple of hours spent on the phone at midday speaking with friends or members of my family. Never video calls. The phone is far more intimate.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

When I was a boy I worried about things ending. Perhaps this is why I found the Arabian Nights addictive. They were frightening, because of the risk of execution that Shahrazad faces at each break of dawn, and consoling, because of her ardent ability to never run out of stories to leave her would-be executioner wanting to know what happens next.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

Immediately on graduating from university I went and trained as a stonemason, then worked as one for a year or two. I still miss the clean feel and smell of stone, the way it is always pulling inwards, and the time it takes to fashion it, and the way that changes your sense of time. But I wasn’t very good at it.

*

NONFICTION

Jason de León, author of Soldiers and Kings: Survival and Hope in the World of Human Smuggling

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

Best Advice: Read your work out loud to yourself as part of the editing process. This was a game changer for me because there is nothing more humbling than hearing how dumb your supposedly well-crafted sentence sounds when read out loud.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

My buddy Willy Vlautin is a writer and musician whose work has long inspired me. I draw a ton of inspiration from his books and albums and I go to him for pep talks when I’m feeling terrible about myself and need someone to tell me it’s going to be ok. I called him for advice once when I was struggling with a particular chapter of my first book and he told me, “You can’t fix a trainwreck without a train.” So I went back to building my train. I live by that advice now when I have writer’s block.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

I couldn’t imagine writing in a world without Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska, Ghost of Tom Joad, and Devils and Dust or Jason Isbell’s entire canon.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Sing, Unburied, Sing and Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward. Blood Meridian and Cities of the Plain by Cormac McCarthy. Lean on Pete by Willy Vlautin. Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

I always want to talk about the book that I will someday write about the LA punk-funk-ska-rock-reggae band Fishbone and why culturally, politically, and musically they are the most important band of the late 1980s and early 1990’s.

Kate Manne, author of Unshrinking: How to Face Fatphobia

Who do you most wish would read your book?

I’d love it if both those who are constantly trying to lose weight would read it, obviously, but also for those who are thin and feel superior on that basis. The message that we are not in minute control of our bodies might be bracing and confronting and comforting to all of those people, and not necessarily in predictable ways.

What time of day do you write?

I’m not an early riser, but writing for a few hours as soon as I get up—before answering any emails or making breakfast—is a routine I swear by. I also enjoyed writing much of this particular book, Unshrinking, during my young daughter’s naptime. It was a few hours where she needed me close by (I called it “nap support”) and I couldn’t really move around a lot lest the noise wake her up. I just wrote guiltlessly and silently. It was excellent.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

The solution, I think, is rarely to keep trying to write through it. It’s to take a shower or a walk or a nap. Sometimes all three. I’ve also come to reluctantly accept that I only have about two good hours of writing in me per day. After that, if I keep at it, I find myself down rabbit holes.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I am sometimes perceived as hardworking and productive, but I sleep a lot and think I am much more creative and effective after at least ten hours of sleep. I don’t always get it, of course. But I try my very best to meet my (admittedly) high sleep needs in order to be at my best, both intellectually and emotionally. Another aspect of my writing routine that is a little bit eccentric: I read my work aloud a lot, to make sure the sentence rhythm sounds right. I also listen back to it on text-to-speech for the same reason. Reading through it, even printed out, is just not enough for me.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

I love writing and, honestly, I procrastinate from doing other things—like administrative tasks—by doing it. I never feel more grounded or alive than when writing. Embarrassing but true.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

Be a food writer. A cheat’s answer, to be sure, but I would love that. I’ve also wondered if I missed my calling as a journalist.

Salman Rushdie, author of Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder

What time of day do you write?

I do it more or less like an office job. I’m not good early in the morning. I used to like writing at night but these days I just want to sleep.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

My old history professor at Cambridge told me, “Don’t write history until you can hear the people speak. If you can’t, then you don’t know them well enough and you can’t tell their story.” Excellent advice for novelists too.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Ulysses, Song of Solomon, The Code of the Woosters.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

Watching baseball. I hate it when the season’s over. (Now.)

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

I wanted to be an actor. I don’t think I’d have been very good. So probably I’d mostly have been unemployed.

Deborah Taffa, author of Whiskey Tender: A Memoir

Who do you most wish would read your book?

Hearing my elders say they liked Whiskey Tender when I went to Laguna Feast Days this September was incomparable. If they hadn’t liked it, I would’ve been inconsolable. At the same time, I’m aware that my family has a stake in the histories. It’s another thing for a dispassionate stranger to pick up the book, read a few pages, and find herself pulled along by the language. The writer in me hopes to find readers despite rather than because of the topics. I care about the histories, but I am also trying to create art.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

In grad school I took a class in performance autobiography. We studied Spalding Gray, Eve Ensler, et cetera. I recognized the art form as oral storytelling, a practice I’d witnessed all my life in Indian country. Suddenly, my childhood and academic worlds merged. Whether sitting around a fire, or sharing during ceremonies, my elders were always trying to understand the world via stories. I’d been raised on family tragedies, dreams, and myths, and I realized that oral storytelling had given me a voice. My father especially had modeled the way stories could rearrange and restore a life.

What’s one book you wish you had read when you were young?

1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, by Charles C. Mann. If Indigenous accomplishments in botany, medicine, astronomy, and architecture had been celebrated in my high school classrooms, it would have bolstered my sense of self-worth. The incredible contributions of Native people should become the focus in schools. Too often, the lens of illness, death, and war—an incomplete and condescending account—take up the bulk of curriculums.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

First, the way the book reads like a novel with history woven in, which makes it difficult to shelve in bookstores. Second, the contradictions in the environmental story. Lastly, the broader regional themes vis-à-via Indigenous reclamation. I’ve encountered many Hispanic readers who connect with my mother’s story. They become teary eyed when they tell me they’ve been called “pretendians” for wanting to reclaim their tribal lineages. I hope Whiskey Tender reminds people that the Americas are Indigenous. When we eschew borders and support each other, our voices gain unity and power.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

When I was young, I cleaned rooms and waited tables. I liked the movement; the way I could observe people without being seen. I saved money for tickets to Indonesia and Senegal, where I ate street food and slept on beaches. If I hadn’t met a partner who steered me toward a loving home, I’d might still be on the road. If I wasn’t telling stories about the world, maybe I’d be experiencing it more.

