Marguerite Sheffer on Crafting a Collection of Century-Spanning Speculative Fiction

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of “The Man in the Banana Trees”

“Where were you when you learned you had won this year’s Iowa Short Fiction award?” was my first question for Marguerite Sheffer. “I was at work, in a team meeting at my day-job, at Tulane University’s Taylor Center for Social Innovation and Design Thinking,” she answered. “I got an email from Jim McCoy, the Editor at the University of Iowa Press, asking me to give him a call. I froze, then left the meeting.”

And your reaction? “It’s hard to explain how very surprised I was when he told me The Man in the Banana Trees had won and would be published. I had submitted the collection before I felt ready, because I was such an immense fan of Jamil Jan Kochai’s work—he was that year’s judge. And because it was free: why not? I hadn’t actually been thinking about the stories as a ‘collection’ until the opportunity arose to submit them.”

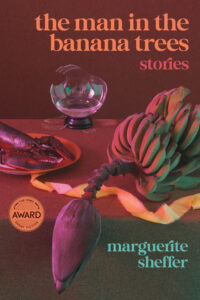

And the impact of the award? “I’m still finding that out! My day to day is still largely the same: work, trying to carve out time for reading and writing. I’ve gotten to hold the book in my hands, and it is beautiful. As someone who covets books, it is an incredible feeling to see these sentences and stories I worked on for years become this gorgeous physical book. I hope it finds readers; I hope readers treasure it too. It is out of my control now, and I am curious and excited to watch it make its way into the world. You might need to ask me again in a year!”

The Man in the Banana Trees is a time-traveling gem of a story collection spanning centuries, reaching from the Earth into Jupiter’s orbit, a continual speculative surprise with ghosts, a love triangle among scientific researchers, Unicorn tapestries, an artists’ colony in the Gulf South, a tiger, and a yellow ball python. Our conversation spanned the continent, connecting Sheffer in New Orleans with Sonoma County.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have these years of Covid and conflict affected your life and work, the writing of and launch of your first story collection?

The characters in The Man in the Banana Trees sometimes try to set care aside, but that doesn’t go well for them. The collection is full of inconvenient, ineffectual but heartfelt love.

Marguerite Sheffer: After ten years (since college!) I returned to writing during the start of the Covid pandemic. My workload, at the time for an education nonprofit, had shrunk dramatically, my commute disappeared. Suddenly I had all this time on my hands. I started a low-residency MFA, at the incredible Randolph College, which, in my first semester, was remote and virtual. I wrote feverishly. It has been strange to go through a period of creative growth, with all the joy and fulfillment that brings, at a time of so much collective turmoil and grieving. But also, writing has been something that helps me make sense of that. I often write horror or science fiction, and those modes feel right for processing the last few years, when so much injustice has been unmasked.

I also teach college students, and many of them have been disillusioned by the failure of those in power to protect them from Covid, to support them and their education. It’s more clear to them, I think, than it was to me at their age, how flimsy and corrupt our systems are. And I admire that clear-sightedness. What will they do with it? I’m excited to see.

JC: When did you write your first short story? What was it about?

MS: My very first short story that I remember writing was in fifth grade, historical fiction. It had this one image I remember very vividly: of a young girl who worked at a winery breaking these wine bottles, which broke, and she cut her bare feet on the glass. Why did I write that? I have no idea. But my teacher was proud of it and asked me to read it aloud to the class. I was too scared to do it, so the compromise we came up with was that he would read it aloud to the class, while I hid in the bathroom, which shared a wall with the classroom (it was one of those portable classrooms). So I sat on the floor of the bathroom, with my ear pressed against the door, trying to hear the words. Looking back, I can recognize that irrational terror as a sign of how much I cared about that story. I wanted to write it, I wanted other people to read it, but I almost couldn’t bear the intensity of being in that moment when they read it.

JC: Which writers have you turned to as influences on your work?

MS: I was lucky to have incredible mentors at the world’s best, kindest MFA program at Randolph College. Anjali Sacheva, Maurice Carlos Ruffin, John Vercher, Crystal Hana Kim, Clare Beams, and Julia Phillips all had immense influences on my work, both because I find their short stories and novels so brave and thoughtful, and from their feedback on my works-in-progress. The two years I spent studying there were a bootcamp for my brain, and a huge gift. They are the writers I want to grow up to be: generous and expansive.

