Mary Laura Philpott on Facing the Unexpected and Absurd with Humor

The Author of Bomb Shelter In Conversation with Maggie Smith

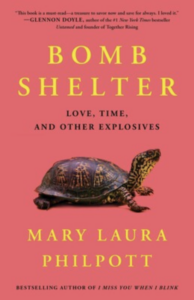

I’ve been a Mary Laura Philpott fan since reading I Miss You When I Blink, her bestselling collection of essays; her new memoir, Bomb Shelter: Love, Time, and Other Explosives, has solidified her as one of my favorite essayists writing today. Bomb Shelter asks—and attempts to answer—questions we all ask ourselves: How do we cope with the unexpected? How do we feel secure when so much is unknown? How do we find the hope and courage to keep building our lives when the ground seems to be shifting beneath us? Philpott as narrator of her own story is vulnerable and candid, and this book, like life, is prismatic: tender and heartbreaking and funny as hell.

Philpott is brilliant in prose, but let me say this: There is a lot of poet inside this writer. She knows when to let a detail release meaning rather than spelling things out for us. She threads apt images and metaphors throughout her work, leaving a breadcrumb trail for observant readers to find (and, yes, geek out over).

I was lucky enough to talk to Mary Laura Philpott about Bomb Shelter via email, and we covered some of my favorite subjects: art, music, humor, parenthood, anxiety, and magical thinking.

*

Maggie Smith: OK, so as a poet, I have to ask you first about the epigraph, from Auden’s famous poem about the Brueghel painting.

Mary Laura Philpott: Oh, thank you, dear poet, for noticing such a detail!

In the painting Auden writes about in his poem “Musée des Beaux Arts”—Brueghel’s “The Fall of Icarus”—we see this sunshiny, seaside town going about its daily business while off in one little corner, just barely visible, there’s the splash of “Something amazing, a boy falling out the sky.” The painting and the poem both juxtapose mundane, everyday details—a guy pushing a cart along a path, a horse and some sheep meandering by—with this major, life-altering event. To me that’s so true. We’re all living in our own personal worlds, which can get blown to bits and re-arranged even as the larger world spins merrily on, oblivious. Ordinary things and extraordinary things are happening at the same time.

“I sometimes wonder if to some degree the sense of humor I get credit for actually comes down to people thinking I’m kidding when I’m just telling something as plain and real as I see it.”

If you want to be English-majory about it, you can find imagery from the poem echoing throughout the book. Auden depicts the boy’s “legs disappearing into the green water,” for example; and a few chapters into Bomb Shelter, you read about the morning I found my son unconscious on the bathroom floor, how I saw his feet and legs first, “swimming desperately against some dreamworld riptide.” I’ve always loved that poem, and when it popped into my head one night and I looked it up so I could remember it better, I was struck by so many eerie similarities to scenes I had already written in this book.

And of course, the reference to Icarus also hints at hubris, which is a recurring theme of Bomb Shelter’s emotional journey. One of the things I’m working toward in this memoir is letting go of the idea that I control as much as I imagine I do—that bad things happen because I “let” them and that if only I tried harder I could prevent all calamity and keep everyone safe forever. It’s such hubristic nonsense to think that I personally tempted fate by loving my people too much, so blammo, fate started striking down my loved ones.

MS: Did you see Elisa Gabbert’s piece in the New York Times about that poem?

MLP: I did! It’s fantastic. I’ve seen the poem pop up a few places lately, and it makes perfect sense that it would be re-entering the cultural conversation right now. Here we all are, each going about our existences, while somewhere, other peoples’ lives are being blown apart. What’s happening in Ukraine, for example, is so heartbreaking. It’s strange how many of the historical and hypothetical references in Bomb Shelter have become current again. “Bomb shelter” is more than a metaphor in this book; I write in one chapter about a literal bomb shelter that was part of my family history.

At the time I was writing that part, I thought I was going to have to ask people to use their memories and imaginations to recall what the height of the Cold War felt like. I never anticipated that feeling would be in the air again as this book comes out. I mean, in theory, everyone hopes their book will be relatable, but I wish that particular part weren’t quite so relevant today.

MS: I love memoirs-in-essays—they are so elastic in that they can expand to contain so much—different subjects, times, tones. Could you talk more about how you decided what to include in this memoir, and how you arranged the essays that became its chapters?