*

POETRY

Anne Carson, author of Wrong Norma

What time of day do you write?

All times. Ideas are harlots.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

“Before writing any of my works, I walk around it several times, and I get myself to go with me.” –John Cage

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

Start in the middle.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

Mrs. Cowan, the high school Latin teacher who taught me ancient Greek on my lunch hour.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

Homer’s Iliad.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Homer’s Iliad.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

Homer’s Iliad.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

The badness of interviews.

Fady Joudah, author of […]

Who do you most wish would read your book?

Anyone forty years after I die.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I do not tackle ghosts.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

Definitely it’s my upbringing in Arabic.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Those I peppered with marginalia, highlighted excerpts, underlined passages.

Diane Seuss, author of Modern Poetry

Who do you most wish would read this book?

All of them are dead (my dad, Mikel, who was central to frank: sonnets and the person on its cover, John Keats) except one—my first love, when I was barely a teenager, who jilted me good, and would not read a book of poems if you paid him.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

It was a holy trinity of favorite books and they all landed at the same time: A book of Grimms’ fairy tales, bought for me by a family friend when I had chicken pox; a Better Homes and Gardens book on pregnancy and birth; and an illustrated bible. I returned to a single image in each book. In the Grimms, the story “Bluebeard,” when the young wife discovers her wealthy husband’s secret room full of his previous wives’ bodies, hanging on hooks; in the pregnancy and birth book, the description and illustration of what to do about inverted nipples; and in the illustrated bible, the drawing of wicked women drowning in the great flood, and Noah’s ark just perched there on the surface of the water, watching. I loved the garish intensity of each, and the feeling that came with trespass. Each was an object lesson in the dubious joys of inhabiting a female body.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

Best writing advice: “Take your poems out from under the bed, Emily Dickinson!”

Worst writing advice: “Take your poems out from under the bed, Emily Dickinson!”

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

The Price is Right. It’s a daily lesson in America’s economic class system. And I love it when people who live in the desert are thrilled about winning a power boat. It’s capitalism’s Sodom and Gomorrah. My son’s reaction is always the same: “Sell that shit!”

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your literary education?

My mother. Her parents would not pay for her to go to college after high school, likely because of her gender. They were barely working class, but were able to cover her younger brother’s college education. They were willing to pay for her to go to secretarial school. She attended a couple of classes, and then skipped the rest, spending those hours in the Potawatomi Greenhouse in South Bend, Indiana. She met my dad, just home from his time in the Navy during World War II, where he hid in the boiler room during battles.

They got married after knowing each other for a few months, he took the GED, and then he went to college to get a teaching degree. After they had my sister and me, and he got a job teaching industrial arts in a small high school, driving a bus before and after school for extra money, he became ill, probably from the asbestos in the belly of that ship where he hid, and died when he was 36, and my mother, 34. It wasn’t long after the last shovel of earth was tossed on his coffin that she decided to get a college education.

“Why did I do that?” she asked me the other night on the phone. “How did I have the guts? How did we make it financially?” It took her five years of driving to the university extension very near that greenhouse where she used to wander, to finish her degree in English, with a teaching certificate. In those five years, she brought books into our house. She made a bricks and boards bookcase in the living room, which slowly became filled with the texts she somehow paid for. Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Finnegan’s Wake. Mrs. Dalloway. Heart of Darkness and Nostromo. Moby Dick. And one small, narrow volume with a cherry red and blossom white cover: Modern Poetry. I wasn’t yet old enough to read the books, but it didn’t matter. She read them. My mother. She wrote about them, on a manual typewriter that she told me is still in the back of the closet in her bedroom. She typed long into the night, keeping my sister and me awake, in that crackerbox house where she still lives. Must I be explicit? She permitted herself, and therefore permitted me.

Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, author of Something About Living

What time of day do you write?

For many years, when I had young children at home, I wrote in the mornings when they were at school or occasionally very late at night. I have less of a routine now, but I still have a soft spot for that stretch of morning, the second-cup-of-coffee hours, after the hectic energy of family rushing off to their worlds, when the house settles into a quiet that feels inviting and generative.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

The best has been to walk away from a text that is tormenting me. To give writing time and space to breathe. This gets easier with age, You learn that a text has a kind of growth cycle and your initial version of it develops on the page and in your mind and on the page again and so on.

Who is the person or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

My writing is shaped by a childhood in which my family moved back and forth between and within cultures and languages. It felt difficult sometimes, but I think of it now as an incredible gift. Entering new spaces where I had partial access, most often through language, but was still an outsider, taught me about the power of paying attention, and about the ways a self is constructed.

The place that had the most significant impact on my writing was my maternal grandparents’ home in Amman, Jordan. It was the one constant in childhood—I spent summers there among my cousins, running around a garden that was our private paradise. My grandfather was a writer, and he would sit at the dining room table every morning and jot down a draft of his weekly newspaper column amidst the noise and commotion of at least a dozen grandkids. Almost every room in the house had multiple bookshelves stocked with volumes of fiction, poetry, essays and criticism in many languages, and the days were punctuated by the meticulous routines of my grandmother, an elegant woman from Damascus whose cuisine and hospitality remain my example. Loved ones were always arriving, being welcomed, gathering to tell their stories. The sounds, textures, and weather of family in that time and place anchored me in the world and shaped my writing.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

I remember reading a book called Hameed Al Ballam in grade school, a story of a young Iraqi fisherman who dies resisting the British occupation of his homeland. I loved it and it broke my heart.

Which books do you reread?