I write work that bends speculative, and authors like Ken Liu, Sofia Samatar, Kij Johnson, Ted Chiang, E. Lily Yu, Meg Elison, and George Saunders make me feel invincible, expand my understanding of what a short story can be and do. One favorite is a space opera short story, “Pizza Boy” by Meg Elison: her endings are always instructive for me, and that one in particular really soars. “Position” by Sabina Murray, which I first encountered in a Norton (I think) anthology in high school, is one of those stories that has stuck with me for years and years, and was a huge influence on the way the stories in The Man in the Banana Trees play with time and history. Kij Johnson’s story “The Horse Raiders” really floors me: it’s set in a world that is at once familiar and jarring.

I’m also very influenced by the writers in my writing groups, including Tierney Oberhammer, Corinne Cordasco-Pak, Amy Johnson, and Archita Mittra.

JC: When did you start writing the eighteen stories in The Man in the Banana Trees? Which story came first? Which came last? How did you decide the order?

MS: I mentioned I took a long break from writing, during the ten years I taught high school English. I loved teaching, but it was all consuming. Now, of course, I find myself writing a lot about classrooms and teachers, unpacking all that complexity. All 18 stories in The Man in the Banana Trees were written between 2020 and 2023 when I went back to school to get my MFA in my mid-thirties. Surrounding myself with people who wrote, who took writing seriously, who also devoted themselves to this crazy thing, helped me write ferociously.

The first story I began was “Tiger on my Roof,” which was also one of the last to be finished, taking more than thirty drafts and countless rounds of feedback from many early readers. Melissa Febos had been a visiting writer at my first (remote) Randolph MFA residency, and she suggested we all write a list of what we were scared to write, and write those stories. The topic of “Tiger”—a white teacher mourning, or struggling to mourn, the death of one of their Black students—was on my list, and so I started work on that story my very first week of returning to writing.

“Local Specialty,” about a tanker crash in New England and mutant lobsters, was the very last story to be added to the mix, and was a response to a prompt from a Dark Matter anthology, called The Off-Season, of “coastal new weird,” stories. That story was written in a fun mad-dash to make their submission deadline, and while it was rejected (warmly), I am now so glad I took on that challenge.

I thought about the order of the stories like songs on an album. I wanted to keep up readers’ engagement by intermixing longer stories with shorter, flash fiction interludes, jumping between genres, between darkness and levity, keeping readers on their toes. I chose to start with “Rickey” because that story, about a puppet student in a city high school, introduces the weirdness of the collection, lets readers know that genre fiction is on the table.

JC: What is the meaning of your epigraph, the lines, “ It is not your duty to finish the work, but neither are you free to neglect it.—Pirkei Avot 2:16.” The theme for the collection?

MS: Yes, it is definitely a theme for this collection of unlinked stories! I added that epigraph to The Man in the Banana Trees late in the game, though it has been a favorite quotation of mine for many years, written on the inside cover of many of my journals. Pirkei Avot is a collection of Rabbinical teachings, and “the work” in question is the work of healing the world, which is never done but also can never be set aside. The characters in The Man in the Banana Trees sometimes try to set care aside, but that doesn’t go well for them. The collection is full of inconvenient, ineffectual but heartfelt love. The clearest reflection of those lines, I think (today) is in “Tiger on My Roof” where the narrator learns that “it won’t be enough, and I still have to try anyway.”

JC: What was the seed for the title story? How did you determine its structure?

MS: “The Man in the Banana Trees” is autofiction, merging a classic fairytale into a real situation as a way of trying to make sense of something that at its core, doesn’t make much sense or is not fair. Fairytales aren’t fair. The structure is heavily inspired by Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House, which I had read just before. I wanted to try her approach of writing in fragments, each with a title, referencing fairytales and pop culture throughout, and re-arranging those fragments non-chronologically, as a way of looking at the same incident from different angles.

I drafted that piece basically at the same time as I was living the experience of having a miscarriage, writing the fragments in my journal, or on whatever paper was nearby. At first, they were just for me, but soon—and this became part of the piece, the thinking about the writing of the piece, which Machado also modeled for me—I started to feel like the fragments were building into something. It became a puzzle, which made something new out of the grief I was feeling at the time.

JC: You cover a wide variety of time zones in this collection. What inspired “The Unicorn in Captivity,” which ranges from 1493, when the eight panels of unicorn tapestries hang on stone walls for feast days, through 2073, when children view one remaining tapestry through plexiglass walls in their sunken city?