I love to read memoirs-in-essays, too, so maybe that’s part of why I’m drawn to writing them. I keep saying that Bomb Shelter crashed into my life and demanded to be written, because it seemed to have a life-engine of its own. One of the main things the me-character is figuring out how to do in this book—finding a way to peacefully, even joyfully, let go of people I love—had been on my mind for a while before I began writing. My children were getting older; my firstborn, my son, was halfway through high school and thus nearing the age when he would leave the nest. Plus my parents were getting older and my own body was aging. So I had this sense of a clock ticking toward all these endings.

Then one morning when my son was in tenth grade, my husband and I awoke to the horrific sound of his body hitting the tile bathroom floor. He was having what we would later learn was his first epileptic seizure. Suddenly the ticking of that clock got so much louder. It wasn’t just, “How can I let my babies go out into this wild, dangerous world?” but “We have two years until, best case scenario, he leaves home for college. How can I make sure he’s okay by then?” Everything I saw and thought about was filtered through this lens of wanting to keep everyone I loved safe.

I return to that story and those questions throughout the book, but many of the essay-chapters tell other stories: memories from the past, tales from my current life, dreams and worries about the future. The order and structure I put them in creates the “emotional plot,” as I like to call it—the story of this me-character experiencing a before-and-after moment, then going through all sorts of stages trying to reckon with it and find a way to move forward. I’m not generally a fan of puzzles, but I do love the puzzle of putting essay-chapters into order for a book.

MS: I, like you, am a worrier. I may be guilty of thinking of my own anxiety as a protection spell—as if I could think about something hard enough to control the outcome. I get the feeling that we have this in common?

MLP: I’m glad I’m not alone! The problem is that we’re not totally wrong. You and I both know that our ability to think ahead and plan our way out of danger actually is a protective mechanism. Humans don’t have hard shells or poisonous venom or enormous claws; what we have are our brains and their ability to store and recall lifesaving lessons. The difficulty for us comes in knowing how and when to turn that mechanism off. Driving at a reasonable speed on the highway so we don’t get in a wreck, that’s smart. But vividly imagining every different kind of car crash we could possibly have… that’s torture. And it’s exhausting.

But it’s also sort of funny, in a tragicomic way, isn’t it? I just finished watching a series on Apple TV called For All Mankind that’s set within NASA, and I repeatedly had to stop myself from studying the scenes in space as if I were going to be tested on them. I mean, I am never going to be an astronaut. I do not need to memorize how to repair a faulty valve on a moon rover. It’s absurd. Do you do this studying-for-every-scenario thing?

MS: Oh friend, I relate to some much of what you’re saying. I wouldn’t say I study for every scenario, but I definitely go there. How can we not play out various scenarios in our minds, especially as mothers? So much of this book is about caregiving and caretaking, and it seems to me that a huge part of parenting is imaginative: What could happen? What might be coming around the bend? And I don’t mean just anticipating danger, but also having hope for what the future might hold. Though sometimes hoping is scarier than worrying, isn’t it? What’s more vulnerable than hope?

MLP: Ain’t that the truth. It’s one thing to hope for your own future. To hope on behalf of your children is like laying your heart out in the middle of the street and holding your breath that cars won’t run over it. We human animals are hard-wired to try to prevent harm and pain from coming to our offspring, but we know it’s coming at some point, because pain comes for all of us. Chances are, though, that joy and love and success will also come along at various points. We have to grab the steering wheel of our imaginations and say, OK, aim your vivid picture-making capabilities this way for a minute—let’s envision some of the bright possibilities. There could be so many good surprises ahead, too.

“I love the interplay of light and dark. … Heartbreak and absurdity are all tangled up together.”

MS: Here’s to good surprises! One of the brightest, best surprises about your writing is your sense of humor and your candor. Could you talk a little about balancing the gravitas with a sense of buoyancy?

MLP: I think much of my sense of humor comes from my mom, who has a delightfully sharp, weird wit. Anyone who knows her would say she’s their funniest friend. She’s also hyper-observant and has a gift for language, so when she uses a colorful metaphor to describe someone, it’ll make you spit out your drink. Because I grew up absorbing that way of noticing and speaking, I think perhaps I don’t always register when I’m saying something that strikes other people as humorous. It boggles my mind a little that people keep calling Bomb Shelter a funny book. I mean, I do intend to be funny sometimes.