So many! My middle daughter and I are big fans of Elena Ferrante’s novels and we plan to reread the entire Neopolitan quartet over winter break. I often return to In the Heart of the Heart of Another Country by Etel Adnan. This year, I’ve been curating a year-long subscription of Palestinian poetry for Open Books, Seattle’s poetry bookstore, so I’ve had the opportunity to reread some of the books I admire most, including Mahmoud Darwish’s Memory for Forgetfulness, which feels electric in the ongoing genocide in Palestine.

*

TRANSLATED LITERATURE

Bothayna Al-Essa, author of The Book Censor’s Library

Who do you most wish would read this book?

My three children.

What time of day do you work?

I am not a morning person, but I work in the mornings, because it’s the most quiet time of the day. Sometimes I work in 2 shifts, mornings and afternoons. In a good day, I would write for 9 hours.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I change the genre; I often go to writing something childish or about childhood.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

All are as good or as bad, depending on the context.

What part of your writing or translating routine do you think would surprise your readers?

Nothing surprising. I’m a routine person, boring and extremely introverted. I basically daydream, write, and have a walking break.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

I had a collection of illustrated classics and fairy tales as I child. I fell in love with all of them. They are my treasures.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Mostly something written by Gabriel Garcia Márquez.

Sawad Hussain, translator of The Book Censor’s Library

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

Let me count the ways!

Washing dishes, researching new books to pitch (when I should really be translating my current book under contract instead), watching the world go by from my front window, watching lectures given by other translators or voice noting family and friends.

What part of your translating routine do you think would surprise your readers?

That up until I had my son four years ago, I wrote all my translations out by hand. It definitely took longer, but I also felt that the quality of my translation required less self-editing later on in the process. I would use old office diaries to write my translation in, and different colors based on how I felt on the day. I sincerely wish I could go back to working that way, but with a full-time office job and a child, it’s pretty much impossible.

These days, if I’m struggling with a particular passage of a book, I do end up handwriting it. There is something so ingrained in me from childhood about being creative whilst physically writing. The first few attempts I had at typing translations directly into English onto a computer were quite painful for me and lackluster. I feel like I’ve finally gotten more into a rhythm with typing these days.

If you weren’t a translator, what would you do instead?

I would be the first Pakistani 800m runner to medal in the Olympics.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your literary education?

My family—both immediate and extended. Just the amount of books we have in the Hussain households combined is ridiculous. We used to think my mother had gone a little bit too far in keeping a lot of our childhood books, but now that my son is reading them, it makes my heart so full! That he can actually touch the pages of books I used to spend hour after hour with. The sight of my mother, my father and my sisters reading at all times, it just cemented for me how books are a part of our lives that we can never abandon.

How do you tackle writer’s (or translator’s!) block?

I usually end up reading something which is extremely far removed from what I’m working on (whether in theme, form, style etc.). For me, block is usually associated with fatigue of some kind—physical, or just fatigue from the characters that I’m crafting. I have definitely suffered from translation burnout and am learning to take better care of myself whilst balancing the rest of my responsibilities and relationships.

Ranya Abdelrahman, translator of The Book Censor’s Library

How do you tackle writer’s (or translator’s!) block?

I put the text aside for as long as I can afford to. Sometimes a phrase I’m struggling with will come to me when I’m not actively thinking about it, or will seem glaringly obvious when I go back to the translation after a break.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

For my eighth birthday, a friend gave me The Little White Horse by Elizabeth Goudge. I must have read it hundreds of times. I loved the lyrical fairy tale with its intrepid heroine and colorful characters, both human and animal. And those names—Miss Heliotrope, Marmaduke Scarlet and Loveday Minette. I last read it in my early teens, but I still have my beloved copy of the book.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

Playing word games like Waffle, Wordle and Al-Wird (which is similar to Wordle, but in Arabic).

How do you decide what to read next?

I used to explore bookshops for new reads, but now I depend more on podcasts for recommendations. The Bulaq podcast is a great source of information about Arabic books. For English books, I listen to BBC World Book Club and indulge my love of crime novels and thrillers by tuning into the hilarious Red Hot Chilli Writers podcast.

If you weren’t a translator, what would you do instead?

I’d either be a librarian or go back to writing code.

Linnea Axelsson, author of Ædnan

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

There isn’t one specific painting, but I find it hard to imagine not engaging in paintings, which has been a part of my life for a long time. It is such a particular way of looking, a kind of listening with your eyes. The notions of time and concentration in front of an image, is quite different from how you experience time and concentration as a reader. I need both.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Anton Chekhov, Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, Toni Morrison, Elizabeth Bishop, Ingeborg Bachmann, those are some of the writers I get back to again and again.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

I like to look at sewing patterns and make the garment or object in my mind. If I don’t do that and try to escape work, I read news papers online.

How do you decide what to read next?

I think my reading pattern is related to what I’m writing and what is on my mind in general at that specific time.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

If I wasn’t writing, I hope I would be some kind of carpenter. Wood is a beautiful material. It has a kind of soft resistance, it gives, but stays firm. In language there is so much potential depth, you have to create the useful resistance yourself, through shape, for example.

Saskia Vogel, translator of Ædnan

What time of day do you work?

Morning writing, before my child wakes up at 7:30. It’s the best time for that practice for me, and it’s a sliver of time I know can be just mine. I translate the rest of the work day.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

I was so worried about my writing life when I realized I wanted to try and have a child. The story I carried with me, the story I gleaned from my environment, was that parenthood and writing were incompatible. I feel like I polled every writer I knew with kids: what’s it like? One writer told me that the page is the only place where everything is where she left it and can be exactly what she wants it to be. Her conception of the page kind of cured me of writer’s block by reframing the page as a haven. I now look forward to meeting the page each time I sit down to write. But there’s a caveat, for both writing and translation: I have to allow my first draft to be awful. It always is. I have to let the draft be awful first for it to ever get good.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

Tonight, I was meant to revise a translation. I did my nails, traded voice notes with some dear friends who I do that with, and then added some second coats of paint to the houses on “Halloween Street,” a milk-carton arts-and-craft project my co-parent and I are doing with our child before Halloween. Then I did a number of bite-sized tasks for the Erotic Review, a London-based literary magazine Lucy Roeber relaunched this year and that we edit together. Ultimately I decided to get a good night’s sleep and revise the translation with a fresh head first thing in the morning. I did almost all of this in bed, trying not to stress about not doing the translation. I think I procrastinate when I feel overwhelmed. So really, the impulse to procrastinate probably means I need a proper break and some nourishment.

