Making Sense of Middle Earth: Exploring the World of J.R.R. Tolkien

Michael D.C. Drout Remembers the Impact of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit on His Childhood

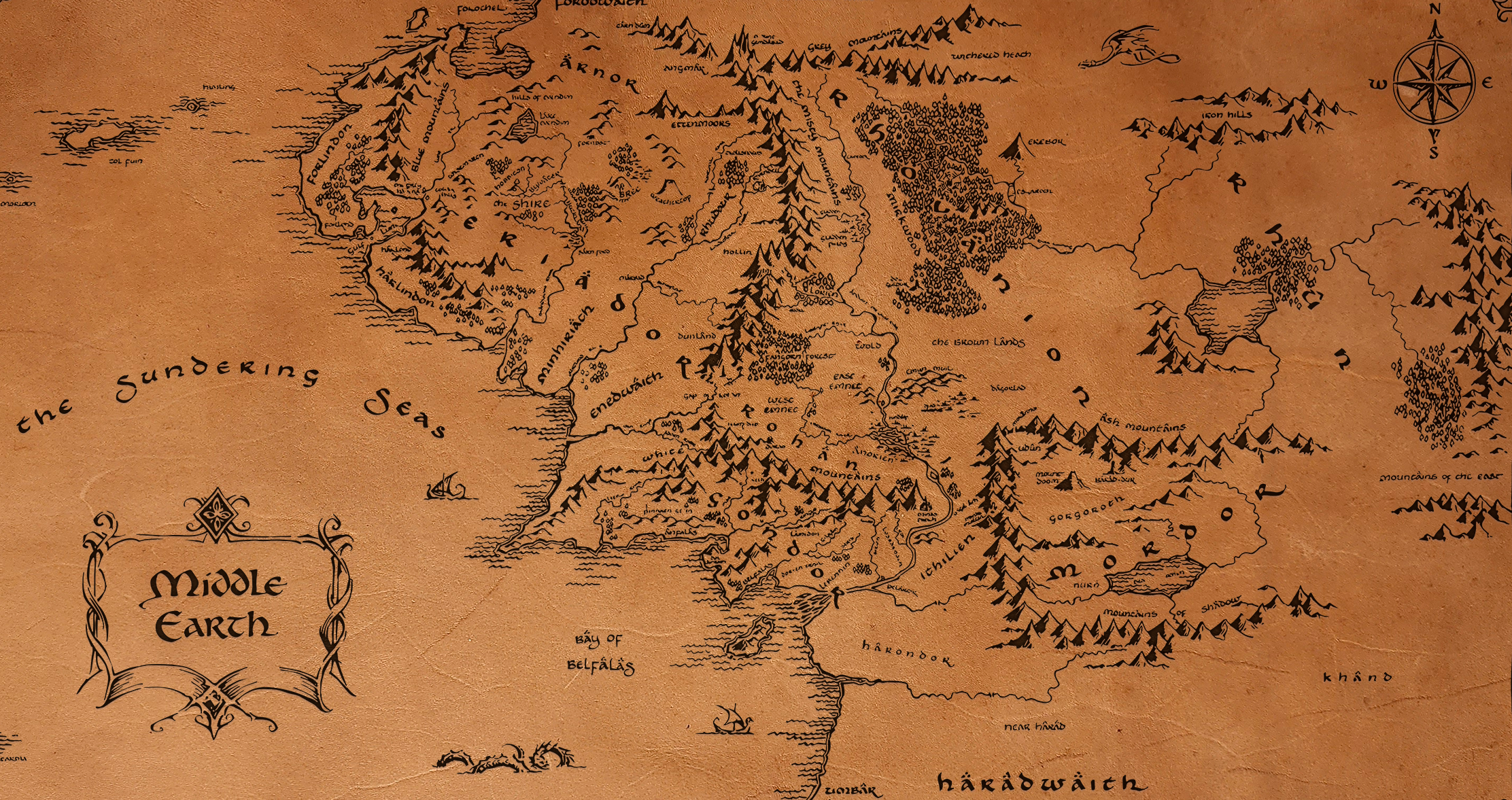

My first interest in J.R.R. Tolkien was apparently caused by the infamous Barbara Remington artwork used for the covers of the Ballantine mass-market editions. When my father bought his paperback copies of The Lord of the Rings at the Cornell University bookstore in 1969, the three volumes came with a free poster of the Map of Middle-earth, also illustrated by Remington. That map somehow ended up taped on the wall of the spare room in my grandmother’s house. According to family lore, one day I stood up in my crib, pointed to the “Black Riders” at the bottom of the picture, and kept repeating “What that? What that?”