And I love the interplay of light and dark. That’s what I’m aiming for when I tell a story, because it’s what I love in other writers’ work and I think it’s a very true way of telling stories. Heartbreak and absurdity are all tangled up together. But I also sometimes wonder if to some degree the sense of humor I get credit for actually comes down to people thinking I’m kidding when I’m just telling something as plain and real as I see it. I love to make people laugh, but even I am surprised sometimes by what elicits that laughter… which is a strange but fun kind of surprise!

MS: I definitely laughed—and cried—while reading Bomb Shelter. When I reached this sentence in your book, I felt so completely seen and known as a parent: “I felt the universe had entrusted me with so much more than I could possibly keep safe.” So, how do you make sense of this impossible task? Has writing helped at all? (*pen poised above page to take notes, because WOW do I struggle with this*)

MLP: You just said it: It’s an impossible task. This may seem counterintuitive, but for me, verbalizing that it’s impossible helps, because it keeps me from struggling against reality and becoming really disheartened. My mind leans hard toward magical thinking, so there’s part of me always thinking, “I can do this. I can keep my children alive and my parents alive and everyone else alive, and for that matter, if I try hard enough, I should be able to figure out how to reverse this climate situation and put an end to war and… and… and…” No. I am one person, and I cannot keep everyone safe forever. No one can. What I can do is live with a daily intention to take care of who I can, where I can, when I can. If I reword the task in those terms, then I start to feel like, yes, I actually can do this. I’m doing it already, in fact! Writing Bomb Shelter—in addition to having lived through the events and time period I was writing about—helped nudge me along the path to that reframing.

MS: “What I can do is live with a daily intention to take care of who I can, where I can, when I can.” I need to write this down and post it by my desk, and magnet it to my fridge, because of course this means the self, too—taking care of ourselves. So wise. Bomb Shelter is full of wisdom readers can squirrel back into their own lives, but it’s also a beautiful work of literature. I’m dying to geek out and pick your brain about craft. You have a poet’s eye and a knack for being able to “say the big things small.” I’d love to hear you talk a little about the poetic aspects of your prose—imagery, metaphor, compression.

MLP: I am delighted to get dorky with you about this stuff. Early on in my education, I discovered I loved taking poems apart. I wrote my undergrad thesis on, if I’m recalling correctly, “Psychological Space in the Poetry of Sylvia Plath.” I think poetry appeals to my natural fondness for efficiency. In an excellent poem, every word is doing multiple jobs at once. Nothing is wasted, which makes every line more powerful. That power is what I’m going for in my writing.

I cannot have music on when I write, not even classical. It messes with the sound in my head. I need to be able to hear the rhythm and melody of the words as I put them together. How does the pace of a scene change when I break sentences differently? Where would a breath naturally fall if I chose shorter or longer words here? Can I make you literally feel differently as you read a certain part by changing how you breathe?

Although I realize most people are busy and read quickly, I tried to build Bomb Shelter such that if you did want to go full dweeb and read it slowly with a pencil in your hand, you’d have fun and find all sorts of treasure. Will anyone notice the way the opening and closing chapters are ordered so that they sort of mirror each other? Maybe not, but I enjoyed using structure to create that subtle reinforcement that life is cyclical—things come back around. My writer-self has all sorts of fun with the concept of foreshadowing in this book, in part to illustrate one of my character-self’s struggles, the frustrating desire to know what’s going to happen next.

MS: I love that. And I’ve loved having this conversation with you. I can’t wait to chat more in person one day.

MLP: Maggie, this has been an utter joy. I can’t think of anyone better to have nerdy poetic-

language conversation with! Thank you.

__________________________________

Bomb Shelter: Love, Time, and Other Explosives by Mary Laura Philpott is available via Atria Books.

Maggie Smith

Maggie Smith is the award-winning New York Times bestselling author of eight books of poetry and prose, including You Could Make This Place Beautiful, Good Bones, Goldenrod, Keep Moving, and My Thoughts Have Wings. A 2011 recipient of a Creative Writing Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, Smith has also received a Pushcart Prize, and numerous grants and awards from the Academy of American Poets, the Sustainable Arts Foundation, the Ohio Arts Council, the Greater Columbus Arts Council, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She has been widely published, appearing in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, The Nation, The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Best American Poetry, and more. You can follow her on social media @MaggieSmithPoet.