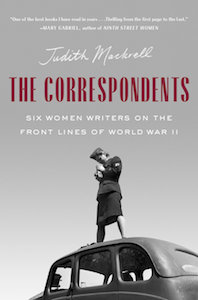

Marriage Story: On the Volatile Relationship Between Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway

Judith Mackrell Considers the Pair's "Crazy Honeymoon" and Gellhorn On-Assignment in China

Martha Gellhorn was surprised, at first, by the pleasure she got from becoming Mrs. Hemingway. The wedding had taken place on November 21, 1940—a modest event, held in the dining room of the Union Pacific Railroad at Cheyenne—and afterwards she’d written confidently to Eleanor Roosevelt, “Ernest and I belong tightly together. We are a good pair.” She believed she had gone into the marriage with open eyes, that she had fully got the measure of her husband, and that marrying did not have to spell the end of her independence, nor her ability to live “simple and straight.”

There had been difficult times, of course: Martha had felt both guilty and resentful when forced to resist Ernest’s hopes of a baby daughter; she’d suffered a shaming degree of bitterness when their respective war novels were published, and her own thin reviews for The Heart of Another were eclipsed by the tidal wave that had greeted For Whom the Bell Tolls. Marriage to a man whom the world regarded as a genius was evidently going to be hard. Ernest could be touchingly generous—“I have no greater joy than seeing your book develop so amazingly and beautifully,” he would tell her in 1943—and he could be devastatingly tender. “I love you,” he wrote, “because your feet are so long and because I can take care of you when you are sick, also because you are the most beautiful woman I have ever known.” But there were periods, too, when his volcanic brilliance was alarming to Martha, when she feared that he would eventually suck the oxygen from her own writing, her own ideas, and when she dared to wonder if she’d made the mistake of her life in marrying him.

She’d been especially ambivalent when, shortly after their marriage, Ernest declared his intention to travel with her on an assignment to the Far East. Two years had passed since her last major piece of reporting and, as she admitted to a friend, she was longing to “be a journalist again,” to have “that life of rushing and asking questions” and being in the places “where it is all blowing up.” Early in 1941, she arranged with Collier’s to write about Japan’s imperialist ambitions, its invasion of China and its threats to other countries in the region. Ernest, however, was worried that Martha was exposing herself to danger, undertaking “a son of a bitching dangerous assignment in a shit filled country,” and, without informing her, he got himself a contract with PM to cover the same story. It would be a “crazy honeymoon,” he’d said cheerfully when telling Martha of his plan, and she had not known whether to be touched by his concern or infuriated by the arrogance with which he’d muscled in on her trip.

In fact, Ernest did little reporting when they arrived at their first destination, Hong Kong. He fell in with a group of local boxers and policemen, who kept him busy with drinking and pheasant shoots, and Martha was left to follow her own instincts as she explored the city. She ventured into a brothel and an opium den, where she watched a 14-year-old girl, with a pet tortoise, expertly filling the clients’ pipes; she got herself lost in alleyways and street markets, and she took detailed notes about the families who squatted in derelict buildings, the children put to work in sweatshops. The poverty of Hong Kong appalled her, but she was entranced by the otherness of this “rich and rare and startling and complicated city.” “I go about dazed and open mouthed,” she wrote. “Everything smells terrific. I have never been happier, only a little weary.”

But Martha had come east for a war story and, while in Hong Kong, she was offered a freezing 16-hour flight over mainland China to get an aerial view of its battle-ravaged landscape. In 1931, when the first Japanese raids had begun on Chinese soil, Martha had paid no more attention than the majority of the Western world. Now, with Emperor Hirohito in alliance with Hitler, and making open threats on American and British colonies, she understood that the Far East could no longer be safely or decently ignored. Indeed, when she and Ernest sailed to mainland China in early March, Martha had already framed the conflict with Japan as a re-run of the Spanish war, a free and innocent nation invaded by a barbarous, bullying dictator.

Her sympathies were severely tested, though, as she and Ernest made the arduous journey up to the Seventh War Zone, sailing part of the way in a rickety, crowded boat whose noxious fumes made her retch, then switching to a pair of “obstinate, iron mouthed and mean natured ponies.” The Zone turned out to be huge, the size of Belgium, and with the fighting having stalled in intractable mountainous terrain, the only action Martha saw was a simulated attack, executed by very young Chinese soldiers, who looked to her like “sad orphanage boys” in their skimpy uniforms.

Their tour of the region started to feel interminable, as every stop they made, every barracks they visited, came with a seemingly endless banquet, and Martha had to force down dishes of sea slugs and drink the local delicacy of “cuckoo”-infused wine. Her hands had become virulent with a peeling fungal infection which she had to treat with an evil-smelling ointment. Lying on the wooden board that passed for her bed in one guest house, and feebly swatting away mosquitoes, she swore to a heartlessly amused Ernest that she wanted to die.

“Too late,” he grinned. “Who wanted to come to China?” But more dispiriting than the physical discomfort was the corruption they discovered at the heart of this war. China’s weak showing against Japan was not solely the result of poor equipment and bungled strategy, for its leader and war general, Chiang Kai-shek, was deliberately undermining his own army. As an official ally of America, Chiang had benefited from generous US aid, but, rather than using it for the good of his country, he’d been pocketing some for himself and using the rest to fund his own personal war on Chinese Communist insurgents.