How do you decide what to read next?

For pleasure, a deciding factor is when one of my holds from the Los Angeles Public Library becomes available. I like how it’s a bit random in that way, because so much of my reading for work is directed. So this September, I was reading Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World when I was in Gothenburg, Sweden, during the city’s book fair which I always try to attend. I started reading it on my way to the launch of a Swedish translation of essays by Ailton Krenak, an indigenous leader from Brazil: Om Drömmen, Om Jorden: Idéer för att fördröja världens undergång (On the Dream, On the Earth: Ideas on How to Delay the End of the World), which I’ve been dipping into since then. Meanwhile, I’ve been carrying around Chamayou’s Drone Theory as part of the research for my novel-in-progress. My favorite “what to read next” comes at bedtime with my kid, him picking books from the shelf or me introducing him to my old favorites. He’s loving the Bunnicula series at the moment.

If you weren’t a writer or a translator, what would you do instead?

Paint. There’s almost nothing I love more than being close to color and communing with light. It’s visceral.

Fiston Mwanza Mujila, author of The Villain’s Dance

What time of day do you work?

It all depends on the text or book I’m writing. Some texts need daylight to germinate, others require the writer to graft away by night or at dawn. Some texts burgeon with silence, others with jazz or Congolese rumba. Some texts are born at midday, others late in the evening. Some texts mature before birth, others are spawned quite unexpectedly. I am one of those who considers that literary creation involves several stages of writing and rewriting which may occur at any hour. Sometimes it is not the writer who decides the rhythm of his writing but the characters who appear, who suddenly cry out to be born and live. Writing is like pissing. It can’t be planned. That said, I try to do my research or make notes during the day and write at night. Sometimes I manage to do so; sometimes—against my will—the urge to write upends the schedule.

Which book(s) do you reread?

I was born in a mining town that had very few libraries and bookstores in my day. The shortage of reading materials meant that me and my brother (teenagers both) read anything we could get our hands on: geography manuals, cookbooks, architecture titles, and the Bible of course, which I know inside out. Even today—out of force of habit no doubt—I still assiduously read the Bible along with works of psychology and philosophy, even when there’s no real reason to do so.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

If you want to write, above all learn to read, and read a lot. I think that’s the best piece of advice someone gave me at the start of my writing career. Reading not only expands your imagination, it enables you (sometimes unconsciously) to acquire the technical arsenal to devise a fictional world, develop characters, build a plot, manage suspense, hone your language, find your path . . .

Read other people. We’ve been writing the same book since the dawn of time. Everything’s already been said. As an author, you feed off others to reach yourself. Reading is the greatest nursery for literary creation.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I view writing as manual labor, like welding or artisanal mining. I always take a bath before writing and I do the same afterward. My texts swarm with bodies, of the people who work in the mines, the sweat, the noise, the odors. It’s like a bayou, crawling with microbes. I have this essential need to cleanse myself before and after the creative act.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your literary education?

The place from which you develop your reflections influences the act of writing. I observe the world and things from Katanga, my native province, and Graz, the city where I’ve lived for fifteen years. My grandparents are from the Kasai province. In colonial times, people from this region were recruited en masse to toil in the mines. That’s how a good many members of my family, on both my father’s and mother’s sides, found themselves in Southern Congo. Some drudged away in quarries, others worked for a railroad firm as welders or fitters. My grandfather was an excellent businessman. My maternal uncle has worked as a fitter for forty years. Watching him manipulate iron and fire is a moment of grace. If I hadn’t been a writer, I would have probably been a fitter, a welder or a storekeeper. I’m really interested in the issue of (post-colonial) violence and the working class.

Living and writing (in French) in a Germanophone space feeds my creativity and my relationship to the French language differently, for French is not just a former colonial language—with which my ancestors were subjugated—but also a personal, private language, a place of family memory. Consequently, the words acquire another tonality, another coloration from being perpetually confronted with German.

Roland Glasser, translator of The Villain’s Dance

What time of day do you work?

I find it almost impossible to do any worthwhile creative work before mid-afternoon. My “golden time” runs from around five to nine p.m. or even ten. It’s like my brain has no real “depth” until then. Mornings are good for admin, sometimes editing, or for reading, but not for producing anything of any creative value. But as the day progresses and evening beckons, the frontiers of my mind recede and my imagination expands; the lateral connections start to zip and flow, and everything falls into place.

As a singleton, this daily schedule was generally fine. As a father to two boisterous young boys, it’s somewhat more challenging, since I can’t take advantage of quiet daytime when they’re at school or at nursery to get work done. My own father (of blessed memory), also a writer, was the opposite. He’d be at his desk by 7 a.m. to deliver the night’s subconscious gifts to the page, pause for breakfast or to take my sister and me to school, then get back on it again until lunch—always at 1 p.m., always on the dot, always listening to the World at One on BBC Radio 4—before possibly a short stint in the late afternoon or early evening to wrap things up, print out a hard copy of the day’s endeavors and save them to floppy disk.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Cinema has been a massive influence on my creative life, including as a translator, probably because it is the most ‘total art’ after theater in terms of sensory and imaginative stimuli. Words, images, gestures, movement, sound, music, they coalesce into something ineffable. There is a deep hinterland of cinematographic experience that fuels me as I work, often subconsciously. It’s not by accident that I frequently listen to film soundtracks while I translate, often on a loop for days. As I write this, I have Cliff Martinez’s soundtrack for Drive in the headphones. Last week, it was Eduard Artemyev (Tarkovsky et al.).

