Like most people, my first glimpse of the Fyre Festival was on Instagram. The slick commercial venture exploded onto America’s social media feeds in December of 2016, as hundreds of verified influencers—blue-check Instagram celebrities with tens of millions of combined followers—started posting the same ambiguous burnt sienna square, suggesting their fans #joinme by purchasing tickets to the mysterious event. The festival organizers who had hired the internet stars to promote the event were promising ticket buyers “two transformative weekends” of fabulous luxury on a private island formerly owned by Pablo Escobar, where they’d be flown in on private jets, pampered by a dedicated wellness team and nourished with meals designed by celebrity chef Stephen Starr.

A follow-up commercial—a medley of half-naked twenty-something models interspersed with stock footage of other music festivals—subsequently went viral, and Vogue immediately deemed it the “supermodel antidote to the winter blues,” recommending the festival as a way to “preemptively fix that Coachella FOMO.” (Vogue has since edited any references to Fyre from the piece, though it lives on in the URL.)

That was enough for me to know as a consumer that the event wasn’t for me, and as a journalist, I probably would have let the whole thing pass me by, had a guy I had gone to high school with not put together his own little Instagram commercial on his private account, flaunting his VIP Artist Pass wristbands and outlining, slide by slide, all the outrageous amenities guaranteed by the festival organizers.

Suddenly I felt anxious. Was I about to miss the party of a lifetime? I clicked the link to find out.

What I found there made no sense. The site was offering $250,000 ticket packages with yachts and private chefs, yet it looked like it had been designed in a high-school coding class. The text promised slick, intoxicating luxury beyond comprehension, but outside of a commercial shoot interspersed with obvious stock footage, there were no photos to back any of up. The headliner for this supposedly exclusive luxury event was Blink-182, a band that peaked when I was in elementary school, which I will just say generally was… quite a long time ago.

Now I was extremely interested, but not for the reasons Fyre Media CEO Billy McFarland and his cohorts were hoping. Quite simply, I smelled a scam. And I wasn’t the only one. At least two men—one with connections to the music industry, and one with connections to the Bahamas—had already taken the dramatic step of registering social media accounts and websites to anonymously warn consumers that this thing was never going to happen. It seemed so obvious something was terribly wrong.

The most incredible part of the whole thing was that no one was listening.

Even my editors at VICE News, focused as they were on international stories and war documentaries, were initially dismissive. “A music festival that was overhyped? Not sure that’s a VICE story,” one of them told me. I’ve joked that getting my initial story on the Fyre Festival published felt a lot like trying to convert to Judaism, but in the end it wasn’t that far off base: I had to pitch it three times before the editorial beit din saw the now-legendary cheese sandwich photos on social media and decided it was go time. And even then, they only allowed me to cover it in text, rejecting requests to send a VICE News Tonight camera crew to the island to capture the disaster in real time. (Luckily, between the Fyre organizers’ own cameras and the hundreds of tech-savvy millennials stranded in the gravel pit, there was plenty of footage to go around.)

I’ve often wondered if the breakdown was due to my failure to appropriately describe the story I had stumbled into, or if the adults in the room’s failure to recognize it reflected just how normalized pure, substantive-free hype had become. After all, Fyre’s influencer blitz had yielded immediate returns on social media, which triggered national press coverage, which gave the whole endeavor a patina of legitimacy.

Within hours of the Instagram onslaught, the Fyre Festival name was everywhere—on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter; on news websites; and even old-fashioned but still-coveted TV segments. Marketers involved in the campaign estimated 95 percent of the festival’s tickets were sold in that first week, even though, as the world later discovered, the festival they sold consumers never even came close to existing. As we all know now, that divide between Instagram and reality resulted in the Lord of the Flies-esque chaos seen ’round the world, as hundreds of well-heeled millennials were trapped in the Bahamas with not much more than a wet mattress and an Instagram Story to show for the thousands of dollars they’d invested in the experience.

But as I followed the story past the initial Bahamian disaster into Billy McFarland’s felony arrest, surprise felony rearrest, and federal sentencing, it became clear to me that there was something bigger at play: the natural end point of a society primed to trust their own emotions over objective, verifiable facts, in a world that tends to value the signifiers of success over actual achievements.

I saw it as I broke the story of the Fyre Festival implosion for VICE News, and it continued as I executive-produced the Emmy-nominated Netflix documentary Fyre: The Greatest Party That Never Happened. Along the way, I learned a whole lot about how scams are thriving in the age of social media—and how often we’ve collectively agreed as a society to treat hype as an indicator that we’re playing with the real deal.

