Margot Livesey and What Literature Can Tell Us About The Future

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

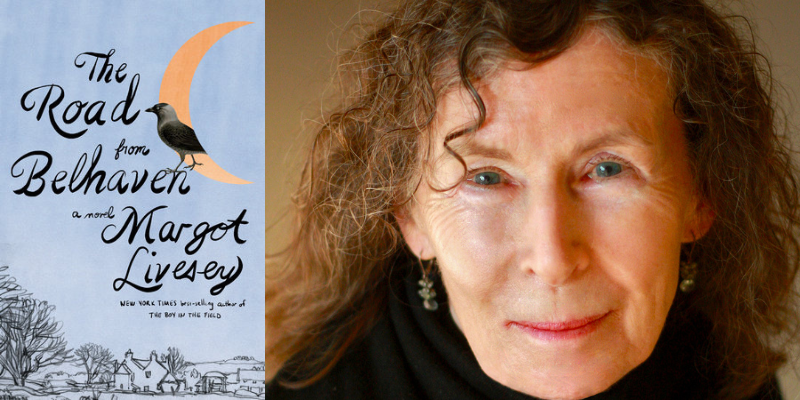

As the 2024 Presidential race heats up, award-winning fiction writer Margot Livesey joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss the value of seeing the future in politics and in family life. Are the polls right? Will Donald Trump beat President Joe Biden in the November election? Livesey talks about the role predictions play in our political landscape and in her new novel, The Road from Belhaven, in which a young woman named Lizzie Craig, raised by her grandparents in 19th century Scotland, has the gift of second sight. Livesey discusses the ways that literature has handled the concept of “seeing the future” over time, including the role second sight plays in Macbeth. She reads from her novel.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

V.V. Ganeshananthan: Can you talk a little bit about how Lizzie’s second sight plays out across The Road from Belhaven, avoiding any spoilers?

Margot Livesey: Because I mentioned heredity earlier, I should say that, sadly, so far, I have no gift of second sight. So, I set out to do research, and I interviewed a number of people who could see the future. They described what that was like. Not just what they saw but the feeling that accompanied those moments when they saw something, which I found incredibly interesting. Without exception, the people I talked to, like Lizzie, couldn’t choose what they saw. Often what they saw was quite ordinary like losing a mitten or, in Lizzie’s case, a neighbor wearing a new hat. But for Lizzie, there are some key moments where she sees really momentous things, and she tries to intervene. As you might expect, the results of trying to change the future are quite mixed. But in some ways, I think she eventually regained control of her future.

Whitney Terrell: It would be nice to imagine that we could all do that. I guess I would do the opposite of her sister, Kate. I would say if you see something about me—if I knew someone like that—I do not want to know anything at all about that. What would you do, Margot, if you were in that situation?

ML: I don’t think I have your willpower. I think I would say, “Bring it on, tell me what’s going to happen.” I think so. But who knows? So far I haven’t been tested.

WT: Given that The Road from Bellhaven is set in 19th century Scotland, precognition is kind of the only thing that’s happening in this book. The other thing that we were thinking about is how different the world that Lizzie is living in is, in terms of gender equality and the ways that relationships work, compared to contemporary Scotland. How did you think about those issues as you were thinking back into the past of this story?

ML: Well, it’s so easy to take the Victorian novel as the received picture of Victorian life. But in fact, research suggests that Victorian life, in many ways, differs dramatically from that portrayed and in the novels we cherish. The manners and morals were quite a bit different. So, I hope that what people will see when they read about Lizzie is some of the things that are still constant when you struggle to make good choices. At the same time, we’re uneasily aware of the significant role chance often plays in our lives.

We believe in reason and yet sometimes our feelings overwhelm reason. I think the lives of children are very passionate. I think it’s like acting out King Lear every day, being a child, but your children typically don’t understand the dark river of sex that underlies adult life and how that is acting like a magnet on people’s choices so often.

Then there is the world of work, and Lizzie very much inhabits the world of work, like most contemporary readers. I hope there’s a way of getting from the 2020s to the 1880s that doesn’t make the reader feel that they are entering a historical novel so much as stepping into a slightly different version of a life that could be being lived just down the road from them.