My translation of Fiston’s first novel, Tram 83, was almost entirely composed to Edgar Rothermich’s glorious beat-for-beat and note-for-note reproduction of Vangelis’ OST for Blade Runner—a desert-island movie of mine if there ever was one. Possibly no surprise then that one of my very favorite books is Neuromancer by William Gibson. Sam Shepard and Bruce Chatwin also sit high in my pantheon. No coincidence either that all three share a certain considered lapidary style that often says the most through what is left unsaid. Virginie Despentes has been a more recent discovery—few writers have made me squeal quite as much with delight at the prose jewels which glitter on seemingly every page.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

Translation and curiosity go hand in hand. In fact it’s a professional pre-requisite. I am always looking things up: meanings, synonyms, idioms, turns of phrase, chronology of usage, details of socio-cultural references and historical events; checking the proper (and up-to-date) spellings of names and places. I dive down rabbit holes in the name of “research”, ending up some way beyond the point of apparent usefulness, although I like to think that you can never tell when some random bit of information will be plucked from the depths of memory and pressed into service many years hence.

Social media and YouTube provide much more prosaic channels for procrastination, too, of course. Still, I sometimes miss the old days, when the digital realm was a much more barren place. I recall one of my first translations—a book about the Tour de France yellow jersey (worn by the rider leading the race)—where, after every page I translated I would indulge myself by reading a whole chapter of Neal Stephenson’s wonderful Cryptonomicon.

If you weren’t a translator, what would you do instead?

I have a deep theater background. Little bit of everything (acting, production, stage management), but mainly lighting design. It has certainly informed my literary translation—I love translating dialogue, for example. And I suppose that if I hadn’t travelled so far in translation, I would probably have pushed on further in the theater world. Translation is something that I fell into a couple of years after I moved to Paris, when I needed the dough and naively assumed that a knowledge of two languages and a flair for writing were enough to make a go of it. Took me quite some time to really master the craft (and I’m still learning, every day). I often think that I wouldn’t mind doing something much more manual, perhaps outdoors, something that doesn’t engage the brain as much (or at least not in the same way), so that I could enjoy creating in my downtime, free from pecuniary pressures. But the grass is always greener, n’est-ce pas?

Yáng Shuāng-zǐ, author of Taiwan Travelogue

What time of day do you work (and why)?

我的小說創作進度最有效率的時段,是在午夜之後,通常會一直寫到接近清晨。這是經過白天種種轟炸(演講、開會、行政庶務一類的工作,以及運動與社交活動)以後,我相對能夠專心書寫的時刻。

The time when I’m most efficient with my writing is after midnight; I usually keep writing until dawn. This is the time when I’m relatively able to focus on my writing after miscellaneous bombardments throughout the day (by which I mean author talks, meetings, administrative tasks, exercise, social activities, et cetera).

How do you tackle writer’s block?

進入我的書房,面對我的電腦。運動。運動之後回到書房,繼續面對我的電腦。

I go into my study and face my computer. I go exercise. After that, I go back to my study and continue facing my computer.

What part of your writing or translating routine do you think would surprise your readers?

在小說書寫的同時,我會讓台灣流行音樂成為我的工作背景音樂。至今我仍然會聽周杰倫、孫燕姿在2000年代的幾張專輯。

I listen to a lot of Taiwanese pop music in the background while I write and work. Even now, I still listen to albums from the 2000s by popular artists like Jay Chou and Stefanie Sun.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

漫畫。我在成為小說家以前,曾經立志成為漫畫家。

Manga. Before I became a novelist, I aspired to be a manga artist.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

打手機遊戲。目前經常玩的兩款手遊是Disney Tsum Tsum與Candy Crush Saga。

Mobile games. Two that I’ve been playing a lot recently are Disney Tsum Tsum and Candy Crush Saga.

Lin King, translator of Taiwan Travelogue

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

The best advice I’ve received is to “start wherever it’s easiest to start”, which depends on each story and how the specific idea sparked. Sometimes the “easiest” place is the beginning, sometimes the end, and sometimes it’s a sentence floating in the amorphous middle.

What part of your writing or translating routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I often do first drafts (of both my own writing and translations) by hand—longhand.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

I’m pretty omnivorous. At the moment, the main content keeping me going are British detective/spy dramas (recommendations: Slow Horses and Endeavour), Japanese idols (WEST. and SixTONES), and political podcasts (mostly from Crooked Media and Vox).

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

Vacuuming. And adding things to online carts without buying them.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

Most recently, The Lost Daughter by Elena Ferrante, translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein.

Samar Yazbek, author of Where the Wind Calls Home

What time of day do you work?

أحب العمل عند الفجر بين الساعة الرابعة صباحا والثامنة، هو وقتي المفضل حيث أكون في كامل طاقتي قبل ان تبدأ رحلة العمل اليومية والانشغال بزحام الحياة، وهو الوقت المفضل لي حيث ينتابني ذلك الشعور بأني وحدي هنا أجلس وأراقب. العالم ساكن تماماٍ من حولي، وشخصيات كتبي تعيش، أراها وحدها تتحرك وكأن الفجر وحده من يسمح للشخصيات أن تتطور وتتحرك

I love working at dawn, between 4 and 8AM. This is my favorite time because I am at the height of my energy, before the routine of daily work and tasks starts with its hustle and bustle. I love this time of day because I feel like I’m alone in this place, sitting here and observing. The world is perfectly still around me, and my book’s characters come to life. I can see them moving about, as if dawn alone could allow them to evolve and move.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

أسوأ نصيحة سمعتها هو أنني يجب أن أترك إلهام الكتابة يأتي لوحده، دون خطة عمل وانضباط ونظام واجتهاد

The worst advice I ever got was that I needed to let the inspiration for writing come on its own, without any work plan, discipline order or diligence.

Which book(s) do you reread?

الكوميديا الآلهية لدانتي، كتاب ألف ليلة وليلة، موبي ديك لهرمان ملفيل، كل كتب حنة أرنت وجوديت بتلر وكتب آخرى

Dante’s Divine Comedy, A Thousand and One Nights, Melville’s Moby-Dick, all of Hanna Arendt’s books, Judith Butler, and more.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

لم يحصل هذا الأمر معي، فأنا ومنذ سنوات طويلة، أجلس بانتظام وأعمل، أحيانا عندما لا استطيع أن أكتب، وأصاب بحبسة الكتابة، أجلس أمام شاشة الكمبيوتر لفترات طويلة، وأكرر ذلك حتى أستطيع الكتابة هذه احدى طرائقي !