MS: “The Unicorn in Captivity” was directly inspired by a line from a 2005 New Yorker article by Richard Preston, “Capturing the Unicorn,” about the Unicorn Tapestries at the Cloisters, which I had loved for a long time. The line is:

“‘For his part, Oi-Cheong Lee felt his sense of time dissolve. ‘The time we spent with the tapestries was nothing—only a moment in the life of the tapestries,’ he said.’”

Originally, that was used as an epigraph for the story, but we were not able to get permission to include it in the collection. The seed was this idea that people’s whole lives, all the personal drama and historical movements and big stuff of the day, are just flashes in the long life of this tapestry. I wanted to try to write something from the perspective of the tapestry, with the tapestry as the time-traveling main character. I was fascinated by the idea that for something to survive those hundreds of years, people had to keep making efforts to protect it, through war, famine, revolution, and disaster—that even when things are really bad for human beings, some people have this sense of long-time, of something bigger than just their own survival or their society’s survival. Visiting museums or preserved places has always felt like the closest thing we have to time travel to me.

JC: “The Observer’s Cage” reaches back to a cinder block cabin an hour from Cambridge in 1967, where three researchers work with a pioneering telescope, precursor to the Palomar in San Diego. “Don’t imagine a disk; don’t imagine a chalice embracing the sky,” your narrator explains. “Instead imagine a grotesque grid of wire and sticks. Like a labyrinth made of fencing, always listening. The posts kept the wires up and out of the moisture of the grasses, at an elevation of about five feet. You see, the telescope ran on radio, so the grid was cast over a wide area of the countryside. A big net to catch radio waves. The Four-Acre Telescope, we called it.” It’s about a momentous scientific discovery from outer space, and a love triangle—Ernie, an astronomer on the faculty at Cambridge, Lizzie, his “faculty wife,” even though the telescope was her design, based on Ernie’s research, and the narrator, their junior researcher. You mention in your acknowledgments that it is loosely based on “the discovery of pulsars by Jocelyn Bell Burnell in 1967, for which she was not awarded the Nobel Prize. The character of Lizzie is very different from Bell Burnell, in both personality and circumstance.” How did this story evolve?

MS: I was working on a completely different story, “Moonburn,” that might never see the light of day: a romantic story about telescopes and astronomers, and I was completely stuck. I went to the library and took out a book about the history of astronomy, and to try to get unstuck, I would read a few pages every morning, for weeks, just flipping to random pages. I wasn’t looking for anything in particular. As part of that research I read up about Jocelyn Bell Burnell, her discovery of pulsars using a telescope similar to the one in my story, ‘“The Observer’s Cage,” and the fact that while her male colleagues were awarded the Nobel Prize, she was not. I got that familiar tingly feeling, and started writing the story a few days later. The love triangle aspect and Lizzie’s character are a total creation, but very much sparked by that history. Something about the nature of pulsars, the idea of the universe as dynamic, energetic, and destructive: I wanted to explore that in the relationship between this trio of astronomers.

JC: Some of your stories seems to revolve around glimpses, images—a yellow-ball python in the parking lot at the Chipotle in “The Yellow Ball Python” (have you really seen one?); an oyster shell dug from the rough earth in “The Midden,” two strangers sharing photos on their phones in “Tiger on My Roof.” How does the visual influence your work? Do you use photos as part of your research?

MS: Visuals definitely influence my work. Many of my own memories are glimpses as you describe. For research, yes, the photographer in “In the Style of Miriam Ackerman” was inspired by Vivian Maier’s work, and “En Plein Air” was strongly and clearly based on the paintings by Clementine Hunter. I do think people, including my characters, attach great internal meaning to images. It can be easier to project what you are really thinking or feeling, those things you don’t want to face, onto a snake or a bird taking off. Symbols don’t just exist in literature, they’re part of how we move through the world. What I see and notice reveals my own obsessions, fears, and hopes. I’m interested in the fact that the “glimpses” you highlighted in your question are moments when one character is so stirred by something they’ve seen that they want to share it with someone else, to express something they can’t put into words.

I also had the amazing experience of working with a still life photographer, Jamie Chung who created the cover image for The Man in the Banana Trees. Getting to work with someone who is fluent in visuals, to think about how to represent both the vibes and some key symbols from the stories, was fascinating to me. I think he nailed it!

JC: Ghosts also appear, in what might be called haunted stories. “En Plein Air” is narrated by a ghost who has lingered for some 90 years on the artists’ colony of Ghassee Island. You mention it is “loosely inspired by the Natchitoches (Louisiana) Art Colony, and the now-renowned self-taught Black painter Clementine Hunter. How did you build this story?

