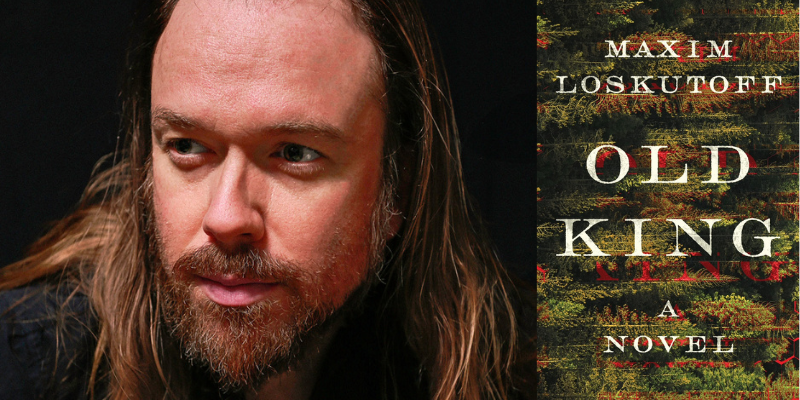

Maxim Loskutoff on the Unabomber and the Myth of the American West

In Conversation with V.V. Ganeshananthan and Matt Gallagher on Fiction/Non/Fiction

Novelist Maxim Loskutoff joins co-host V.V. Ganeshananthan and guest co-host Matt Gallagher to talk about his new novel, Old King, which is about Unabomber Ted Kaczynski, who moved to Montana to withdraw from society. Loskutoff, who grew up in Missoula, Montana, discusses the mythology that draws men like Kaczynski—who sought to be in nature, and to avoid technology and other people—to his home state; the gap between the imaginary American West and its reality; and how these connect to American settler colonialism. He also explains how he positioned the Kaczynski of his novel not as a hero or even an antihero, but as a symbol of this dark and unhealed facet of American society. Loskutoff reads from Old King.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

V.V. Ganeshananthan: [After Loskutoff reads from a section from Kaczynski’s point of view] Gosh, it is so intense to be in that mind. I wonder if you could just talk to us a little bit about the writerly project of entering that interiority, deciding to do that via fiction rather than nonfiction, you use his real name. I wonder if you could just talk a little bit about some of the early steps of the decision making or exploration that you did as you were starting the novel, and just thinking about how this story would align with known facts, because there’s a lot of references in there to things that actually happen, and then also, of course, some really juicy wandering into things that I’m not sure if they did or not.

Maxim Loskutoff: Well, to just finish my summary of Ted Kaczynski’s life and actions, once he came to Montana, he began from these acres that he bought outside of Lincoln. He first built himself this one room windowless shack, and then he set to work making bombs. And this was something he’d played with beginning when he was a teenager, making fireworks, but once he was in the Montana woods, he began creating bombs with the intention of killing people. And he would send these bombs through the mail or he would drop them off. He did both, but he became famous in the American imagination for the postal bombs that he sent to victims through the mail. And by the time he was captured 20 some years later, he had killed three people and injured 23 more.

And so the reason this book took me so long to write was struggling with those exact questions. I very much didn’t want Ted to become the hero of this book, or even the anti-hero, and I didn’t want the arc of the book to be a sense that, “Oh, he got his comeuppance, and now, you know, vengeance is served, and we can all move on.” Because what he always represented, to me, was something deeper and darker in the American society that we haven’t dealt with and we haven’t healed at this point, and that is the idea of the lone wolf, usually a man, but a person who is so upset about the way things are that they feel justified in going off and enacting violence against complete strangers, you know, completely innocent bystanders.

And so, the question of how to position him in the book was what I spent far and away the most time with, and I knew I didn’t want him to be a central character. You know, the way he has always felt to me as a Montanan is as a part of this dark shadow that hangs over the entire interior West in modern America. And so, what I eventually settled on was that the main character of this story is the community itself and the natural setting, this valley, and Ted is very much a shadow over this community, you know? And through the years of research and reading his journals and reading accounts of his neighbors, what became clear is that his acts of cruelty extended far beyond the bombs he sent. He killed at least six of his neighbor’s dogs over the years in a very slow and secretive way. He would write in his journal about fantasizing about killing his neighbor’s daughter, really anything that made noise that disturbed him. He hated the dirt bikers that would use the old logging roads around his cabin, and he would sometimes string razor wires across paths hoping to badly injure one of them.

