The whole art of Kafka consists in forcing the reader to reread.

–Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus

I.

I was driving down Sunset for almost a mile or more before I realized I was driving down Sunset when sometime around the same time I realized I wasn’t supposed to be driving down Sunset but driving up Sunset, so after another mile of mostly staring down Sunset for somewhere to make a U turn, until I realized the hangover may have been hiding under the leftover high from last night while I wondered why the hell Sunset Boulevard wasn’t called Sunrise Boulevard in the morning, I turned left onto a side street then left again and again then turned right off of another side street to start driving up Sunset, though even with the sun in my eyes it didn’t feel like Sunday morning then as much as I felt like I was still stuck in mourning the night before while I tried to remember where it was I fell between the life and the death of the party.

East through Westwood toward West Hollywood where I would end up as far west as one can in West Hollywood before one isn’t, but where, after another U turn on Sunset, I picked up Adam outside of the drive-in where we were supposed to meet up at ten after ten if we weren’t both late. I wondered why it was still called a drive-in when one either had to valet or try for parking down some side street off Sunset to go to the drive-in, the drive-in that 50 years ago was a drive-in and now only a diner and drive-in only in name. It was still the diner I would have been sitting in with a cup of coffee if I were a handful of minutes earlier and with the same name of the drive-in I would have been dining in and still in the car if I were 50 years earlier, when the drive-in was more than a name held together, as if suspended somewhere in the space between a and the, with a proper noun and an s apostrophied between it and its drive-in like some possessive God.

I started down Sunset again, this time with Adam directing me west as if for the first time, but I didn’t really hear him until we were stopped at a red light and he said, like he was reading it off of something, Iranian New Year. The light turned colors and we started again and I stared up and saw all the signs stretched along toward the tops of the streetlights, offering as much shade as the palm trees they alternated with on either side of the street. The signs, the words in white contrasting with their backdrop colored in shades of green and softened reds covered in birds but flowery for bees, looked like all the other promotional signs the city always had postered up on the streetlights for cultural performances and the sorts of openings set in where the art was as much inside the architecture as it was itself the architecture, the closest one could ever come to the turning of seasons in this city being indoors and manmade and in museums.

Adam told me to turn left whenever I could turn left.

I told Adam whatever I remembered about the Iranian New Year going back to the beginning of time to Zoroastrianism, the vernal equinox with the day being half night and half day and the name of the new year more or less translating to New Day. I stared at another sign, reading about their celebration planned toward the middle of the month of March for the calendar year turning over to 1397, still in the dark as to why the Gregorian calendar had its New Year in the dead of winter, when there was rebirth right there in the death of winter. I knew the signs for the Iranian New Year weren’t there for me though, as much as they were there for the transplants, Iranian or not, the transplants there for everything else there were signs for in this city, since even the palm trees themselves were once transplants. I had stopped seeing the signs, the same as I had stopped staring up at the palm trees because in my eyes they had always been there, but then, without the sun in my eyes, or even with it, staring at the signs to see them again, all I saw is our sights seem to always be set somewhere in between seeing things that are not there and not seeing things that have always been there.

Adam told me we were there.

We stopped somewhere south of Sunset to go get coffee in a shop mostly made up of mothers with their children either falling in and out of sleep in their strollers or slinged to their chests, the coffeeshop having gotten enough stars to make up for an apparent absence of those other sorts of stars. Adam was telling me something about cryptocurrency, which I was happy to hear they had finally figured how to make money they can take with them when they die, as I was trying to sort the meter and wondered when all the quarters had changed or if I had lost my head to all the tails there were for each state. America seemed to always be so optimistic about itself in its states, but once all their tails started to come in, the odds of one out of fifty or fifty to one, out of many they were none. I didn’t have enough change until I saw the sign that read I didn’t even have to fill the meter on Sunday, so I thanked God.

We ordered pour-overs to go and Adam made use of the toilet while I drank several glasses of water in the time he took before the pour overs were poured and we were driving west again then south toward Venice. I had told him last night I would drive him in the morning to pick up a hard drive that had the second half of the film Adam and Santa Ana were still working on, for the time being called Out of Sight, Out of Mind, though they were happy to rename it if it was accepted by any of the film festivals like Cannes or Sundance they were submitting to, if they met their deadlines, which was why they were rushing to finish with the ADR and adding in subtitles for scenes they had shot in Mexico, which was why we were going to go pick up the second half of the film from the film editor Adam was paying more per week than I had made in all of last year. I realized I had ordered the coffee from Mexico because it was from Mexico and because it was good in the paper cup it came in to go, the sign for the shop on its side and again in black on brown on its sleeve, drinking the coffee whenever we were stopped and whenever there wasn’t traffic, finishing the coffee before we even got to Venice.

Adam told me he would be right back.

We picked up the hard drive and we drove to the ocean, though the closer we got to the water, the worse the traffic was, but it was still a sunny enough day to roll down the windows and wonder if I could afford a pair of prescription sunglasses as Adam went on about cryptocurrency and I thought about death in time. I stared at the speedometer on zero then the two types of measurements for distance over time in the three quarters of a circle, how we have the different measurements for the same distances, the only one we all give-or-take agree on being time.

