Meet Elinor Glyn, “Shocker of Grandmothers” and Founder of the Modern Sex Novel

On the Author of the Most Widely Denounced Novel Published Before World War I

My new book is an unconventional biography about an unconventional British woman, the late Victorian romance writer and celebrity author Elinor Glyn (1864–1943) who midwifed much of the sexual ethos of Anglo-American popular culture. When she died peacefully in London, Glyn’s obituaries called her “the founder of the modern sex novel” and “originator of the popular term ‘It.’” They also recalled that the redheaded writer with cat-green eyes who had “shocked the world of our grandmothers” had “led a life as glamorous as anything in her novels,” earning the friendship and respect of the most powerful and creative personalities in Britain, France, and America, through war and peace, over the half century between 1890 and 1940.

Elinor Glyn’s life and legacy gives the lie to some of the most enduring assumptions regarding the dynamics involved in the ascent of mass culture. Most believe that the stories and images that took flight in the imaginations of so many people more than a century ago were man-made. Perhaps there is a vague awareness that women readers—long the primary consumers of fiction—and writers like Jane Austen were central from the start to the fortunes of the novel in Anglo-America (arguably its first mass culture). But that is all.

Nowhere has this notion about the assumed maleness of the movers and shakers who created our cultural past been more pervasive—or wrong—than in what has been called the basic story about the founding of Hollywood. This story focuses either on the creative genius of directors D.W. Griffith, Cecil B. DeMille, and Mack Sennett, or the business smarts of the mostly immigrant Jewish men who built the Hollywood studio system. As is often the case, the victor writes the history, and in the evolution of how power and prestige got distributed in the American film industry white men obviously won out.

But the reality of Hollywood’s founding, as much recent work has shown, was far more complicated given that it was the least sex-segregated of America’s major industries when Elinor Glyn arrived in Los Angeles in 1920. This startlingly unfamiliar landscape, in which many white women wielded considerable control, in part accounts for how Glyn managed “the paradox of bringing not only ‘good taste’ to the [movie] colony, but also ‘sex appeal,’” as both Sir Cecil Beaton—perhaps the twentieth century’s sharpest eye—and producer Samuel Goldwyn recognized.

Yet the durable belief that a masculine cast of characters established the dreamscapes of mass culture has consigned the influence of women like Elinor Glyn—who wrote of some of the most popular novels of her day, reoriented the romance genre, and set the mold for a new kind of female celebrity author and how to represent heterosexual sex in Hollywood—to the status of trash.

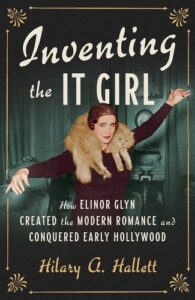

To be clear: this biographer has no interest in engaging debates about the relative artistic merits of Glyn’s many creative works. Rather, Inventing the It Girl restores the impossibly elegant, witty tastemaker and prolific author—of more than forty books, countless magazine articles, and 27 stories that became films—to her rightful place at the fountainhead of mass culture. For it was there that this visionary lady with hedonistic leanings infused her fantasies and philosophies about sex, love, and marriage into the romantic aesthetic that shaped the desires of untold millions of her fans for generations to come.

Elinor Glyn’s story begins in the privacy of her stepfather’s library, where, like so many women who became writers in her day, she had unfettered access to the materials she would draw on to fashion her own ideas about how life and love should work. But her story gathers steam at the point where most romances have always ended: after her marriage up the social ladder in 1892 to Clayton Glyn, a member of the English gentry class who was far less well off than he appeared. The marriage proved a misalliance and she soon turned to her pen for escape and, later, the economic survival of her family, which included her two little girls, Margot and Juliet.

Elinor Glyn’s story begins in the privacy of her stepfather’s library, where, like so many women who became writers in her day, she had unfettered access to the materials she would draw on to fashion her own ideas about how life and love should work.

