Marion Winik on Marrying a Gay Man, Telling Secrets, and Writing Fiction Versus Nonfiction

“I did my best to present Tony in a way that would make readers fall in love with him just as I had, and forgive his mistakes, just as I did.”

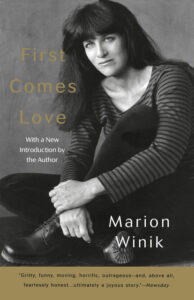

First Comes Love is a memoir about my marriage to Tony Heubach, a gay man, chronicling our meeting at Mardi Gras in 1983 and all the adventures and misadventures that followed. We found out Tony was HIV positive early on, but he was healthy for years and neither I nor our two sons ever contracted the virus—one of many unlikely turns of events that are part of this story. The book was published two years after he died in 1994, when our sons were four and six. To mark the 30th anniversary, it is being reissued.

First Comes Love started life as a novel. I began writing it in the early 1990s, when the now-crowded genre of brutally self-revealing memoirs barely existed; I didn’t then think you could write the kind of things that are recounted in its pages outside the protective cover of fiction. In my first book, Telling, a collection of candid personal essays published two years earlier, I was not actually quite as brave and forthcoming as it seemed. Rather than say my husband, Tony, was gay, I called him “a sexually ambiguous ice-skating bartender.” I never mentioned AIDS at all. It wasn’t my secret to tell. At least not yet.

I wrote First Comes Love imagining it would be published as a novel, though it did not in fact contain a lot of fiction. I changed names, occasionally imagined other people’s thoughts, wrote a few scenes describing events as if I were there when I actually wasn’t. My publisher said they loved the pages, but when it came time to finalize terms and sign the contract, my editor, Robin Desser, explained that she and the house would not feel it best to present the book as fiction, saying that this crazy, impossible-sounding story was interesting precisely because it was true.

Tony had been an enthusiastic collaborator on early drafts, telling me stories about his life before we met, also reminding me of things that had happened I might wish to add to the book. But by the time this publishing conversation happened, he’d been dead for about a year. I wrote Robin an impassioned letter explaining that it was morally, creatively, and legally impossible for me to publish the story as nonfiction. It wasn’t only because, with him gone, sharing the details of his private life and our bad behavior was a daunting prospect. In addition, assisted suicide, which is right there in chapter one, was a felony in Texas.

With the AIDS epidemic at its peak, tens of thousands of people were facing the agony of its final scenes.

Yet it was around that issue that I found my courage at last. The infuriating obstacles we encountered and hoops we had to jump through are described in detail in the book; here I’ll just say that by the time we finally managed it, I felt compelled to speak out. With the AIDS epidemic at its peak, tens of thousands of people were facing the agony of its final scenes.

I had by then been telling stories about my life on National Public Radio’s All Things Considered for several years. Back then, ATC ran short commentaries from writers like Bailey White, David Sedaris, Ellen Gilchrist, and Andrei Codrescu at the half-hour break. I had joined the group in 1991, so it seemed I had the ideal platform on which to take a stand.

NPR, however, wasn’t so sure. Their legal department strongly advised me not to endanger myself by airing it; I could become a target for right-wing activists and possibly get arrested. Filled to the brim with grief and rage, I was willing to take the risk and also hoped that in a liberal city like Austin, Texas, where I was a minor local celebrity, there would be little chance of enforcement action against me.

As it turned out, although the Houston Chronicle did run a front-page story about my “confession,” that was all. Instead of censure or criminal charges, I received many letters of condolence and support from people who heard the piece on the air, people who felt close to us because of the stories I’d been telling. I occasionally still meet people who remember hearing the commentary.

It was time to put the perceived legal, moral, and creative impossibilities aside. I did my best to present Tony in a way that would make readers fall in love with him just as I had, and forgive his mistakes, just as I did. As for my own mistakes, which were numerous and appalling, I had to find a balance between self-implication and losing the reader’s sympathy altogether. This was tricky—in fact, it’s an issue I’ve been discussing with students in memoir workshops for decades now—and I may have erred slightly on the side of ruthlessness.

