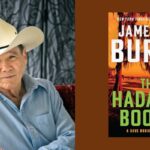

Meet National Book Award Finalist Danez Smith

The author of Don't Call Us Dead on editing, performance, and instinct

The 2017 National Book Awards (also known as the Oscars of the literary world), will be held on November 15th in New York City. In preparation for the ceremony, and to celebrate all of the wonderful books and authors nominated for the awards this year, Literary Hub will be sharing short interviews with each of the finalists in all four categories: Young People’s Literature, Poetry, Nonfiction, and Fiction.

Danez Smith’s Don’t Call Us Dead: Poems (Graywolf Press) is a finalist for the 2017 National Book Award in Poetry. This collection is a powerful book about blackness and queerness and sickness and death, and life in an America so often blind or indifferent—or hostile—to these qualities. It’s often harrowing, but there’s joy in there too, and a formal inventiveness that makes even the words shown flat on the page feel like an ecstatic performance. Literary Hub asked Danez a few questions about their book, life as a poet, and how it feels to be a finalist.

What’s the best book you read this year?

Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas. It was one of those books that made me start over the moment I finished it cause the book wasn’t finished with me. While I am super excited to see my book on this finalist list, seeing Layli’s brilliant collection made it jump a few inches higher.

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

I called my mom right away. I always call my mom when good news comes to me, bad news too. I don’t think there is any love in my life that compares to my mother’s love, and because of that her joy is the one that most feeds me, that feels the most like home.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I don’t believe in writer’s block. When I am experiencing what feels like it, I know I need to do one of a few things. The first would be to stop writing and to focus on absorbing art. When I’m not happy with my writing, I know I need to spend more time listening, looking, reading, touching, & tasting other people’s creativity to feed my own. The other thing I have to do is ask questions. (Why am I stuck? Is it the piece? Am I feeling balanced enough in other areas in my life to flouring in my writing? Am I hungry? Am I tired? Are the idea and the genre of what I’m working on agreeing with each other? Am I experiencing a road block or a directive to try something else?) Another option is to write through it, to write every ugly, horrible sentence that comes to mind and just work until I find something of value. I am a firm believer that every bit of writing is a necessary part of the process, and I’ve come to trust that on the other side of the “block” is something new and exciting waiting for me.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

If I should ever wake up in a world without Black girls singing their asses off, I’d have no more use for the world. The world of singers like Jamila Woods, K. Raydio, SZA, Kelela, Her, Rihanna, and groups like KING keep my soul sustained. There voices are the landscapes I lock myself in when I’m writing and thinking about writing. I am indebted to their genius for lighting my spirit up.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

“If your poems are only good when you’re around to read them, are they any good?”—Amaud Johnson

That blew my little 20 year-old, slam poet mind. And I haven’t been the same since. I’ve come to add this little tidbit when I pass it on to my students, “. . .and if your poem is ruined when you read it out loud, is it any good? How do you make sure your poem is alive both on the page and in the air?”

Some of the poems in this book have impressive and unusual structural elements—how much of the form is a natural instinct and how much is learned or constructed?

I’m not sure. I think, with form, the point is to learn, apply, and play until it feels like instinct. I don’t see these as mutually exclusive. I construct my poems in ways that feel natural, but who is to say what is learned/absorbed and what is learned? Poems themselves are a learned thing. I didn’t instinctually start writing poems, I was introduced to the genre and studied it and loved it and kept at it and continue to learn from it. Maybe what I’m saying is . . . I don’t know what is what. When I’m writing, I don’t know what is “instinct” and what is “training”, my concern is what feels right and what best serves the poem.

I’ve heard you revise poems even after they’ve been published. How do you know when a poem is finished? Is a poem ever finished?

Editing can go on forever if you let it, so I guess no piece of writing is ever “finished.” I stop working on a poem when it tells me it’s done. I know that sounds very art-bullshity but it’s true. I think, maybe, what that means is finding the place where the poem is closest to what I want to say and what I want the reader to know. I don’t think I ever get it perfect, but the hope is to get right close to it.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.