Here is the place—in the aftermath of an adult woman’s reckoning with a difficult sexual and social adjustment to marriage—where Glyn would leave her mark as a writer. By 1901, she had become society’s premiere chronicler before devising, at the age of 43, the erotically focused modern romance novel with her great success-de-scandal, Three Weeks (1907). The novel celebrated the titularly short, illicit affair of an older, unhappily married Slavic queen and the patrician young lover she selects and schools in erotic arts to conceive their love child.

Perhaps the most widely denounced work of popular fiction published before World War I, Glyn’s “free love” novel helped to splinter the genteel code in English literature years before D.H. Lawrence’s more celebrated troubles with the censors. Three Weeks also reportedly sold more than 2 million copies in English by 1917, when republication in a cheaper “million-seller” edition produced an estimated 5 million copies. Translated into every major European language, it spawned a host of imitators, generating at least twelve adaptations in print and on stage, film, and television through 1977.

By the 1920s, “if a director wanted to show that one of the characters in his film was leading a racy life, all he had to do was show her holding a copy of Three Weeks in her lap, just holding the book was enough to tag her as independent and modern,” a silent-era film archivist observed decades later, explaining why Ohio censored a Disney cartoon in 1930 for showing Clarabelle the cow in a field reading Glyn’s bad book.

Although ostracized by much of British society, the popularity of her pro-sex tale purchased her a freedom of expression that the censors and the critics could not silence. Glyn rode her notoriety to unparalleled celebrity for a female author and, in the aftermath of her sudden rise to international fame, concocted a glamorous literary persona who blended her imposing stature as a very fashionable British lady with the seductiveness of her Tiger Queen heroine (so-called for the novel’s most infamous sex-scene on a tiger skin). This persona smoothed the acceptance of her naughty book.

The fame Glyn accumulated first as a novelist, and then as a journalist in Paris writing on modern morals and the state of society during World War I, led to her remarkable third act. Movie producers invited her to Hollywood in 1920 at the age of 56. In Los Angeles, she quickly established her leadership over the movie colony’s young residents and taught Hollywood’s first stars and directors how to express passion on the screen with a persuasiveness and finesse that delighted audiences and quieted the howls of the moral reformers during the Jazz Age. Glyn baked her approach to staging heterosexual sex into the visual style of mass culture. Rose petals, silken lingerie, long velvet gowns, and ropes of pearls have never gone out of fashion for signaling a woman’s sexual self-possession. Smoldering looks, long kisses, lingering caresses, and embraces that contain a show of force became the stock-in-trade of the romance, whatever medium. She conceived all of these.

For it is no exaggeration to say that all modern romance falls under the shadow cast by her chic silhouette. Elinor Glyn’s reorientation of the romance novel toward the “sex novel” focused on the essential, and often difficult, role that sexual passion played in love. This added the special ingredient that led the genre to outsell all others over the twentieth century (alongside detective stories).

If many don’t know that today, Glyn’s successors did.

Widely honored as the premiere poet of the Jazz Age and the flapper, Fitzgerald’s views on the period have been hailed as literary masterpieces and, all too often, taken to stand in for the whole. Relegated to the trash bin, the impress of Madame Glyn’s much more successful romantic effusions—in terms of absolute numbers reached—have left only the faintest recognition of her authorship behind.

Interestingly, Fitzgerald recognized Glyn’s position in the vanguard of projecting franker ideas about heterosexual passion—and particularly about the sexual desires of white women, which Fitzgerald himself seemed to fear and certainly never imagined from the inside out. A very young man in the 1920s, he mistakenly called Glyn, thirty-two years his senior, a contemporary. Fitzgerald was right because Elinor Glyn was, if nothing else, ever-forward looking, a woman ahead of her times.

______________________________

Excerpted from Inventing the It Girl: How Elinor Glyn Created the Modern Romance and Conquered Early Hollywood. Copyright © 2022 by Hilary A. Hallett. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Hilary A. Hallett

Hilary A. Hallett is the Mendelson Family Professor and director of American studies and associate professor of history at Columbia University. The author of Go West, Young Women! The Rise of Early Hollywood, she has written for the Los Angeles Times. Her book Inventing the It Girl: How Elinor Glyn Created the Modern Romance and Conquered Early Hollywood is available now.