Despite the concerns about fiction versus nonfiction, First Comes Love wound up containing a little fiction after all. I wrote from the heart, with as much honesty as I could. The problem is, you can only tell the truth you know. There were things I didn’t know at age thirty-four, when I was writing this book. And the way I found out one particular thing might be worth noting here.

Just a week or two before the book came out, I was surprised, and a little worried, to learn that I’d been invited to appear on Oprah’s afternoon talk show. This was before she had her now-famous book club, and I had never heard of an author, other than a cookbook or self-help author, appearing on her show. Adding to my hesitation was that I’d been told that the segment’s focus was going to be “straight women who married gay men,” and the producers wanted me to help them find other guests.

It seemed to me that most people in this situation, especially those without a book to promote, would not want to go on national television and discuss their personal lives. But my publicists saw this as a great opportunity, and I was under pressure to come up with something. I remembered that Margaret Moser, my editor at the Austin Chronicle, had told me that her father, brother, and first husband were all gay. I suggested the Oprah producers contact her, and to her delight, she was flown to Chicago to be part of the show. I also suggested another friend, Kerry Jaggers, a gay man I knew. He might know somebody who could be germane to the conversation.

We were pretty close to the shooting date when the producer called me. “You know, I still haven’t had a chance to read your book,” she said, “but I understand that it’s about your monogamous marriage to a gay man, right?”

“Yes,” I replied. “Well, monogamous until 1992, of course, when things really went to hell. But that’s all in the book. When you read it—”

“This is going to sound funny,” she said, “but I’ve been on the phone all morning with a guy in San Francisco who says he was your husband’s lover for years.”

The truth I was telling was my truth, not Tony’s. But this is just one of the many predicaments of writing memoir.

Kerry later insisted he thought I knew about him and Tony all along, but I didn’t believe him. “Anyway,” he said, trying to comfort me, “We weren’t really lovers. We were fuckbuddies.”

Fortunately, this topic did not come up on the show, which as I suspected really was not about my book. It was, as I’d been told, a sort of grab-bag about what the show’s expert called “Mixed Orientation Marriages.” Oprah and I had our best moment off-camera, when she said she loved my blouse. The day before, I’d spent $500, probably the most I’d ever spent on a piece of clothing by $475, on a periwinkle silk-shantung Isaac Mizrahi tunic at Bergdorf Goodman. I appreciated the compliment.

Reading First Comes Love now, I see that all the evidence of who Tony really was was there from . . . well, from the first, you might say. All those times he disappeared overnight . . . all those years when he seemed to not care about sex at all. . . . at times, my naiveté seems truly laughable. (The relevant sentences are now underlined in my copy.)

When the book was first published, I remember being surprised that some gay readers seemed ambivalent about it. Now I think they were probably put off by my assertions about our monogamy and Tony’s sudden-onset “asexuality.” The truth I was telling was my truth, not Tony’s. But this is just one of the many predicaments of writing memoir.

Dear, dear, Tony. It is my pleasure to introduce him to you. As I write this, his sons Hayes and Vince are thirty-seven and thirty-five, and he has two grandchildren, and perhaps someday we will take them to see his square on the AIDS quilt. It is terrible to think of what we lost when this generation was decimated. But it is also very sweet to bring back the long-lost world of the 1980s, with the Weather Girls raining men, the Pointer Sisters jumping for their love, beautiful Tony right before my besotted eyes, and Sylvester asking do we wanna funk.

Please, go right ahead.

__________________________________

This is adapted from a new introduction to First Comes Love by Marion Winik. Reprinted by permission of Vintage, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Introduction copyright © 2025 by Marion Winik.

Audio excerpted with permission of Penguin Random House Audio from FIRST COMES LOVE Marion Winik, excerpt read by the author ℗ 2025 Penguin Random House, LLC. All rights reserved.

Marion Winik

University of Baltimore professor Marion Winik is the author of The Big Book of the Dead, First Comes Love, Above Us Only Sky, and other books. She writes a monthly column at BaltimoreFishbowl.com; her essays have been published in The New York Times Magazine, The Sun, and elsewhere. A board member of the National Book Critics Circle, she reviews books for People, The Washington Post, Kirkus Reviews, and The Weekly Reader podcast. More info at marionwinik.com.