The only difference I can see between the flag of the United States of America and the Confederate flag is a score and seventeen stars and some stripes.We stopped close enough to the water that there was sand where we parked off of the Venice Beach Boardwalk and walked to some restaurant that wouldn’t have even been there if it weren’t so close to the beach. Adam ordered a grilled chicken sandwich and I ordered huevos rancheros, asking for a cup of coffee too, which came first, the cup in a plate with three packets of creamer, before the coffee. The coffee was the sort of coffee that tastes better in a styrofoam cup or something else nondescript enough to not make one wonder about it ending up in the plastic Texas in the middle of the ocean, but there is nothing better than bad coffee. I waited to drink it as I stared at the beach then stared at the others in the restaurant and how much easier it is to sober up when one is still drunk, but still, being hungover is as close as one can come to being born.

Ten after ten seemed like such a strange time to meet somewhere, but ten and eleven were the two hours I always thought didn’t belong in the morning as much as they do at night. To see double so early in the day didn’t make as much sense to me as going straight from nine to noon with the sun snapping to attention overhead and my shadow beneath me like I was suddenly sitting up straight after a whole morning of poor posturing. Maybe it was because I was always done working on writing by ten and all I was doing then was trying to answer Adam on what I was working on, thinking I would try to take three days off from writing and the third novel I was working on then, knowing even before I took one off I would only take at most two.

Adam said something to try to sound like something I would write down, but all I could think was how every time I say last time was the last time, it’s only the last time since the last time. He told me his flight out was the morning after tomorrow and I could tell, being back in the city we were from, home never really meant as much when there was nowhere but home. Adam said his mother had sold the house last year and she already moved to one of those states in the American Southwest with its own timezone that doesn’t observe daylight saving time. I didn’t tell Adam my father wants to sell the house to move to somewhere in the South, because of the South being the South and most everyone I tell wondering why he would want to move to the South, but the only difference I can see between the flag of the United States of America and the Confederate flag is a score and seventeen stars and some stripes. Whether I told him or not, even before my birthday this year, the house I grew up in will be where someone else will grow up too. We spend enough time in a space and the space turns to time.

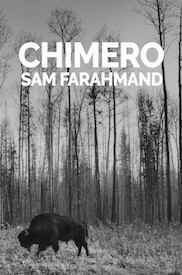

I realized none of this would have happened if I were writing then or either of us were on time to make it to the drive-in at ten after ten, but maybe I was thinking it over too much like trying to figure what came first between space and time. I couldn’t remember the day I started to go along with the Spiritus Mundane, waking up every day only to wake up again day after day, so I would take another break from drinking then spend almost all of the following week going up and down the mountains between the valley and the beach. I would end up looking for a higher high, hiking up to the top of a mountain with a sign that read the name of where I was, which could have even been translated to Golgotha, as much as anything can be translated to mean something more than it is. I would stare out at the ocean from the top of the mountain and even though I couldn’t see it with my eyes, I saw everything there was turning and turning in the widening North Pacific Gyre in the middle of the ocean somewhere in Plastic, Texas. I saw the third novel in there somewhere too with a white cover with only my name on the front, as in, Sam Farahmand.

U.

Something I have been wondering a lot about as of late is how the difference between is and was is two vowels, an a and an i, and one consonant named after a vowel twice, double-u. Something else I have been wondering a lot about as of late, though it’s sort of the same, is how the similarities between is and was are in their s‘s, but then again, consonants are the only constants in life.

It is something like life and death with their fricative ends, f and th, life with the teeth on the lip and death always ending on the tip of the tongue but both of them lingering at the ends of our mouths. There is so much going on in the mouth between the tongue and the teeth, it reminds me of all the th‘s in the King James Version of Ecclesiastes 1:3-5:

What profit hath a man of all his labour which he taketh under the sun. One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever. The sun also ariseth, and the sun goeth down, and hasteth to his place where he arose.

Literature was always something of a tracheotomy. Somewhere between breathing without either your nose or mouth and throat singing. Trying to write said literature, on the other hand, is somewhere between praying in tongues and speaking in a language one half-understands. Meaningless in some sense, but saying something is meaningless is about as meaningless as the words used to say something is meaningless. Not unlike wondering what came first between the egg and egg.

The sounds of the words, like the words themselves, must have taken longer to get to the sight of what the words were for, sound and sight being constants in their speed when traversing space through time, but space and time were always less an x and y than they are double-u, as in, space-time. The words, in taking their time traveling through space, remind me of the woods in this city of Westwoods and West Hollywoods, the way they are pronounced by transplanted Iranians, their w‘s, which maybe aren’t pronounced as hard in Farsi, always sounding like v‘s. The west will play closer to the vest as a was becomes a vase and, like those vases like faces, the difference is in the space between the pronunciations of vase and vase. I wonder if it all has to do with how difficult it is to hold onto the sound of a w between one’s lips when one can mouth a v with one’s teeth on one’s lips forever, vibrating a w to sound like half of what it once was, but w always was the ultraviolet of the letters of the alphabet in being both the beginning and the end of itself.