VVG: It does feel strikingly contemporary. So, I’m curious. There are some things that Lizzie sees pictures of, and then there are other key decisions, where she is not given any vision of what the future will look like, so she is actually making her decisions in the absence of knowledge. Then, there are other moments where other characters will predict the future for her, but they’re doing it in a way that just arises from common sense and a greater adult understanding of the world than the one she has.

When we start the book, she’s 10 and she’s a kid, and she sometimes sees things in general and in the way that a kid does. She sees a lot that she doesn’t always understand or know how to interpret. Early in the book, there’s a very sad moment where we understand that a young woman has died by suicide as a result of expecting a child and knowing that the father is not going to marry her. This is, in a way, a thing that links to the women later in the book and some of the choices that they face, don’t face, or want to face. But sometimes the predictions don’t arise from any magic, they just arise from adult knowledge.

I’m so curious about how you picked what Lizzie would see and not see because of course, you’re pulling the strings. So, how did you decide?

ML: One of the most difficult things to decide was what she would have pictures of and when the pictures would interrupt her daily life. Most of her life is very daily, it’s feeding the hens, milking the cows, churning the milk, going to school, and later going to her job. So, it was quite hard to decide how often the pictures should remind her of this force sort of hovering nearby, as it were. I like so much of what you said about the role of adult common sense in her life and how the adults around her suggest what might happen. Of course, she resists many of those suggestions, even the suggestions that come from Kate, who’s only a couple of years older.

WT: Adults, I mean, children too, can have precognition all the time. You can see two people get together in a relationship, and you can say, “That is not going to work.” I can see that, but they have to go through it themselves. It doesn’t do any good to tell them. Even if you end up being right, in the end, that’s part of the process.

ML: Sometimes that process takes decades. My dentist told me recently that one of his colleagues was getting divorced, at the age of 85, from his first marriage.

WT: Maybe he needed to go through all of that. I don’t know. If you told him, “At 85, you’re going to get divorced,” maybe he’d say, “Well, okay, that’s a nice long run.”

VVG: I love the fact that you’re going to the dentist and receiving amazing stories.

ML: Well, needless to say, I’m a helpless listener. So, the dentist just talks about whatever he chooses. But I do think that all of us want to feel we’re in control of our lives, and we’re more or less committed to the idea that we have free will. Then, as we grow up, various things begin to put pressure on that idea. The idea of heredity, the idea of family patterns, the idea of luck and coincidence playing a role, and in Lizzie’s case, the idea that the future is somehow already mapped out and just waiting for her to step into it.

VVG: When you discovered that this was something that your family was connected to, and then when you discovered it again, in the figure of Elizabeth Craig, did you feel relief? Dismay? Do you own a Ouija board or a Magic 8 Ball?

ML: I used to have a Magic 8 Ball that I consulted relentlessly. In fact, when I first was at Iowa with Whit, I often consulted the 8 Ball, and I have to say it was not a very good oracle. It was mostly ambiguous and misleading. And, of course, I’m like a diviner looking for water. I keep hoping that somehow I’ll have second sight, but I remain very rooted in the everyday.

WT: Except, you’ve written a novel in which you get to give visions to a person. So actually, you are creating second sight within the fictional world.

ML: I like to think so. And indeed, my main kind of second sight at the moment is actually rereading novels I love, which I’ve mostly forgotten, and then suddenly, as I’m reading I remember them.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Mikayla Vo.

*

The Road From Belhaven • The Boy in the Field • Homework • Eva Moves The Furniture • The Flight of Gemma Hardy

Others:

Daniel Deronda by George Eliot • Fiction/Non/Fiction: Season 3, Episode 24: “Summer Books Extravaganza: Margot Livesey and Jaswinder Bolina on Beach Reading When the Beach is Closed” • Fiction/Non/Fiction: Season 5, Episode 35: “Boris Johnson: Margot Livesey on British Politics, the Brexit Blunder, and the Prime Minister’s Lies” • No Great Mischief by Alistair MacLeod • The Thirty-Nine Steps by John Buchan • Till We Have Faces by C.S. Lewis • Macbeth by William Shakespeare • Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J.K. Rowling • Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon • L.M. Montgomery