This never happens. I have been sitting regularly at my table and working at my books for many years. However when sometimes I am not able to write, or when I’m facing a writer’s block, I sit in front of my computer screen for long stretches of time, again and again, until I am able to write again. This is one of my tricks!

How do you decide what to read next?

هذا يعتمد على عملي الصحافي وكتبي التوثيقية عن الحرب وعن الذاكرة، هي من تحدد طبيعة قراءاتي، أيضاً اهتمامي بالقضايا النسوية يشكل مصدراً لقراءاتي، لكني وبشكل يومي أقرأ الرواية والشعر، هذا مثل الهواء والتنفس لي. وأتابع ما يُنشر ويترجم في العالم

This depends on my journalistic work, and on my documentary books on war and memory. This is what determines the nature of my readings. My interest in the causes of feminism is also a source of references. However, I read fiction and poetry on a daily basis. This is like breathing to me. And I follow what is being published and translated in the world as well.

Leri Price, translator of Where the Wind Calls Home

How do you tackle writer’s (or translator’s!) block?

Giving myself deadlines works best. And thinking about my bills.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

“Just get on with it.” (Depending on my mood, this could be advice of either kind.)

Which book(s) do you reread?

Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino (trans. William Weaver). That book is a jewel. But I usually end up re-reading everything eventually—I’ve found very few books that I don’t want to revisit. I just bought Your Wish is My Command by Deena Mohamed (trans. the author) as a gift for someone and it’s stayed on my mind, so I suspect that will be next.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

It used to be Twitter (RIP), but now I use Ask a Manager and Captain Awkward for my drama fix and ebay for mindless scrolling. I also have a very elaborate spreadsheet that I use to track work progress and I love updating that in as much detail as possible, preferably adding in percentage calculations and other useless bells and whistles. Perhaps I’ll start using it to generate charts.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

It has taken me a long time to read Alaa Abd El-Fattah’s You Have Not Yet Been Defeated (trans. a collective) because I am flooded with rage every time I pick it up. What a waste of a mind, and to have lost so many years with his son is a tragedy. On a lighter note, I started reading Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet in Ann Goldstein’s translation about five years ago, but was so incensed at the protagonist for her behaviour at the end of the third book that I never read the fourth. I still don’t know how it ends.

*

YOUNG PEOPLE’S LITERATURE

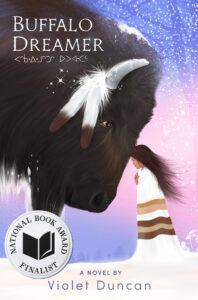

Violet Duncan, author of Buffalo Dreamer

Who do you most wish would read your book?

I hope that a young person who has never heard of the Indian Residential School System reads my book and thinks, “Why have I never heard about this before? The main character, Summer, is my age. Her grandfather went to this school at the same time my grandparents attended school. This did not happen so long ago that it is ancient history.” Take that question and bring it to their teachers, caregivers, or friends and start a conversation about how the Indian Residential School System can be discussed in a positive way.

What time of day do you write?

I try to write anytime I have free time. I wear many hats (as many do) as a mom, manager, writer, and performing artist, and I try to stay active on social media, which can be another little job. It’s not unusual for me to write while we’re on the road going to a performance or a game; I actually get my best work done when we’re on the road.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

My children are incredibly inspiring to me. They remind me of the direction our society is heading in and what matters to them, which revolves around many things, from sports to education to the state of the environment. They also make me think about the future job landscape for educators, scientists, and artists and how the world will look when they’re adults. They inspire me to write about my own history and perspective on the world, as they are curious about how our Native culture intersects with modern society and how to navigate both.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I think what surprises others about my writing routine is how inspiration strikes. Sometimes, when I’m driving and chatting with my kids or husband, a whole paragraph that I’ve been struggling to write will suddenly come to me, and I’ll have to jot it down before I forget. I have notepads and pens everywhere—in my purse, the car, and even under the couch! I could use the voice recorder on my phone, but there’s nothing quite like seeing my words written down in my own hand to understand where I’m trying to go in the moment of writing.

How do you decide what to read next?

I always have a few books in rotation. There’s nothing worse than finishing an amazing book and not having a good backup book to lean into. So, I have a “read-in-bed” book, which is usually a comfort book I’ve read before, a book in my purse to read at my kid’s swim or basketball practice, and a book at home that is something new to get me to finish chores or emails, so I can treat myself. It’s a bit chaotic but in the best way.

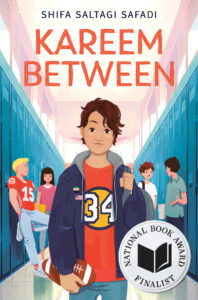

Shifa Saltagi Safadi, author of Kareem Between

Who do you most wish would read your book?

My younger self.

Growing up as a Muslim Syrian immigrant child in America during 9/11, and experiencing the aftermath of huge anti-Muslim rhetoric has been something I have grappled with my whole life. When it comes to Islamophobia, negative and hurtful experiences stem from other people’s anger at my identity. I cannot and would not change who I am. My Muslim faith is the most important part of myself. And I love who I am.

Grappling with trying to fix the world’s perception of me, trying to get people to accept who I am, as I am, has been a tough experience. Has probably fueled a lot of the anxiety I seem to constantly battle within my own mind.

Kareem Between is about not needing that external validation. Of rising above peer pressure. Of standing up for yourself and being confident in who you are.

Of being a proud Muslim Syrian American.

This is the book I needed the most as a kid. And I wish younger Shifa had it.

What time of day do you write?

I write in the morning, right after my morning cup of coffee has hit my bloodstream. It’s that time where my energy is the highest, my thoughts are the clearest, and my brain synapses are snapping and working.

