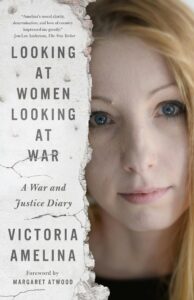

Margaret Atwood on Victoria Amelina, Who Recorded the Lives of Ukrainian Women Under War

Remembering an Award-Winning Writer Who Sacrificed Her Life For Justice

In the middle of a war, there is little past or future, little perspective, little accurate prediction: there is only the white heat of the moment, the immediacy of perception, the intensity of emotions, including anger, dismay, and fear. In her tragically unfinished book—written from the center of Russia’s appalling and brutal campaign to annihilate Ukraine—Victoria Amelina also records the surrealism: the sense that reality has been skewed as in a nightmare, that this cannot be happening. Bombed kindergartens, with Soviet cartoon characters smiling down from the walls.

But there are also moments of courage, of companionship, the shared dedication to a cause. In this war, Russia is fighting for greed—more territory, more material resources—but Ukraine is fighting for its life; not only its life as a country, but the lives of the citizens of that country, for there is little doubt about what the outcome of a Russian win would be for Ukrainians.

The massacres, the wholesale pillaging, the rapes, the summary executions, the starvation, the child stealing, and the purges do not need to be imagined, for they have happened before. Russians claim to be the “brothers” of Ukrainians, but Ukrainians reject the kinship. Who needs a “brother” who is a homicidal psychopath and is trying to kill you?

This is the context in which so many Ukrainian artists gave up their primary art to dedicate themselves to the defense of their country and their fellow citizens. Victoria Amelina was among them. Before the war, Victoria Amelina was a talented and well-known literary writer. She was, as we say, award-winning. She published novels and children’s books, traveled internationally, and started a literary festival. But all that changed when Ukraine was invaded. She turned to war reporting, researching war crimes for the Ukrainian organization Truth Hounds, interviewing witnesses and survivors.

Many religions have a figure that we may call the Recording Angel—the spirit whose job it is to write down the good and bad deeds of humans. These records are then used by a deity to achieve redress—to balance the scales that the goddess Justice is so often shown as carrying. War crimes are by definition bad deeds. Truth Hounds is a Recording Angel of the atrocities committed against Ukrainians. Amelina is looking not primarily at the war crimes as such, but at the stories of those women who, like her, are attempting to document those crimes, and also at the stories of women under siege: their ruined apartments, their attempts to evacuate, their killed partners, the shattered Lego constructions of their once-happy children. Her writing is hasty, urgent, up close and personal, detailed, and sensual.

Amelina is looking not primarily at the war crimes as such, but at the stories of those women who, like her, are attempting to document those crimes, and also at the stories of women under siege…

She follows in the honorable footsteps of earlier women war reporters such as Martha Gellhorn, who wrote, “It is necessary that I report on this war I do not feel there is any need to beg as a favour for the right to serve as the eyes for millions of people in America who are desperately in need of seeing, but cannot see for themselves.” Artists like Amelina help us to see, but also to feel. They serve as our eyes. Amelina’s talent as a novelist was of great service to her, and now it is of great service to us.

Amelina had put together about 60 percent of the book at the time of her death. Much of that material was in raw form—fragmentary, unpolished, unedited. As the editorial group putting the book together has said, “While the author managed to finalize the overall structure and write up some of the chapters . . . other sections remain unfinished. They are composed of unedited notes, reports from field trips with no context, or limited to just a title. The editorial group’s strategy is to minimize their intrusions into the original manuscript and, where such intrusions are impossible to avoid, make them explicit to the reader.” The resulting text is intensely modern. It reminds us of—for instance—the Pessoa of The Book of Disquiet and the Beckett of Krapp’s Last Tape. Incompleteness draws us in: we long to supply what is missing.

I have found it difficult to write this: How can you draw any conclusions, make any resounding statements, with the subject of the book still in flux?

War is not static but fluid. It moves, it destroys, it sweeps away everything in its path, it drowns many. Its outcomes and ripple effects are unpredictable.

This war was supposed to be a slam dunk—according to many pundits, it would only take a few days after the invasion in February 2022 to polish off Ukraine—but as I write this, it’s been over two years, and small Ukraine has retaken over half the territory seized by huge Russia at the beginning of the onslaught.

War is not static but fluid. It moves, it destroys, it sweeps away everything in its path, it drowns many. Its outcomes and ripple effects are unpredictable.

But as of right now—June 2024—the Russian attempt to take Kharkiv has ground to a standstill; Ukraine has just been told that French military personnel will now operate openly on the Ukrainian side; and the United States has given Ukraine the green light to strike military targets inside Russia, which should impede the cascade of Russian missiles of the kind that just destroyed a deliberately targeted civilian shopping center; and that hit a Kramatorsk restaurant in the summer of 2023, killing Victoria Amelina at the age of thirty-seven.

This is her voice: fresh, alive, vivid, speaking to us now.

______________________________________

From Margaret Atwood’s introduction to Victoria Amelina’s Looking at Women, Looking at War. Read an excerpt from Looking at Women, Looking at War here.

Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood, whose work has been published in more than forty-five countries, is the author of more than fifty books of fiction, poetry, critical essays, and graphic novels. In addition to The Handmaid’s Tale, now an award-winning TV series, her novels include Cat’s Eye, short-listed for the 1989 Booker Prize; Alias Grace, which won the Giller Prize in Canada and the Premio Mondello in Italy; The Blind Assassin, winner of the 2000 Booker Prize; The MaddAddam Trilogy; The Heart Goes Last; and Hag-Seed. She is the recipient of numerous awards, including the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade, the Franz Kafka International Literary Prize, the PEN Center USA Lifetime Achievement Award, and the Los Angeles Times Innovator’s Award. In 2019 she was made a member of the Order of the Companions of Honour in Great Britain for services to literature and her novel The Testaments won the Booker Prize and was longlisted for The Giller Prize. She lives in Toronto.