Meet National Book Award Finalist Shane McCrae

The author of In the Language of My Captor on poetry and persona

The 2017 National Book Awards (also known as the Oscars of the literary world), will be held on November 15th in New York City. In preparation for the ceremony, and to celebrate all of the wonderful books and authors nominated for the awards this year, Literary Hub will be sharing short interviews with each of the finalists in all four categories: Young People’s Literature, Poetry, Nonfiction, and Fiction.

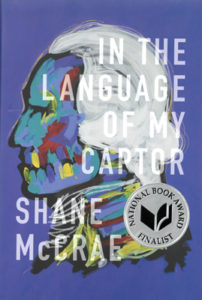

Shane McCrae’s In the Language of My Captor (Wesleyan University Press) is a finalist for the 2017 National Book Award in Poetry. McCrae is a flexible, experimental poet investigating the way history lays over (and under) the present moment; francine harris described his fifth collection as “a masterful hybrid that at once revels in the lyric and mocks it for its failures. What good is knowing the language of the oppressor, the jailor, In the Language of My Captor seems to ask, when articulation can’t enact liberation? The voices in this book create a landscape, indeed a village, haunted by abandon, intrusion, imprisonment and determinacy.” Literary Hub asked Shane a few questions about his book, life as a poet, and how it feels to be a finalist.

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

My partner, Melissa. She and I have different sleep schedules, and so I had to wait a few hours until she woke up. Those were hard hours. But I wanted her to be the first person I told.

What time of day do you write (and why)?

I have no set time—I try to be available for poems as often as possible, and sometimes they occur to me just as I’m about to go to bed, and sometimes they occur to me as I’m walking to work, and sometimes—more often than at any other time, I think—they occur to me in the shower. I always have a notebook with me, but lately I’ve been scribbling things in Gmail—I write lines in an unaddressed email, and that way I can come back to them later and transfer them to my computer. But sometimes I finish them in Gmail.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

Lately—for the past five years or so—I haven’t gotten writer’s block, exactly. What has happened instead is that I’ve gone through stretches during which I’ve been able to write but unable to write anything I like. This, it turns out, is far more terrifying than straightforward writer’s block—for me, at least. With writer’s block, there’s always the hope that once one is able to write again—if one is able to write again—one will be just as good at it as one was before. But during these stretches of greater-than-usual incapability, I fear I’ve lost whatever meagre skill I had, and I have no reason to think it will come back. After all, I can still write—I’m just bad at it. It’s harrowing. I have no tips for getting through it; I still feel shaken by the last time it happened.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless. I hardly ever listen to it these days, and haven’t really for 20 years, maybe, but it’s my favorite album of all time, and I honestly do think about it almost every day. I wouldn’t be who I am without it.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

Try not to use the construction “there is.” Lex Runciman, with whom I studied at Linfield College, taught me that. It sounds like a small thing, but it had an enormous impact on me. It was a way into thinking about what I wanted my writing to be.

How did you choose the personas that you inhabit in this book?

Yesterday, I was browsing in Unnameable Books, and I spotted a new biography of Vivian Meier. And instantly I knew I had to buy it, and I knew I had to write poems about Vivian Meier. I don’t know why, exactly. But it was much the same with the personas in In the Language of My Captor—I didn’t consciously choose to write about them so much as I felt like I couldn’t choose not write about them. I stumbled across each: Banjo Yes grew out of a conversation Melissa and I had about Stepin Fetchit, the speaker of the poems in the first section of the book was born when I happened to glance at the cover of a book about Ota Benga—almost instantly—and I first learned about Jim Limber on Twitter. In this way, discovering personas, for me, is much like writing poems: I have to be available for it to happen, and sometimes it does.

Do you set out to build certain forms and structures in your work or do they occur organically as you write?

A little of both, really. I tend to fall back on writing sonnets, and all the poems Jim Limber speaks in the book are sonnets, but with the first section I allowed the shape of each poem to be determined by its initial stanza—if that first stanza had, say, 17 feet, then every stanza after it would also have 17 feet. And the poems in the Banjo Yes section, while still iambic, were for the most part structurally free.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.