About that time, Maud felt a tap on the shoulder. Jimmy Foreman, a good-looking, skinny boy she’d known most of her life, led her into the dirt. They joined a new square and danced two more dances before Jimmy was cut in on by Henry Swimmer and Henry was cut in on by John Leeds. Maud decided that she looked better on the floor than she would’ve looked standing around it and that dancing was the best place to be appreciated by Booker. She figured he must be looking on, even if, as her eyes searched the rims of the dance patch, she couldn’t locate him. The light was now entirely cast by lanterns. Maud couldn’t make out the blue except in her imagination. But she could see a canvas roll. Booker’s wagon was still there.

And it continued to be when the fiddlers broke and the dancers went off in clumps to drink lemonade or stronger brew sold out of trunks of cars. But Maud, instead of availing herself of any refreshment, took the break as an opportunity to do what she’d been wanting to do for at least five dances. That was to go to Booker if he wasn’t coming to her. But as soon as she reached an angle where she could see the wagon and its owner well enough, she realized that Booker was there to sell, not to dance. She felt foolish for having spent so much time thinking anything else. He was beside his wagon, holding a pot out to a woman she couldn’t place. But she could tell from a distance that he was reciting the advantages of that particular pot over all others on this earth or any other planet.

Maud felt a jab of jealousy. She fought an urge to stride over to the wagon, grab that pot and buy it herself. To contain that feeling, she looked around at the people who had wandered back of the stage, and she saw, at a distance, Billy Walkingstick. He was talking to two other boys she knew, but she also knew she could lure Billy even into a briar patch. So she walked in a direction that would both avoid the wagon and catch Billy’s eye, and, sure enough, like a bass following a lure, Billy disengaged himself from his friends, and shouted, “Hey, Maud, don’t be highfaluting.”

Maud replied, “Oh, Billy, you surprised me. I didn’t know you’d taken up square dancing.”

Billy said, “Haven’t. Didn’t have anything better to do. You been dancing?” He fell in next to Maud.

“A bit,” she said and kept walking. But then she suddenly stopped. “That peddler over there has something I want to look at.”

Billy said, “What is it?”

“Several things. Women like to look. You know that.” She took off toward Booker’s wagon.

Billy dropped his cigarette, crushed it with his boot, and caught up with Maud in a couple of long strides. She was pleased he did. His puppy eagerness and Indian good looks made him the perfect escort to be seen with.

She went straight to the Woodbury soap. She picked up a bar, read its wrapper and held it close to her nose for a sniff. Booker was making change with his back to her. She was afraid he wouldn’t turn her way until she sniffed the bar silly, so as soon as that transaction was closed, she said, “How much did you say this was?”

Booker turned around slowly. He looked at Maud’s face and then at the item she held in her hand. He stretched his hand out to hers, brushed it slightly, and said, “Let me see.” He turned the bar over and found 5 c marked on the back. He said “A nickel, normally, but for you 2 cents.” He touched the rim of his bowler and smiled. Then he turned to Billy. “Howdy. Are you Maud’s brother?”

Maud inserted, “No, a friend. This is William Watie Walkingstick. He goes by Billy.”

Billy brought the fingers of his left hand to the rim of his cowboy hat and inserted his right hand into his front pocket. He said, “I’ll pay full price for that.” He drew out a nickel.

Booker took the coin with one hand and delivered the bar to Billy with the other. “Glad to do business with you, Mr. Walkingstick. Fancy anything else for your girl?”

Maud made a noise that was more of a catfish growl than a word. Both men jerked a little and looked to the source. Maud knew she was turning red. She hoped the dark of the night and the dark of her skin were combining to protect her. She said, “Thank you, Billy,” and held her hand out for the bar. To Booker she said, “He’s one of my oldest friends. Fishes with my brother.”

Booker said, “I see.” Maud hoped both that he did see and didn’t. And she was trying to sort out some kind of response that would straighten things out, but not give her away, when Billy said, “You sell soft drinks?”

“No, they’re not in my line.” Booker shook his head.

Maud said, “He mostly trucks in books. Booker, would you show Billy your books?”

Booker held out his arm toward the side of the wagon facing the back of the stage. He said, “What kinds of books do you like to read?”

Billy said, “Whatchya’ got?”

Booker, in a sing-song cadence that spoke of practice, recited a litany of books, and Billy’s eyes took on a glassy gaze. But shortly into that, to insert herself back into Booker’s attention and also to get Billy off the hook, Maud said, “My uncle was telling me about a book that escaped the fire. Did you hear about that?”

“Heard about the fire. Hard not to.” Booker had a smile on his face.

“I meant, did you hear about the book?”

