Meaning in the Margins: On the Literary Value of Annotation

For As Long As There Have Been Printed Books, There Has Been Marginalia

“The vitality of language lies in its ability to limn the actual, imagined and possible lives of its speakers, readers, writers.”

–Toni Morrison, 1993 Nobel Lecture

*Article continues after advertisement

In 1993, Morrison was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for “novels characterized by visionary force and poetic import.” In her Nobel Lecture, she noted how language, whether spoken or written, can limn, or describe and detail, life. Derived from the Latin illuminare, meaning to “make light” or “illuminate,” limn has been used throughout literary history to generally describe—and convey the literal illustration of—a manuscript. One affordance of annotation is that it enables readers and writers to limn, or describe, their texts. In doing so, how does such annotation provide information?

The history of books and reading practices is an apt starting point. Annotation was both ubiquitous and habitual by the 1500s, not long after the invention of the printing press and growth of print culture. Throughout the early modern period, approximately 1500–1800, as scholar Heidi Brayman Hackel has recounted, book use among “less extraordinary readers”—or novices and everyday annotators—included people adding various types of marks while reading books. Marks of active reading, like underlining, indicated sustained engagement. Marks of ownership, such as signatures, distinguished books as valued objects. And marks of everyday recording, perhaps unrelated to the content, added ancillary information. In Brayman Hackel’s assessment, with varied annotation practices “the book takes on a different role: as intellectual process, as valued object, and as available paper.” Information, supplied by reader annotation, has for centuries helped books to take on these different roles.

By the 1600s, various markings among the early modern book routinely provided information by adding detail, indicating references (particularly to scripture and classical literature), emphasizing importance, translating or clarifying terminology, and organizing the text. It has even been suggested that some marks be considered “graffiti” indicating possession, presence (“I was here” notation), and defamation or praise. Medieval annotation also included drolleries, or small decorative images, drawn among the margins. What information might be gleaned from killer rabbits frolicking in the margins of medieval manuscripts?

The British Library, detailed record for Royal 10 E IV, f.61v

The British Library, detailed record for Royal 10 E IV, f.61v

As we consider what information annotation can provide, and how annotation can make information accessible and valuable, let’s return to our example of Morrison’s Beloved. Perhaps as a student you highlighted key passages of Beloved, jotted notes in the margins, or scribbled stars and question marks, all to better illustrate your growing literary knowledge. Perhaps your annotation of Beloved demonstrated burgeoning intellectual acumen or indicated how much you enjoyed the book, or maybe the book was simply some paper on which to record gossip. Your annotation would signal different information to different readers: insight, appreciation, or distraction. If passing your course was a goal, then notes of active reading may have better aided your future essay writing and study, or have indicated to your teacher that you completed an assignment. George Steiner, a literary critic, once suggested that an intellectual was “quite simply, a human being who has a pencil in his or her hand when reading a book.”

Annotation was both ubiquitous and habitual by the 1500s, not long after the invention of the printing press and growth of print culture.

Annotation can enable informative literary practices. But not always. A productive relationship between annotation and information must be neither arbitrary nor incidental. Seldom are chemistry formulas annotated within Beloved. Literary analysis is unlikely inside your grandmother’s cookbook. The 6,106 annotations comprising “Your Biking Wisdom in 10 Words,” a series of interactive maps curated by the New York Times, and annotated with advice and know-how, is most useful for cyclists in a given city who desire information from insightful riders about a relaxing route or safe commute.

Whether you annotated Beloved with a pencil in hand or typed your note using a digital interface, your annotation may be perceived as more or less informative given a number of considerations. First, private annotation may have been germane to your needs, but may not reflect the concerns of a peer or resonate with a broader public. Second, your novice interpretations may be irrelevant when read by an expert, just as a specialist’s note may require scaffolds to help you learn.

And third, your annotation, perhaps written years ago, may diminish in importance or comprehension over time. Annotation can enable access to new meaning and knowledge, though the information supplied by annotators should be opportune and beneficial. In other words, the resonance of information provided by annotation cannot be taken for granted and may very likely shift with the passage of time.

Annotation can furnish information—and annotation can be perceived by readers and other annotators as valuable—when notes added to texts are capable of being put to good use, exhibiting relevance, and addressing needs or curiosities. Annotation can limn texts when these “silent embers” illuminate knowledge that is useful, relevant, and timely.

*

Whether with manuscript annotation from the Elizabethan era or human-assisted annotation of big data, annotation is useful when authored and referenced in context. Let’s revisit the early modern period to better appreciate how information needs context. Now considered required reading for English majors, John Dryden’s 1681 poem Absalom and Achitophel is satire that relies on readers’ knowledge of seventeenth-century English politics like the Popish Plot as well as the biblical story of Absalom and King David. The poem’s title refers to an Old Testament story of a feud between King David and his son Absalom, connecting the biblical characters to King Charles II and his son James Scott.