And so, really, my way into the book was to focus on the community itself, and to fictionalize the characters around him, but I wanted to be very sure to not have the character of Ted Kaczynski, since I was using his real name and his real story, do anything terrible that he didn’t actually do in real life. So the acts of sabotage and kind of petty cruelty that are in the book, that were not in the news stories are, in fact, things that I found in my research. And then it was a matter of building this world around him to show both the damage he was doing on a small level and the much larger damage that was happening in America at large during this time.

V.V.G.: Wow. I mean, yeah, the smaller acts of cruelty are so telling. And it seems like, also, there’s such a volume of information about him that, I mean, how did you know when to stop yourself? It seems like you could just really, you could plunge into that ocean and never come out.

ML: Absolutely. And I think that the other characters in the book really became the counterbalance because, on a deeper level, what I was trying to write about is, what is this urge that brings wave after wave of people in this culture to places that they consider the frontier, whether the people who are already living there consider them that way anymore, has never been relevant. You know, since the first settlers, there’s been this urge to go to the frontier and remake it in your own image, you know, no matter what the people who are already there are doing, or what the landscape or the animals or this entire pre-existing world that’s there. And so, the book ended up being about, you know, three very different men who come with that same desire, you know? Ted comes with this incredibly dark urge. He wants to go to the frontier so that he can launch his attacks on society at large.

Another one of the characters, who’s a forest ranger from the East coast, comes with a much more benevolent and common reason that continues to draw people, which is this desire to save what remains of the wilderness. You know, there’s often a sense from outsiders that, “Oh, I need to come and help somehow.” And his idea, he’s going to come and rescue predators, create a — at that time, wolf and grizzly bear populations were nearly extinct — and so that the movement to to help animals was very new. And he comes with that desire.

Duane comes with a much more mundane desire to just start over and recreate his life alone in the woods like a dream that I think most people have felt at least once in a while in their life, you know, when things aren’t going well, “I could go off.”

And to me, all of those urges, there’s a tragedy inherent in them, because we need community just as much as we need connection to the natural world, and all the different things that bring people to Montana are often what keep them from ever seeing Montana for what it truly is. They’re drawn by a fantasy, and then the fantasy defines the place for them evermore. And so to me, the heart of this book was trying to unpack the tragedy inherent in the waves of settlers that have been coming to Montana for the last 200 years.

Matt Gallagher: You also mentioned in your essay that you were still working on the book when Kaczynski died last year by suicide. Did the book change at all for you when that happened? Were you tempted to change it? What kind of impact did that real life event have on your fiction?

ML: I was still working on it, but it was pretty late in the revision game, and I think that, you know, I had, throughout the process, tried to insulate myself as much as I could from the idea of the reaction of the real Ted Kaczynski, who at that time was still alive, or what position that would take.

So in a sense it felt very fitting, because his urge to kill had initially been directed at himself. You know, the first things he wrote about in his diary when he was at the University of Michigan, the first mentions of killing were a desire to kill himself, and then that desire eventually unlocked his ability to murder. He wrote that, “If I’m ready to kill myself, I might as well kill someone else.” And so there was a sense that the one way it did feel important to me was through that act, it felt clear that this person had not really changed through all of his 25 years of incarceration.

And that was important to me, because I didn’t want to give this character any kind of a redemption arc, or any kind of a sense that he changed, because there was never any inkling in his journals that he did, or in his public statements, that he understood the incredible pain that he had caused, or that he was coming to some deeper understanding of what it is to be a human being among other human beings. And so to me, it represented that this was the same Ted that I had written. And so that came as a relief.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Vianna O’Hara.

*

Old King • Ruthie Fear • Come West and See • Opinion | The Unabomber and the Poisoned Dream of the American West – The New York Times

Others:

William Kittredge • Richard Hugo • Lewis and Clark • Billy the Kid • Jack Kerouac • “The Story of Jack and Neal: the friendship that made On the Road—and the Beat Generation—possible” by James Parker, The Atlantic, March 11, 2022

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.