I worry my father and I are starting to lose our minds at the same time, which is good to have something in common.Maybe it isn’t a semiotics as much as it is a semisemiotics. Maybe it doesn’t affect me because writing is written with a silent double-u, but still, it does affect me when I will say I worry I can’t write like I used to write. Maybe there are too many words for not having the words. Maybe not.

I still see the silent double-u like white noise even if I know the fear of not having it is half of having it and I know holiness is in being half what it is and half what it’s not. The only difference between good and bad is time. A mispronunciation is the difference between good and God. It is like the two g sounds in Farsi, one a g and one a gh, which is an even harder g and more guttural like clearing your throat with a g as hard to pronounce for white people as it still seems to be for white people to find the g spot, but the difference between the g and the gh sounds is profound in words like gand and ghand, one used for a cube of sugar and one used for the smell of shit.

I write most of this essay between the Iranian New Year and Easter Sunday when I end up in the graveyard down the street from one of the oldest churches in America, where the president and all the president’s men worshipped their God even before he was president and even before, as one of the signs outside of the church read, their nation was all under God. I walk toward the church as the service ends and I see children with baskets full of plastic eggs, which look like they are supposed to be dyed, while all the other children of God are still waiting in line for their flesh and blood. I know the blood is blood, but I never could buy into the Sunday morning cannibalism and their controlled transubstantiation. There but for the grave of God go I.

I know I’m last in line for throwing stones, though I’m worried there won’t even be any stones let alone sins left for me when it is my turn to throw, but death never seemed to me as much of a problem for the dead as the living. The ones still in line look like they would pronounce the thus in Zarathustra a little too hard, but God isn’t as good as he is glottal, though for all the used gods there are to worship, they still have nothing on the sun. The ones in line who have done America to death, I stare at them to wonder if it’s not cannibalism if he no longer is a man, but then again, man is nothing more than the word man, even if the name on the church is Christ Church.

I will worry I can’t write like I used to write while I am on a flight back to Los Angeles for the last time with a childhood home to come home to, when I realize I am old enough to be my father. My father is 72 years old to the 27 I am and around the same age my father was when he was my half-sisters’ father, but I’m not even done being a son, though I will still wonder which one of us will be the first to go, since the gods don’t always even out the odds. I worry my father and I are starting to lose our minds at the same time, which is good to have something in common, though soon enough we will have nothing in common, but all’s well that ends. I will end up going to an Iranian bookstore in Westwood where all the transplanted Iranians are and where for the time being my mother tongue is dying in my mouth.

I reread the first essay I ever wrote, which was all about being an Iranian-American and about my father’s mother’s death in Iran and about time spent in a psychiatric ward and about neither of us having the words. I remember I went to a doctor for the first time since writing that first essay, because the last time I saw a doctor I wasn’t sure if I was the only one in the room who could see the doctor, but all this one said was I have a Vitamin D Deficiency. My father tells me maybe the Vitamin D deficiency is genetic, which I know but I don’t have the history of a heart condition to tell him everything in life is. As for the Vitamin D Deficiency, we all need our fifteen minutes in the sun, but I worry my identity for so long has been in trying to not have one, somewhere in between my words and my worst, I’m no longer so sure who I’m not.

I worry about writing this essay still because there are only so many lines one has in one life and I know I have been writing too many as of late and I wouldn’t know where to end if it weren’t for having that deadline that comes at the end, so I suppose I should thank God for that too. It is like the difference between moving the stone every day of one’s life and moving a stone the once when one comes back from the dead. I couldn’t count how many cups of coffee I had in writing this, but I drink enough coffee to realize coffee sounds like the Farsi for enough. Coffee is enough. Enough is enough. Coffee is enough of a difference between sugar and shit.

One week before I finish writing this essay I am told the first novel I wrote will be published, which makes me remember I once lost a first edition of The Sun Also Rises and the library wanted over a thousand dollars from me if I ever wanted to read again. One week after I finish writing this essay I go to the doctor to see if I can get a new prescription for sunglasses and I end up with my eyes dilated and, after some exam I have never seen before where half the screen is green and half is red, I am told I am not supposed to get the sun in my eyes for three to four hours. The day I finish writing this essay, my mother’s mother dies. I tell my mother I will take her to the beach, so she can get out of the house for some time, on the way there stopping to have an early brunch where the waitress looks like an actress and she says good morning because she doesn’t know my mother’s mother died. I order the egg sandwich and when we finish I tell the waitress she forgot to put one of the coffees on the check, but all she does is tell me I am a good person, so I have to believe everything happens for a season and once we get to the water I have one of the worst diarrheas I have ever had in a public toilet on the beach.

The words will always be there, whether I am or not, somewhere between my worries and my were’s. The words, like the difference between a and the, will always be there, and I know that is all there is and that that’s that. If I am only as good as my word, I am only as good as this line.

__________________________________

Chimero by Sam Farahmand is available via drDOCTOR.