If I do not get the time to write in the morning, it is likely not going to be a writing day at all for me. My brain tends to slow down in the afternoon, and by the time my kids come home from school, noise overwhelms my home (in the best way possible) and my writing brain is turned off in the favor of my mom brain.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

Writer’s block is a sign to me. It means that something is probably not working in my plot. As a plotter (a writer who outlines a book before writing it), I try to flesh out my characters and storyline way in advance of writing. And so then, when I draft, I have a template to follow. If I get to a scene in the book, and I face a block- it usually makes me re-evaluate my plot. And so, I end up re-plotting, going over the beats of the story and the threads of the character arc. I also step away.

After a few days—I am usually always able to get back to the story with a much better idea/revision, and the words start to flow again.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

My fellow older sisters—Muslim authors who have paved the way for me, and in particular, S.K. Ali and her debut book Saints and Misfits. It was the first Muslim book I read, and I related so strongly to the main character for a variety of reasons. I remember sobbing while reading. And it wasn’t the story line that made me cry the hardest. It was the fact that I had NEVER before read a book that reflected my own identity. It was the first time I felt seen. Subconsciously, I think, I had always internalized that Muslim stories did not have a place in the world, did not have an audience, would not be heard. Because I never read any. And I realized what I had been missing my whole life as an avid reader. Saints and Misfits inspired me to pursue my own dream of writing. It made me want to be that person for other young Muslim readers. To provide them with a mirror of themselves, and an inspiration. I want them to know their voices matter!

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

Reading books is my favorite pastime of all—and it’s what made me want to write in the first place. Reading fantasy is my favorite genre. I love getting swept away into a new world with magic and royal intrigue, betrayals and romance, and clever powerful female characters (bonus if there are dragons!!). I also love reading plots that I myself did not come up with. I always marvel at how clever authors are in their writing, and it makes my internal geek happy!

It’s also a great way to forget about my own life issues and just be immersed into a main character’s life and their fictional problems.

But I cannot read anything that does not have a happily ever after. Because my hope in this world and in my own life, is that happiness is just one more page flip away.

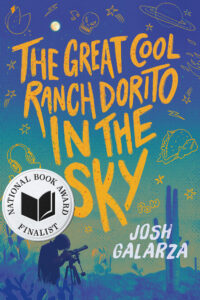

Josh Galarza, author of The Great Cool Ranch Dorito in the Sky

Who do you most wish would read your book?

While I believe this book is for everyone, I’m most eager to reach boys and men. One of my main avenues of research is in men’s issues and masculine performance, and I quickly noted that most of the literature and media we see for boys, whether intentionally or not, perpetuates patriarchal mores. While media for boys might prepare them for their place in patriarchal society, it rarely prepares them for the necessary, validating work of dismantling patriarchy in favor of a horizontal social structure.

I want to see patriarchy and white supremacy fall to the wayside—the sooner, the better—so in my writing, I’m attempting something really tricky. I’m asking myself, Can I write to and for boys—can I write honestly about their flaws, blind spots, and fears of being emasculated (can I validate the challenges they face in navigating patriarchy)—while also undermining all of the societal values that pen boys into a version of gender performance that harms them as readily as it harms women and fem people? In my books, you’re not going to find aspirational versions of boyhood. Instead, you’ll find very real, very messy boys struggling under the pressures they face, boys who are lucky enough to discover new ways to express and validate their masculinity.

Because I was in treatment for disordered eating while writing this book, I also recognized how alone I felt as a man suffering from bulimia and orthorexia. Though plenty of men experience anxieties about their bodies and engage in various forms of disordered eating, we’re not socialized to talk about such hardships or to even recognize them when they take root. How many men have even heard the terms orthorexia or muscle dysmorphia, for example? Not surprisingly, nearly all the media and research that helped me in recovery was created by and for women.

It’s incredibly important that men listen to the stories of women and strive to learn from them—doing so contributed greatly to my healing, not to mention that such work is necessary for men to become active feminists (with Mallory’s character, for example, I wanted to show boys how valuable women are as mentors rather than as potential romantic partners). But I couldn’t ignore the glaring void in media designed to speak directly to boys about these issues, media that might employ a boy’s own sensibilities. My goal, then, was to write a story that gives boys the tools and the permission to think differently about their bodies and the bodies of the girls and women in their lives.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

I was lucky enough to be mentored by a local legend in Carson City, Nevada, Marilee Swirczek, for the better part of a decade. I’ll never forget the first time she critiqued my work. She bracketed paragraph after paragraph and simply wrote “Why?” “Why?” “Why?” I was so green that I had no clue that maybe a novel didn’t need a whole chapter to characterize a town. But the magic of Marilee—and one reason so many local writers were utterly devoted to her—was that she could eviscerate a draft without ever making the author feel like he’d failed. Instead, her tough love felt just like that: love. And by God, did we all love her in return.

There are few gifts in my life better than having been believed in by Marilee. In my first semester with her, I recall staying late after class one night. After complimenting the pages I’d turned in the previous week and humoring me as I expressed my boyish ambition to debut as the next Chuck Palahniuk any minute now, she offered some advice I’m still following to this day: “Josh,” she said, “don’t quit your day job…” And then she tilted her head conspiratorially, raised her brow, and gave me one of her famous mischievous grins. “Yet.”

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

I am unendingly obsessed with television and movies—as a storyteller, I find film wonderfully instructive, each movie or episode a compact lesson in what to do or what not to do. And my tastes are all over the map, from the latest thought-provoking indie film to the basest reality TV. I’ll gave myself cultural whiplash by watching a movie like American Fiction or Past Lives immediately before jumping into an episode of The Traitors. My friends and family are so relieved that I’ve finished my recent binge-watch of Dance Moms.

I mean, I’m in my thesis year of an MFA program, so there is absolutely no excuse to watch Dance Moms for hours on end, but do you think that stops me? (And for the record, I’m team Maddie and team Chloe!) Don’t tell anyone, but when I’m finished with this interview, I’m actually going to start the show I’ve secretly chosen to fill the Dance Moms void: America’s Next Top Model. That show had so many seasons that I may not be a productive member of society again for at least five years. It was nice knowing you all.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you?