She had not known whether to be touched by his concern or infuriated by the arrogance with which he’d muscled in on her trip.Martha and Ernest were invited to lunch with the General and his impeccably groomed wife, and found the opulence of their Chungking residence in grotesque contrast to the poverty outside, and when Martha dared to enquire about the community of lepers who were begging nearby, she was met with a frigid stare. The Chiangs revolted her—“Their will to power was a thing of stone,” she decided—and she despised their callous sense of entitlement even more when, in great secrecy, she and Ernest were taken to meet Zhou Enlai, international representative of the Chinese Communist Party. Despite his filthy tattered uniform, Zhou was a compelling figure, a very handsome man, with “brilliant amused eyes” and an irresistible aura of mission. Martha thought him “the one really good man” she’d met in China, yet she knew it was impossible for her to promote his cause. America had invested too much in Chiang for Collier’s ever to consider publishing the “straight truth,” and just as she could not write about the corruption of Chiang’s regime, so she could not comment on the righteousness of those who rebelled against it.

Ernest, meanwhile, had proved his worth as a travel companion. Although he too had complained viciously about the food and the bed bugs in mainland China, he’d laughed Martha out of her misery and had given her wise, sympathetic counsel about how to write her compromised report. At moments, the trip had actually felt like the “crazy honeymoon” he’d promised, and, after he’d left Martha to complete her tour of Burma, Singapore and the Dutch East Indies, he’d written to remind her of how good they’d been together: “I am lost without you… just straight aching miss you all the time. And with you I have so much fun, even on such a lousy trip.”

Martha had missed Ernest too, but her pleasure in their reunion was diluted by the shame of her China article. “You have to be very young, very cynical and very ignorant to enjoy writing journalism these days,” she wrote to her friend and one-time lover, Allen Grover. She knew that her integrity, her writing had been tainted, and her despondency over China began to leak into her perceptions of the European war. She felt, as she had in the horrible autumn of 1938, that she was unable to judge confidently between right and wrong, and she feared now that, even if Hitler were eventually defeated, the evil he’d unleashed would remain in the world, “like an infection of the blood.” On December 7th, Pearl Harbor was bombed, and at Christmas Virginia came to stay in Cuba, celebrating the end of her American book tour. But a “cosmic indifference” had settled over Martha, and she believed she was finally done with journalism, and finally done with wars.

*

In the end, it was Ernest—or, rather, her frustrations with Ernest—that changed her mind. On their return from China, he’d drifted—squandering days at a time with his boating buddies, barely touching his typewriter, and unable to access the white-hot focus with which he’d written For Whom the Bell Tolls. Yet, if Martha ever dared ask if he had a new project in mind, he reacted with disproportionate viciousness. She was a “conceited bitch,” he raged, for presuming to question his work and, hatefully, he reminded her of the disparity in their literary reputations—“they’ll be reading my stuff long after the worms have finished with you.” If Martha had been a very different kind of woman—more saintly, more gentle and without a talent of her own to defend—she might have coaxed Ernest into admitting the fears that needled him to so violent an overreaction. She might have realized that beneath his bluster lay a terror of failure, a terror that he would wake up one day and find that his gift had deserted him and all his words had gone. She might have realized, too, that he was equally afraid of his own nature. His father, cursed with depression, had killed himself, and Ernest sensed that the darkness was inside himself as well. But weakness was difficult to admit, especially when Martha was at her most impatiently judgmental. Instead, Ernest turned away from her, and when America went to war, in December 1941, he furnished himself with the perfect excuse for both ignoring her and neglecting his writing.

Cuba and its surrounding waters had suddenly become targets for German attack and, inspired by rumored sightings of Nazi agents and lurking U-boats, Ernest had formed a sea patrol unit, using his own boat Pilar and enlisting the help of eight other crew. He thrilled to the idea of being a man of action again, especially since a $500 monthly stipend from Central American Naval Intelligence allowed him to furnish his self-styled “Crook Shop” with an armory of bazookas, grenades and machine guns. Martha, however, was skeptical. Early in January 1942, she’d been commissioned by Collier’s to do some submarine hunting of her own, but had been rewarded with nothing but a dose of dengue fever.

Ernest and his Crook Shop fared no better, and, as the months passed, Martha could not help but dismiss his activities as a machismo fantasy. She’d tried to suppress her doubts, concentrating on the completion of her latest novel, about a young French Caribbean woman, torn between money and love. But once the manuscript was with her publishers, she had nothing to think about except Ernest, and the barbs of distrust and disillusionment between them. It seemed to Martha a long time since she’d been able to feel or think “straight,” and, in September 1943, when Collier’s suggested a prolonged assignment in Europe, she was happy to immerse herself back in events which were so much larger, and more important, than her marriage.

Initially, she’d hoped to make Ernest come with her, and had even suggested he might write one or two of the pieces Collier’s had proposed. It would be a way for them to rekindle the crazed hilarity of China, the purposefulness of Spain. But Ernest was angry. He was offended, first, by Martha’s assumption that he could so readily abandon his spy-hunting, yet he minded even more that she would consider going to Europe without him. The barbed resentments became a thicket of spite: Martha accused Ernest of being drunk and deluded, he retaliated by calling her a selfish, unnatural wife, and, most woundingly of all, a moral hypocrite, who only went chasing after war because she was greedy for fame.

By the time Martha left for New York to catch her Pan Am Clipper flight, she’d re-established peace. “We have a good wide life ahead of us,” she promised, “we will write books and see the autumns together and walk around the cornfield waiting for pheasants and we will be very cozy.” Yet, it was impossible for her to disguise the lift of excitement in the letters she wrote to Ernest during her journey. The two of them had agreed on a code that would tell him where she might travel after London—a reference to Herbert Matthews meant Italy, one to the photographer Robert Capa meant North Africa—and Martha longed to see both. “I am happy as a firehorse, feeling ahead already the strange places,” she admitted, and even now the distance between her and Ernest was threatening to stretch longer than the promised three months.

__________________________________

From The Correspondents by Judith Mackrell. Copyright © 2021 by Judith Mackrell. Published by arrangement with Doubleday, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.