“No. I assumed all the books were burned. I went by there the day afterwards. It was a mess if I ever saw one. You can even see the pile from the bridge.”

“You’ve been over the bridge?”

“Went to Muskogee. Had to pick up more goods at the railway station.”

“I’m surprised you didn’t stay over there.”

“I did for a couple of days. But I wasn’t having much luck competing against the stores.”

Billy said, “How much will ya’ take fer this book here?”

Maud had forgotten about Billy. And she’d never known him to read a lick. She said, “What is it?”

“Lasso tricks. See here?” He held out a page illustrated with several pair of hands and ropes in different positions. “It shows all the angles.”

Maud pretended interest in the pictures, and Booker named a price. Billy pulled more coins out to pay and then stuffed the book into his right hip pocket. Maud couldn’t see a graceful way back to the original conversation. Worse, she didn’t see any way to dump Billy without looking heartless, and she knew males sometimes sided with each other in their sympathies, even if they were rivals. She didn’t want to look cruel, but she didn’t want to leave. So she was stuck. And she was fishing around for something to remark on when a commotion arose on the other side of the wagon. Booker said, “Excuse me,” and stepped away.

Maud was still on the book side of the rig, her view blocked by the pyramid, when she heard an official-sounding voice: “Are you Mr. Booker Wakefield?”

Both she and Billy moved toward the voice, and Booker said, “Yes, sir. What can I do for you?”

“You can come with me.”

Maud knew the sheriff. And she was about to say, “That’s just stupid gossip,” when Booker said, “What for?”

“It’s about the school burning.”

Booker rubbed the back of his neck. Then he laid his hand on the edge of his wagon and gripped it, his elbow stiff. “Do you have probable cause?”

The sheriff said, “Do ya’ want to come peacefully, or should I persuade you?” He put his hand on the butt of his gun.

The crowd had grown thicker. The faces were lit by lanterns. Most were women of childbearing age with little ones at their skirts. Husbands were sprinkled around in groups behind their wives. The deputy was at the sheriff’s right shoulder. Booker said, “I need to close up. I can’t leave my wares.”

Maud felt heat rising up beneath her dress and her slip and, with it, the urge to blurt out, “That silly woman just wants attention.” But she realized that accusation would only complicate the situation and she didn’t have any proof except her intuition. Besides, she knew that it made matters worse that she was there, that men hated to be humiliated in front of women. She felt embarrassed for Booker and wanted to back away, to disappear, and then to reappear again, maybe at the jail, to save the day. But she also recognized that was a foolish desire. Heroic moments happened only on the pages of books. She touched Billy on the arm and jerked her head as a signal to step away.

They moved outside of the ring of light, and Maud watched without speaking as Booker, in silence, rolled down the netting over his goods, rolled down the bright blue canvas, killed his lanterns’ lights and hung the lanterns on hooks on the side of his wagon. By the time that was done, most of the crowd had dispersed and one child’s voice was yelling in the distance, “They’ve arrested the drummer!” Only the glow of the dim yellow lights of the dancing patch remained in the air. Still that was light enough for Maud to see Booker look in her direction. As though they were alone in the world, he shook his head. She nodded and mouthed the words, I know. Then he climbed into the seat of his wagon, picked up the reins and, after the sheriff climbed in on the other side, flapped them and clucked at his horses.

Maud said to Billy, “There’s no justice in that. Some ignorant woman accused him and the sheriff needs someone to pin the fire on.”

Billy said, “What makes you so sure he’s innocent?”

“I don’t have to be sure. They have to be. That’s how the law works.”

“Really?” Billy looked at Maud sideways.

“Well, no. But that’s the way they tell it.”

“They tell a lot of things, Maud. None true as far as I’ve ever seen.”

There was no denying he was right. So she and Billy walked in silence around the back of the stage, up the side of the dance patch, and into the light again. Billy didn’t ask Maud to dance, but a couple of other boys did. She turned them down, watched Lovely dancing with Gilda through two songs, and then she and Billy walked down Lee Street, into the dark. They made a stop at the back end of a car. Then they sat on the front steps of a lawyer’s office, drank choc beer and smoked cigarettes. Eventually, they fell to necking, as, even to Maud, that seemed to be the only thing left to do.

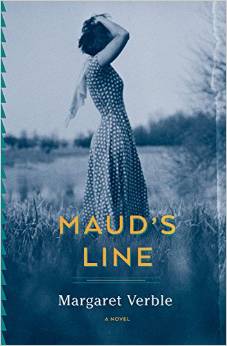

From MAUD’S LINE. Reprinted by arrangement with Janklow & Nesbit Associates, forthcoming from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Copyright © 2015 by Margaret Verble.