These dynamics played out in a number of ways throughout my reporting on Fyre. At first I thought the story had reached its zenith when Billy McFarland, then 25 years old, was arrested in the summer of 2017 and charged with wire fraud not for pied pipering a bunch of desperate twenty-somethings to Paradise Lost, but for defrauding his investors about the state of Fyre Media. (He had claimed the company was generating millions of dollars in revenue, which it was not.)

As we all know now, that divide between Instagram and reality resulted in the Lord of the Flies–esque chaos seen ’round the world.

A bonus shock came a year later, long after he had pleaded guilty to the first set of charges. At the time, McFarland had been out on bail pending a sentencing hearing for the charges stemming from the Fyre Festival. Most, including the prosecutors and the class action attorney representing his victims, assumed he had spent that time hiding out in his parents’ basement in New Jersey. But I had heard a rumor he was actually back in the city, living large in a Midtown hotel penthouse and bragging about his crimes at nightclubs and upscale strip joints. In any event, he definitely wasn’t sitting at home thinking about what he had done wrong.

For weeks, I had been getting credible reports that Fyre Festival attendees were being targeted with emails from a new company called NYC VIP Access, which was offering ludicrously expensive tickets to exclusive celebrity events like the Met Gala, the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show, and Burning Man. That someone would be brokering these types of exclusive opportunities wasn’t totally implausible—high-price concierge services accounted for an estimated $297 million market in 2017—but something just felt off about these offers, in the same way the Fyre Festival website had felt off when I first clicked through.

I started investigating and found, rather quickly, that it just wasn’t possible to fulfill the experiences NYC VIP Access had been offering. For example, Met Gala tickets can’t be purchased, and anyone with a tenuous connection to the event who plans on trying to buy their way in anyway, like, say, an executive representing one of the brands who sponsor the Gala, has to first be personally approved by Anna Wintour.

When I called up an NYC VIP Access sales rep under the guise of an interested customer to ask about an offer for tickets to the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show, the man who answered the phone explained to me (in a rather condescending tone!) that the models confirmed to walk in the show had promised the company their allotted VIP seats. He went on to suggest he might deign to sell me a pair if I filled out and returned a credit card authorization form that same day. But that year’s show hadn’t even announced its location yet, and the annual casting, which famously guarantees no spot to any model—even if she walked the year before—was still months away.

A simple Google search revealed Burning Man had no corporate sponsors to provide NYC VIP with the tickets they assured me had been provided by corporate sponsors, and I was able to confirm that, despite NYC VIP’s backstage Reputation tour offers, Taylor Swift had stopped selling meet and greets some time ago, due to security concerns.

On June 12, 2018, having debunked almost all of NYC VIP’s offers, I published a final article in a series focused on the many connections between this shady new access company and Billy McFarland, who had repeatedly denied any involvement. About six hours after the piece went live, McFarland was rearrested and charged with a pair of felonies related to the ticket-selling scheme. According to the FBI, he had managed to pocket more than $100,000 by scamming his original victims while out on bail. In July, he again pleaded guilty and was sentenced that fall to six years total for both incidents—two counts of wire fraud stemming from the festival and two counts of wire fraud and money laundering related to the NYC VIP Access scam.

Still, the fact that he had turned around and committed two felonies while out on bail for two other felonies ultimately made little difference in his sentencing. In a bizarre turn, the judge actually challenged in open court one of McFarland’s psychologist’s conclusions that McFarland did not meet the criteria for a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder, and then turned around and granted him the relatively lenient sentence, to be served in a low-security white-collar prison. It wasn’t exactly a bad outcome on charges that could have landed him more than 75 years behind bars under the maximum sentencing guidelines before a judge who had just suggested he might be a psychopath.

But by then I had realized, while reporting on McFarland’s myriad scams, that the real meat wasn’t a recap of his crimes and how he did them but, rather, why they worked so well—and why so many people he had already duped once fell for it again just a few months later. Why were his victims, once burned, willing to take another chance on an offer that seemed way too good to be true? Why did experienced investors repeatedly give millions of dollars to a college dropout with no real product or sales record?

Why were his victims, once burned, willing to take another chance on an offer that seemed way too good to be true?

