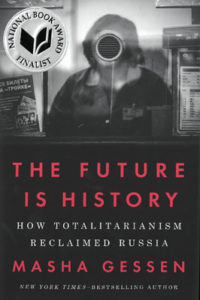

Meet National Book Award Finalist Masha Gessen

The Author of The Future Is History on how to make every story interesting

The 2017 National Book Awards (also known as the Oscars of the literary world), will be held on November 15th in New York City. In preparation for the ceremony, and to celebrate all of the wonderful books and authors nominated for the awards this year, Literary Hub will be sharing short interviews with each of the finalists in all four categories: Young People’s Literature, Poetry, Nonfiction, and Fiction.

Masha Gessen’s The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia (Riverhead Books / Penguin Random House) is a finalist for the 2017 National Book Award in Nonfiction. The book tells the complicated history of modern Russia through the stories of seven of its citizens. Literary Hub asked Masha a few questions about her book, her life as a writer, and the state of the world.

What time of day do you write (and why)?

I write from 11 pm until 4 am. That is a time free of distraction (I am so old that my habits date back to a time when ringing phones were a concern), meaning free of excuses for not writing. For the same reasons, I write well on planes.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

Deadlines. Fear of missing a deadline, that is, does wonders for overcoming writer’s block. Though, to be honest, I’ve never experienced the state that I have heard other people describe as writer’s block.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

I can read anything by Hannah Arendt to kick my brain into overdrive. So sometimes, when I am about to leave the house, I will stick one of her books into my bag—or The Portable Hannah Arendt, if I’m not sure which one I’m in the mood for. An entirely different go-to book is Love, Death and the Changing of the Seasons by Marilyn Hacker.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

The film Cabaret.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

When I was in my early 20s, I worked as an editor at The Advocate, which was once, briefly, a great gay magazine. The editor who made it great, Richard Rouilard, once came into my office with a story I’d assigned and edited—he’d taken it off the wall. It was about Tom Duane, who was then mounting a campaign for the New York City Council, I think. It mentioned that he was HIV-positive and went on to talk about other stuff. This was 1991 or ’92—people didn’t perceive HIV infection as a manageable illness—and Richard talked to me about how all anyone who read the story wanted to know was what Duane thought about running for office while sick, how he saw his future and his responsibility, how he managed his illness, all these human-curiosity questions that the story politely skirted. That made the story boring. I think back to that conversation a lot, and try to make every story I tell interesting.

Everyone always asks you this, but: what can Americans learn from how Russians have dealt with the onset of totalitarianism?

That’s easy: Don’t be like the Russians. Don’t cooperate. Don’t retreat. Don’t passively hope for the best. Above all, don’t assume that the worst won’t happen.

Will Putin last forever? When and how can we expect things to change in Moscow?

Nothing lasts forever, so Putin won’t. But he has created a closed system that is virtually impervious to outside pressure. It will collapse from the inside, likely, though not necessarily, when Putin dies. After that, things will be in disarray. Putin plans to live forever, so there will be no succession plan. There will be a scramble (for some detail on what it might look like, I recommend Joshua Rubenstein’s terrific book Last Days of Stalin). I think that the borders of Russia will be redrawn—it’s a tense and complicated federation now, held together by pressure, fear, and habit. But I don’t hold out a lot of hope, because I think that damage that’s been done to that society is just unspeakable.

Could Putin’s rise have happened in any other country? Every other country?

Sure, and I think this is important: mediocre men become leaders of nations by accident. This happens—it’s not an exceptional event. And if these mediocre men have a talent for trafficking in fear and nostalgia, they get to hold on to power. Now, I think that the particulars of what has happened to Russia have a lot to do with what happened to Russia before Putin: I think he set out to build a mafia regime but ended tapping into a reservoir of totalitarian customs and institutions. In a different country, he would have done a different kind of damage.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.