Meet National Book Award Finalist David Grann

The author of Killers of the Flower Moon on Joan Didion and the devil

The 2017 National Book Awards (also known as the Oscars of the literary world), will be held on November 15th in New York City. In preparation for the ceremony, and to celebrate all of the wonderful books and authors nominated for the awards this year, Literary Hub will be sharing short interviews with each of the finalists in all four categories: Young People’s Literature, Poetry, Nonfiction, and Fiction.

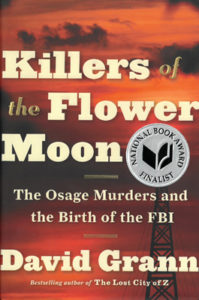

David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI (Doubleday / Penguin Random House) is a finalist for the 2017 National Book Award in Nonfiction. The book takes us to 1920s Oklahoma to tell the story of the mysterious series of murders of members of the Osage Indian nation, and the massive conspiracy that simmered just below the surface of these heinous crimes. Literary Hub asked David a few questions about his book, his process, and his life as a writer.

What’s the best book you’ve read this year?

Well, it’s not a new book, but I recently read for the first time Richard Rhodes’s The Making of the Atomic Bomb. Originally published in 1986, it is a reminder of how history should be written and told.

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

The person who I tell everything first—my wife, Kyra.

What time of day do you write (and why)?

I usually begin working at nine in the morning, and I have a goal of writing five hundred words a day. On some blessed days, I will be done by five in the afternoon. Alas, there are other days when I’ll be at my desk until one in the morning.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

At first, I stare at the blank computer screen. Then, when that fails, I do the crossword puzzle, search Trump’s latest tweets, read the newspaper, and randomly dial friends—until hopefully the spell breaks.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

I find myself constantly revisiting Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem, partly because of her luminescent prose and partly because she is so acute at rendering the unravelling of American society—which seems particularly relevant today.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

TV crime shows—I’m a shamefully compulsive watcher.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

If you want to be a writer, then write.

How did you first become interested in writing about the Osage murders?

The book grew out of a visit I made the Osage Nation Museum, in Oklahoma, several years ago. When I was there, I came across a photograph on the wall, which was taken in 1914 and showed a seemingly innocent gathering of white settlers and members of the Osage Nation. But part of the picture had been cut out. When I asked the museum director why, she said that it contained the image of a figure so frightening that she had removed it. She then pointed to the missing panel and said, “The devil was standing right there.”

The figure was one of the white settlers who had participated in the systematic killing of the Osage for their oil money. The Osage had removed the image not to forget what had happened, but because they can’t forget. And yet so many others, including myself, had no knowledge of one of the most sinister crimes and egregious racial injustices in American history.

How did your project change, if it did, from the initial idea to the finished book?

Initially, I had thought of the book as a traditional crime story, which was about who did it. But the more research I did, the more I realized that this was really a story about who didn’t do it. There was a culture of killing, in which so many white people—including bankers and businessmen and lawmen and politicians—were complicit in murdering the Osage for their oil money. The finished book became a dismantling of the original conception.