Symbols don’t just exist in literature, they’re part of how we move through the world. What I see and notice reveals my own obsessions, fears, and hopes.

MS: “En Plein Air” went through quite a long process! The premise came quickly. I was visiting the art colony at Melrose Plantation (since renamed to Melrose on the Cane) in Natchitoches with a friend of mine, Nathan Marvin, who is a historian. We walked around the grounds, learned about the history of the colony. The major draw now is the work of Clementine Hunter, which is all over. She was very prolific. I asked myself what if (a lot of my stories start with what if’s) one of the ghosts of the white painters could see all the acclaim Hunter was getting, while their work, which was much more lauded at the time, is mostly forgotten and very definitely overshadowed. I thought the ghost would explode out of envy.

Over the process of actually writing the story, and creating the ghost character of Anne-Marie, she became more than a punchline. While she’s still deeply flawed, still plagued by jealousy and a limited worldview that wouldn’t let her see her Black maid as her artistic equal or superior, her ghostly nature gives her one more go to be able to reckon with the things she never could in life. The explosion I originally imagined for her became more of a surrender the longer I worked on the story, more of a true revelation that she gets to enjoy for a moment. The story was a tricky one for me because I wanted to lean into the uglinesses of her prejudices while also making her an intelligent and compelling person.

JC: How have literary communities like Third Lantern Lit, and the Nautilus and Wildcat writing groups, supported your work? And living in the vibrant literary universe of New Orleans?

MS: Writing with other writers has been instrumental. Our work can feel so isolating, and so crazy-making if you don’t have partners to debrief with, celebrate with, and offer perspectives. When people start talking about my characters like they are real people, that is invaluable in the early stages of writing, well before a story is ready to send to any editors. Writing in a community feels more real, engaging, and worthwhile.

Third Lantern Lit is a writing collective I co-founded, and the leadership team has grown to include many other New Orleans writers, who are doing an amazing job hosting free local meetups and events for the city. I’ve had people tell me our events are how they met the people who are now in their writing group, and that’s huge to me, because I know how radically a writing group has changed my own life!

New Orleans is home to some incredible writers, from established folks like Maurice Carlos Ruffin, Jami Attenberg, E.M. Tran and Katy Simpson Smith to debuting writers like Annell López, Vanessa Saunders, Danny Cherry Jr. and others. It’s a big enough community that it feels like there is always something going on, but also small enough that most people are connected and really cheer when someone gets great news or has a new book out.

JC: How has teaching at Tulane shaped your work? What do you include when you teach speculative fiction and design thinking?

MS: I co-teach a course at Tulane called “Speculative Fiction for Social Change” which is a labor of love. My co teachers, Sienna Abdulahad and Maille Faughnan, have exposed me to subgenres I hadn’t delved into before, like solarpunk and Black horror. One theme of our course is envisioning better worlds, not just dystopias, and thinking in that way has been a stretch for me, and is something I want to continue to explore. Reading student stories is endlessly inspiring.

When it comes to design thinking, I have lots of thoughts about how design thinking practices can inform writing practices: seeing drafts as prototypes to test ideas before marrying them, setting aside time for pure ideation (in addition to writing prose), not expecting a linear process of “improvement” but rather seeing the revision process as one of exploration. I believe that lowering the stakes is so essential in creative work, and that’s something design thinking emphasizes, and something I must remind myself of often. It’s part of why writing in new genres has been so freeing: I don’t expect to be good at it, so I just write!

JC: What are you working on now/next?

MS: I am working on a novel draft, Egret. It’s a historical and weird story about a spunky female journalist who discovers miracles and dark secrets while covering the 20th century Gulf Coast plume wars—when egrets were hunted almost to extinction for their prized feathers, and early conservationists started efforts to halt that. Right now I am deep in revision, in the middle of draft seven!

I’ve also been experimenting with short fiction across different genres. Some writing group mates and I have challenged ourselves to tackle murder mysteries, westerns, second-world fantasies, a solar punk story, and now we are trying romance. It’s been a great experience: so fun and invigorating. It’s like cross-training for a marathon, except in this case we are cross-training for novel-writing. It’s been so positive that Tierney Oberhammer and I are hoping to teach an online course for writers about playing in different genres in Spring 2025, with The Porch.

__________________________________

The Man in the Banana Trees by Marguerite Sheffer is available from University of Iowa Press.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.