When I was in treatment, I read Patrick Ness’s A Monster Calls. It absolutely wrecked me, and I couldn’t be more grateful. The story follows Connor, a boy grappling with painful emotions regarding his mother’s terminal illness. One particular emotion—or more accurately desire—acts as the story’s linchpin, and its revelation is devastating. I won’t give it away for those unfamiliar with the book, but reading that story allowed me—a man in his thirties at the time—to finally acknowledge and own that I felt the same things Connor felt when my mother was slowly dying throughout my teens.

These were feelings I didn’t want to have, feelings I could never have acknowledged aloud back then. But as a man trying to heal, whenever something triggered me, I’d try to honor those emotions, make space for them and pay close attention to them. I’d take notes in the journal I used for therapy. Like most men, I struggled to access and understand my emotions for many years, so moments like these were opportunities to interrogate myself and my past, clear indicators of where I still had work to do in processing trauma from my youth. I’ve read all of Ness’s work since then, and I can’t recommend him highly enough.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

So far, I’ve been pretty lucky in academia to find balance between my three loves: writing, teaching, and printmaking. While I’m succeeding most apparently with my writing (and it’s consuming my life a little bit because of it!), if I had to choose just one thing to do for the rest of my days, it would actually be my visual artist’s practice. I was a Montessorian in my first career, and Dr. Montessori referred to the hand as “the instrument of the mind.” I thought of that adage all the time when I was in treatment and actively using my artist’s practice to help me heal.

I’m never so connected with my spirit as I am when getting dirty with ink or wielding cutting gouges. Nothing calms and energizes my soul like setting lead type for a letterpress project. The physicality and type of attention involved can’t be reproduced while writing, as important as writing is to me. Much of my work as a printmaker and book artist requires access to etching presses and Vandercook presses, these rarified spaces people in my discipline inhabit. It’s my dream to end up in a professorship someday that affords me that ease of access.

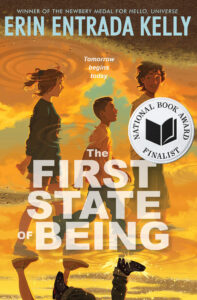

Erin Entrada Kelly, author of The First State of Being

What was the first book you fell in love with?

The Very Worried Walrus by Richard Hefter. It’s the story of a walrus who wants to learn how to ride a bike, but worries about all the disasters that could befall him. The Very Worried Walrus was part of the Sweet Pickles collection, a series of children’s books that were very popular in the 1980s. It was my favorite book in the series. I related so much to that walrus. I worried all the time when I was a kid. Sometimes my worries kept me up at night. Every time I read that book, I was reminded that there were other people (or walruses, as the case may be) who were just like me.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

There are so many things I’m interested in, but if I had to land on one, I’d be a teacher. I love teaching. I could see myself teaching full-time in a college classroom, but I could also see myself teaching middle school—sixth grade particularly.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I don’t really experience writer’s block. If anything, I have the opposite problem: too many ideas rattling around in my head and not enough time to write them. I spend a lot of time writing in my head before I ever sit down with a notebook, so it’s rare that I don’t know what to write. It’s even more rare that I don’t want to write. Writing is therapeutic for me—I don’t know how I would function without it.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

“You have to write every day.” That’s the worst piece of writing advice I’ve ever received. For some, it’s not possible to write every day. Years ago, I was a young single mother, working full-time and going to school, and it just wasn’t feasible that I would have the emotional or mental capacity to write every day. Each writer has their own process. Some write every day. Some don’t. You have to do what makes sense for you, your creative process, and your lifestyle.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

The importance of supporting, uplifting, and celebrating other authors—especially marginalized voices who are being actively suppressed right now through book bans and soft censorship.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you?

I read The Good Girls: An Ordinary Killing by Sonia Faleiro this summer and I’ve thought about it every day since. It’s narrative nonfiction about the deaths of two teenage girls—Padma and Lalli Shakya—in Badaun, Uttar Pradesh, India. The book is emotionally difficult, but I was completely transfixed by the girls’ lives, the reaction to their deaths, and the sociopolitical landscape of India. Sometimes I fall asleep thinking of Padma and Lalli. That’s the power of books. Here I am, thinking of two teenage girls who I have never met, who live in a country I’ve never been to, whose world is so different from my own, wishing they’d had a better ending.

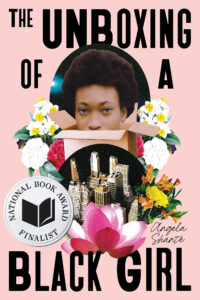

Angela Shanté, author of The Unboxing of a Black Girl

Who do you most wish would read your book?

I hope every Black girl and woman who can get their hands on the book will read it. Facts, I wrote The Unboxing of a Black Girl specifically for them. I’m happy (and hoping) that with the nomination of the National Book Award, many more will be able to do so.

What time of day do you write?

I don’t have a specific time that I write. I’ve always been a working creative, so I write when my schedule allows. It can be tricky balancing it all, but I use blocks of time in between teaching, during the weekends, or sometimes early/late into the night to chip away at different projects I’m working on.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

The creative mind of Quincy Jones. If you follow me on social media or are familiar with any of my books you know how much I adore him. His contribution to Black culture has shaped the way I think as a creative and molded me as a storyteller. With his recent passing, I’ve been revisiting his work, listening to his music, and just reflecting on his impact on my life. I mean, there is literally a poem titled, “I Was Obsessed with Quincy Jones Growing Up” in The Unboxing of a Black Girl. LOL.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

When talking about The Unboxing of a Black Girl, I often want to talk about craft; specifically the choice between form and function in the book. I’m a bit of a nerd and weirdly attracted to experimental storytelling so aside from talking about the big themes in the book I want to geek out about haikus and new poetic forms I’m playing around with.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

That’s an easy one, I’d be back where I started… in the classroom.