Mark Twain disliked suspenders so much that he invented the bra clasp. (That’s right.)

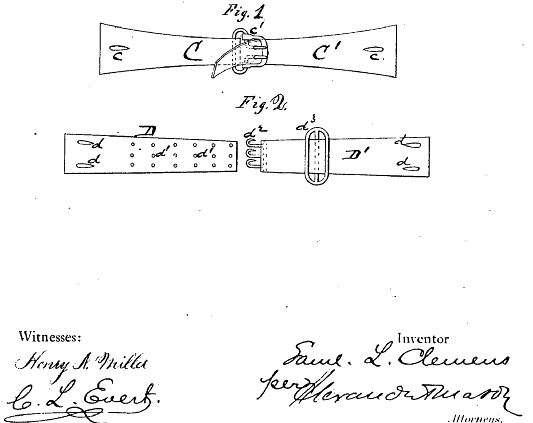

Here’s your fun fact for the day: Not only was Mark Twain (née Samuel Langhorne Clemens on this day in 1835) an inventor of good stories and witty rejoinders, he was a literal inventor—of both successful and not-so-successful items. Over the course of his life, he registered three patents: the first, in 1871, was for an “Improvement in adjustable and detachable straps for garments,” meant to be an alternative to suspenders, which Clemens apparently found uncomfortable.

“The nature of my invention consists in an adjustable and detachable elastic strap for vests, pantaloons, or other garments requiring straps as will be hereinafter more fully set forth,” he wrote in the patent abstract.

It is obvious that my adjustable straps may be made non-elastic as well as elastic without departing from my invention; but I prefer to make them elastic.

The vest pantaloons or other garment upon which my strap is to be used should be provided with buttons or other fastenings on which the strap is to be detachable and adjusted. When changing garments the strap may readily be detached from one and put on another.

The advantages of such an adjustable and detachable elastic strap are so obvious that they need no explanation.

The invention didn’t catch on for any of its intended pantaloon and vest-related purposes, but as it turned out the advantages were obvious, at least for a certain item that Twain didn’t even think of. “This clever invention only caught on for one snug garment: the bra,” wrote Rebecca Greenfield in The Atlantic. “For those with little brassiere experience, not a button, nor a snap, but a clasp is all that secures that elastic band, which holds up women’s breasts. So not-so-dexterous ladies and gents, you can thank Mark Twain for that.”

Twain’s second patent, issued in 1873, was more successful, and actually made him some (badly needed) money: in 1873, he invented a “self-pasting” scrapbook, whose pages came pre-gummed, like a lickable stamp. It was produced and sold and proved popular—by 1885 he had reportedly made $50,000 through sales—though users soon found that it did not do well in humid weather.

Still, the utility of this item was just as obvious as the garment strap. As Twain wrote in an advertisement for the scrapbook: “You know when the average man wants to put something in his scrap book he can’t find his paste—then he swears; or if he finds it, it is dried so hard that it is only fit to eat—then he swears; if he uses mucilage it mingles with the ink, and next year he can’t read his scrap—the result is barrels and barrels of profanity.” Mark Twain, saving the world from bad language yet again.