A productive relationship between annotation and information must be neither arbitrary nor incidental.

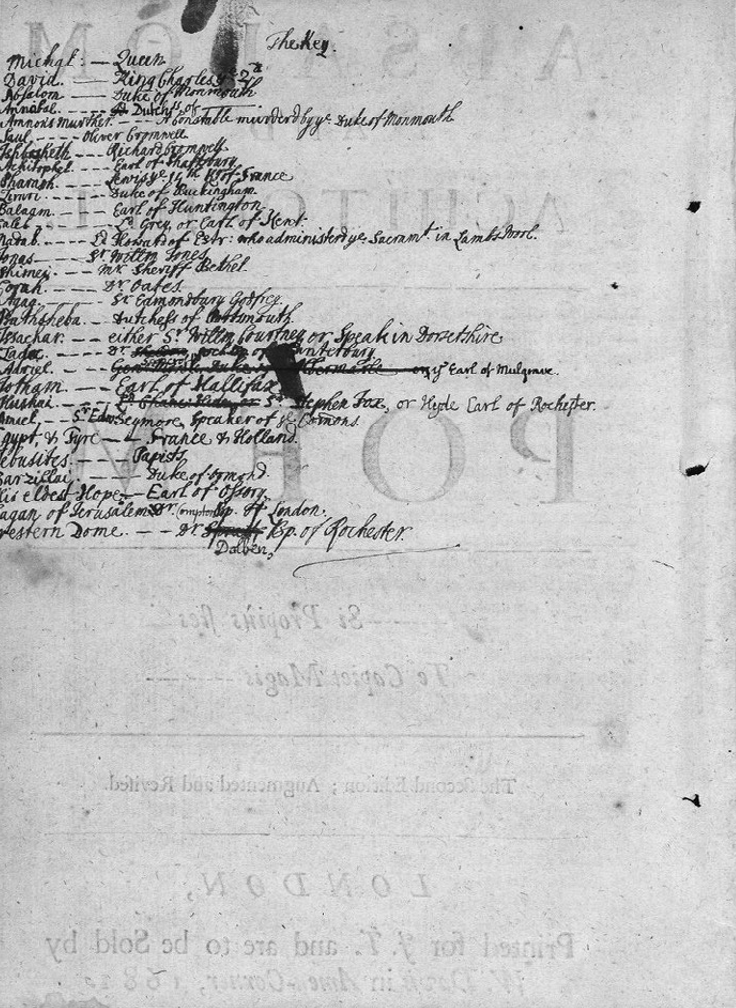

Were you to read Absalom and Achitophel almost 350 years after its publication, understanding the poem’s political and biblical context along with its satirical nature might require additional information. Today, readers of the poem frequently turn to footnotes, explanatory essays, and even primers in biblical literature before coming to terms with the poem’s content and meaning. Whether for scholars or students, such annotation is useful in adding information about the poem’s characters as Absalom and Achitophel is a veiled allegory about King Charles II. Present-day readers benefit from relevant annotation providing contextual information about Absalom and Achitophel. And so did Dryden’s contemporaries. Printed versions of the poem often featured an annotated “key” (figure 8), handwritten by the manuscript owner associating biblical characters with corresponding members of English royalty.

The keys added to Absalom and Achitophel demonstrate how annotation can assist with, in the words of English professor William Slights, “Transporting information across the borders of the printed page.”6 Both readers of the past and present require contextual and pertinent information to fully comprehend Absalom and Achitophel. This information also helps contextualize the poem’s purpose in a given period of time. When Dryden wrote the piece, it functioned as palace intrigue. Now the poem is regarded as quintessential satire and lauded for the use of heroic couplets.

William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California at Los Angeles.

William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California at Los Angeles.

Absalom and Achitophel is a useful example of how annotation supplies relevant information, and how that information needs context so that readers gain access to knowledge. As a poem with layered meaning and complex wordplay, Dryden’s work required—and still does—that experts present annotation for readers to make sense of overlapping historical, political, biblical, and aesthetic contexts. With Absalom and Achitophel regarded as a valued contribution to English literature, today’s readers rely on annotation as contextual information to understand the poem’s content and literary significance.

__________________________________

From Annotation by Remi H. Kalir and Antero Garcia. Used with the permission of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2021 by Remi H. Kalir and Antero Garcia.

Remi Kalir and Antero Garcia

Remi Kalir is Assistant Professor of Learning Design and Technology at the University of Colorado Denver School of Education and Human Development.

Antero Garcia is Assistant Professor of Education at Stanford University's Graduate School of Education. He is the author of Good Reception: Teens, Teachers, and Mobile Media in a Los Angeles High School (MIT Press).