Why did serious professionals, with decades in their industries, who knew or should have known that the original festival wasn’t going to happen, keep working toward its inevitable implosion? Why was one of them willing to give a Bahamian official a (literal, not figurative) blow job just to ensure McFarland’s shipment of Evian water would make it on time—and still be open to visiting him in prison after? Why did thousands of the most image-conscious, web-savvy youths in America eagerly throw their money at an illusion? And why, long after it became clear something was seriously wrong with the event, did hundreds of those young people still jump on hastily chartered last-minute flights to a foreign country? Suddenly I was seeing patterns everywhere, like the John Nash of influencer marketing, with red yarn tying together Billy McFarland and Donald Trump, while Elon Musk and Kris Jenner faced off from opposite ends of my brain conspiracy board.

Con artists have presumably been around since prehistoric times. But there was something new here at play, a tech-assisted accelerant, that enabled McFarland to subvert our hyperconnected society, which, given all these technological advancements, should have spotlighted him from miles away. But by filtering his scam through a network of trusted influencers on social media, which caught the attention of legacy news outlets more than happy to cover things superficially from an entertainment angle, McFarland had been able to wash the stench of fraud from his scheme, resulting in a pure hype cycle that bypassed any need for proof of concept.

And with a millennial army willing to follow these influential generals from the screen to the literal ends of the earth, McFarland was able to convince a series of experienced investors to keep funding the scam—at least until it all fell apart in real time, where else, but on social media. McFarland may, for a time, have been the most famous, but he is not, by far, the only con artist feasting on hype in the digital age.

It’s tempting to chalk all this up to the naivete of young people. But it’s not just millennials and Gen Z’ers falling for it—it’s their parents too. This impetus to dive blindly into a shallow pool of unverified claims spans generational, socioeconomic, and educational levels, from the 28-year-old North Carolina man who shot up a pizza parlor because he falsely believed it was a front for child sex trafficking, all the way up to 97-year-old Henry Kissinger, who accepted a seat on the board of directors of Theranos, one of the biggest scam companies that ever existed. At least he just lost his dignity—the Walton family (which owns Walmart), Rupert Murdoch, and the DeVos family—all of them presumably sophisticated investors and certainly long-term professional rich people—reportedly lost a combined $375 million in Theranos.

It’s the same mindset that brought us Juicero, the $400 juicing machine that managed to raise 120 million real dollars before a journalist figured out the machine only worked almost as well as squeezing the bags of fruit pulp with your own two hands. It’s the millions of people tuning into Newsmax, a television channel that appears to exist solely to cater to people who feel Fox News committed a crime punishable by death for calling the state of Arizona for Joe Biden on Election Night.

In retrospect, it’s little wonder McFarland thought he could sell a half-brained idea and use someone else’s money to try to make it come true. Wishful thinking wrapped up into an aggressive sales pitch and pounded into the public psyche via pop culture and social media until enough people give up resisting the idea is just good business practice.

We have more tools available to uncover bad actors than ever before, yet we persist in playing along with them.The result is a curious conundrum of this connected age. We have more tools available to uncover bad actors than ever before, yet we persist in playing along with them. We keep arguing online with bots and ordering products on Amazon from companies that don’t exist (this happens far more often than you’d think) simply because they were favorably reviewed by someone we don’t know. An entirely new currency that doesn’t actually exist is thriving in the multibillion-dollar crypto exchange, enabling companies like Burger King Russia and Kodak to goose their stock prices just by announcing plans for their own branded version of fake digital money.

We’re taking vitamins we don’t need and swallowing supplements we can’t pronounce and putting jade eggs in our vaginas because we were told to do so by freelance writers whose only health qualifications are working for a site that happens to be owned by the beautiful and famous movie star Gwyneth Paltrow. Is any of it all that different from the thousands of kids who entrusted their physical safety to a 25-year-old scammer simply because the model Bella Hadid accepted north of $300,000 to wink at a camera?

Public Enemy’s “Don’t Believe the Hype” dropped in 1988. Thirty-some years later, it would seem we’ve learned nothing.

__________________________________

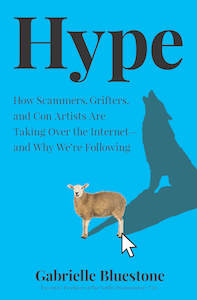

Excerpted from Hype: How Scammers, Grifters, and Con Artists Are Taking Over the Internet―and Why We’re Following. Used with the permission of the publisher, HarperCollins/Hanover Square Press. Copyright © 2021 by Gabrielle Bluestone.