I had to wait a few years for an explanation. But although I now know what a Black Rider is, to this day I do not understand what the three salamanders riding on a flattened frog, the pointed-nosed lizard-thing leaping from the water, the lion-maned dragon-snake, or the angry dog-monster have to do with The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien was also confused, although he seemed more exercised by the emus and the tree with bulbous pink fruit on the covers of The Hobbit and The Fellowship of the Ring.

For me, engaging with Tolkien’s work began with trying—and failing—to figure things out, to synthesize fragmented, disjointed, and contradictory material into some coherent whole. That sounds like an inauspicious beginning to either a lifetime of loving Tolkien’s work or a career as a literary historian, but in fact it is the same experience—although perhaps with a bit less failing—that every first-time reader of The Hobbit has when trying to make sense of something called a “hobbit” whose mother was “the famous Belladonna Took,” an experience that recurs throughout the course of reading The Hobbit and is even more common in The Lord of the Rings.

Engaging with Tolkien’s work began with trying—and failing—to figure things out, to synthesize fragmented, disjointed, and contradictory material into some coherent whole.

One of the central claims of this book is that the mental effects of the small gaps, contradictions, and inconsistencies in Tolkien’s work contribute substantially to readers’ experiencing it as somehow different than other pieces of literature. I will also argue, however, that this was not originally Tolkien’s conscious intention but rather arose out of the long and tortuous composition-history of Tolkien’s works. I do not intend in any way to disparage Tolkien’s genius—a word I use in the most old-fashioned, naïve, unironic sense possible—as both writer and scholar, and I will not be focused on nitpicking apparent “flaws.” Instead, my intention is to show both what Tolkien did and how he did it.

We will be examining what Tolkien called “the course of actual composition,” and I will not pass up noting that, at times, he worked his way from what is, in retrospect, a terrible concept (the Ring is “not very dangerous, if used for a good purpose”), or name (Teleporno was the king of the elves of Lothlórien; Frodo was Bingo Bolger-Baggins), or plot-point (Bilbo stabbing the dragon “with his little knife”), to what became a great work of literature that has the power to engage an immense range of readers, engage them more deeply, and, most importantly, engage them in fundamentally different ways than its predecessors, contemporaries, or imitators. This last point is far more important to me than the others. Trying to explain popularity is an exercise in sociology or marketing and therefore, in my view, a waste of the literary historian’s time.

But trying to explain what about Tolkien’s books may lead people to treat them differently than other texts is another story. The Lord of the Rings is over 600,000 words long; it contains many poems in various forms; it uses hundreds of unfamiliar names; there are untranslated passages written in invented languages; and the book depicts multiple scenes of terror and violence, including the mutilation of the protagonist—of course we should read it out loud to our six-year-old… and people do.

*

The first actual memory I have of anything related to Tolkien is my father reading “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit” while I struggled to stay awake in our stuffy and always overheated New York apartment on the ninth floor of 435 East 70th Street, one of our cats curled up at the foot of my bed, and my younger brother, a toddler, already asleep in his crib a few feet away. It was therefore late 1973 or early 1974, and I was five and a half years old. For the next two years, at bedtime my father would read me The Hobbit, then The Lord of the Rings, and when we reached the end of The Return of the King, we would go back to the beginning of The Hobbit. Often my father would start to doze while he read, so his voice would slur a bit and his New Jersey accent would become more pronounced. Half a century later, when reading the books silently, I sometimes hear his voice and his mispronunciations, /Le-gÓ-las/, /SAR-on/, /THEE-o-den/.

Feelings of comfort and happiness accompany these memories, but there is also sadness and stress and, in retrospect, a foreboding darkness. My father was completing his internship and residency at New York Hospital at a time when physician-training hours had not yet been scaled back to humane levels. He worked not only every day, but also every other night for weeks at a time, so his being home when both he and I were awake felt like a special privilege. There was also illness and fear: My brother and I both struggled with asthma exacerbated by the tight quarters, two pet cats, every adult smoking, and a building infested with cockroaches. The asthma attacks and occasional pneumonia were exhausting, and worse, frightening, because my father, a figure of calm mastery whenever we saw him at the hospital, could not hide the worry on his face when either of us was sick.

