Matthew Salesses on Writing Plot and Cultural Context

"Acceptance and rejection are cultural."

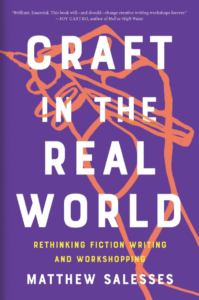

The following is excerpted from Matthew Salesses’ Craft in the Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing and Workshopping and first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Plot is typically taught as a causal string of events rising out of character. And this concept of plot is useful. It’s generally what Western readers expect. It’s self-contained. It creates resonance between earlier and later events. Each action a character takes gains suspense and stakes when it is expected to force further actions, to have larger consequences on the character’s world. Like each word in a language, each event in a character-driven plot holds meaning because of its place within a chain of connected events, which emphasizes that fiction is more than a set of conversations or happenings, that an individual’s choices have and make meaning.

Yet it’s about time that individual agency stops dominating how we think about plot or even causality. If we canonize E. M. Forster and Aristotle, it should be as representatives of one tradition among many. Aristotle famously put plot first in importance (when writing tragedy) and gave plot a shape and a purpose, and Forster focused plot on causation and character. (“The king died and then the queen died of grief” is a plot, he says, while “The king died and then the queen died” is merely a story.) But Aristotle put plot first because he didn’t personally like the dominance of theme in drama (and because, as Forster himself points out, drama shows action more easily than it shows thought). Aristotle complains that the tragedians of his day used plot not in service of an individual’s tragic agency, but as a way of stringing together various monologues and dialogues by theme. To him, an episodic plot in which a character faces a thematic series of problems rather than bringing those problems upon himself is the worst offense; a real tragedy is the result of a protagonist’s one tragic flaw.

Forster’s insistence on agency is really about audience. He believes that a series of events that are not causally connected (a war, then an earthquake, then two people falling in love) is for “stupid” readers. An “intelligent” reader’s goal is to solve the mystery of causality. It is this mystery that Forster relates to character — what he really means in his famous quote “incident springs out of character” is that the mystery should be human. He is making a claim about the world, that it is a matter of human agency. We may not agree. If I touch a window and it shatters, why should I make sense of this by thinking my touch caused the window to shatter? Why shouldn’t I think it was a coincidence, and even that the coincidence is what makes it meaningful? Forster and Aristotle object to a coincidental plot for moral reasons that have to do with their belief in the project of the individual.

As a child, I used to read fiction for exactly this sense of agency: to feel that the world, which felt so out of my control, could be controlled. To enter the books of my youth was to enter books in which a world was ordered around an individual. The protagonist walks through a door into a kingdom that has been waiting for just his appearance. Fictional protagonists often have vast incomprehensible power, enough to save worlds, because the worlds are theirs. The plots of these books support the idea that human agency is how to make sense of the human experience. They also support certain ideas about who should have that agency and who should not.

It’s no coincidence that most of these books were about well-off white kids. Whom were they written for? Believing that agency is heroic, I felt that my life was villainous. I wanted to change the world, rather than to accept or reject the consequences of living in it. Consequence, in my life, originated in systems of power — whether that meant my family, the adoption industry, the school system, hegemonic normativity, or so on. If we think of plot as acceptance or rejection of consequences, we take into account constant negotiations with power. Acceptance and rejection are often emotional, not active. Sometimes a character’s negotiations with power are part of a string of causation and sometimes not. To put plot in terms of acceptance and rejection is also to put plot in sociocultural context. Acceptance and rejection are cultural — they depend on positionality, geography, mental health, familial values, trauma, etc.

Causality is an important discussion in fiction, as is agency and separating plot from event. But if the axiom “start when all but the action is finished” is useful, it is possibly because being in the world is much more about dealing with effects than with causes. Fiction in which the world is constantly putting demands on characters, rather than the other way around — like a plague or global warming or fascism — is equally as compelling and true (if not more so to certain audiences). The hero story is its own fantasy. Coincidence, routine, unexplainable emotion, even the weather, can be profound. The king dies, and then the queen dies, but the people still have laundry to do, children to feed, love to love, lives that continue in all directions, not each independent of the other, but more meaningful for how they intersect.

*

Read more on developing plot:

Rónán Hession on writing without an emphasis on plot.

Emily Barton on building momentum into a plot.

Lisa Cron on the effects of plot on readers.

Peter Ho Davies on the relationship between plot and family life.

*

3 Books Recommended by Matthew Salesses

Mo Yan, Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out

Alexander Chee, The Queen of the Night

Franz Kafka, The Trial

__________________________________

From Craft in the Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing and Workshopping by Matthew Salesses. Used with the permission of Catapult. Copyright © 2021 by Matthew Salesses.