There was also some darkness around the edges of our lives, although I was too young to name it. Poverty, even the temporary poverty of medical school and internship, is hard for any family; there were also familial and marital tensions that I sensed even if I did not understand; and the city around us could be harsh and frightening. Sometimes we heard gunshots at night, and one day, in Carl Schurz Park, my friend and I found a man lying unmoving inside the spiral slide in the playground. As she hustled us away, my friend’s mother said the man was sleeping, but I had seen that his eyes were open. A similar kind of darkness sometimes shadowed The Hobbit, beginning with Bilbo’s inexplicable (to five-year-old me) panic at the thought of a dragon coming to the Shire and continuing with the hushed mentions of the Necromancer, the glimpses of the ruined castles on the journey to Rivendell, the laments of the Lake-men for their burned homes—hints of far more deep and serious fears that felt distinctly different from the scary excitement of the trolls, goblins, wargs, and the Spiders of Mirkwood.

What might have been just an engaging children’s story becomes also a set of hints, allusions, and glimpses, the early experiences of learning about a larger world.

The Hobbit and its literary effects are thus for me inextricably tangled up with early memories from a time when much was confused. Or, perhaps more accurately, particular qualities of The Hobbit entered deeply and permanently into my psyche, entwined with memories of warmth and safety, of being comforted and protected, and also with flashes of terror: of struggling with all my strength to draw in one breath and then starting the struggle again for the next one; of watching my brother’s lips turn blue and my father suddenly sweep him into his arms and dash out to the emergency room; of overhearing whispered, frightened conversations with words that I did not understand but knew to fear: arterial blood gasses, cystic fibrosis, intubate.

These circumstances could perhaps account for the vividness of my memories of those first glimpses of Middle-earth: Fever and illness can intensify perceptions; minor traumas can fix memories; and there may also be some echo of Tolkien’s own severe illnesses in the rhythms of the narrative—more than once Frodo’s pain and suffering leads to clouded vision, exhaustion, and eventual unconsciousness, followed by a peaceful awakening under clean sheets with the morning sun pouring through a window. But why is it, then, that The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings—and not the many other books my father or mother read to me in that same period—have shaped my perception of my own life and the lives of my children? More importantly, why do so many other readers, in utterly different situations, have similar experiences with Tolkien’s work? Dumb luck might explain me—perhaps I encountered Tolkien’s work at just the right stage of intellectual development—but all of those other readers, too? Impossible.

Another explanation could be simply the high quality of the work: It is a well-crafted story written in an engaging style. But even taken together, these reasons are insufficient. Many different books must end up being read at just the right age (whatever that is) out of the millions of children being read to by their caregivers, and although Tolkien’s writing is of high quality (indeed, higher than was acknowledged by many critics for several decades), it is not transcendently superior to that of every other writer.

No one thing makes The Hobbit different from the other children’s literature of the same time period. A constellation of qualities combine to make the book produce its unique effects, and perhaps the only one that is utterly unique is that it is followed by The Lord of the Rings. The experience of reading that great work changes the reader and, in so doing, retrospectively reshapes The Hobbit. What might have been just an engaging children’s story becomes also a set of hints, allusions, and glimpses, the early experiences of learning about a larger world, the first steps in the process of creating a reader of The Lord of the Rings. And that reader, over the course of The Lord of the Rings, has learned along with and in the same ways as the viewpoint characters as they discover more of their world, actively synthesizing scraps of information into an ever-richer and more complete model, coming to understand Middle-earth in the same way we come to understand our world—by figuring it out on our own.

________________________

From The Tower and the Ruin: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Creation by Michael D.C. Drout. Copyright © 2025. Available from W.W. Norton & Company.

Michael D.C. Drout

Michael D.C. Drout is a professor of English and director of the Center for the Study of the Medieval at Wheaton College. He specializes in Anglo-Saxon and medieval literature, science fiction and fantasy, especially the works of J.R.R. Tolkien and Ursula K. Le Guin, and is the author of How Tradition Works and Drout’s Quick and Easy Old English, among others. He lives in Dedham, Massachusetts.