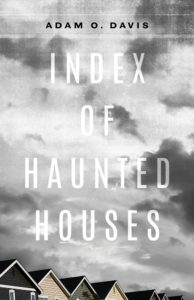

Making Poems into Phantoms, One Broken Line at a Time

Adam O. Davis Finds Ghostly Relics in His New Collection

In 2000, my family moved to Riverside, California. Upon arriving in the Inland Empire, we first lived in a motel wedged in the intersection of I-10 and I-15, then in a rented house whose dark wood-paneled walls and sunken living room whispered of a past filled with key parties and Teacher’s scotch, and then finally in a new home in a neighborhood whose streets had no sidewalks and whose houses seemingly held no people.

We never met the neighbors. We never saw the neighbors. The neighbors had Toyotas and Acuras that appeared and disappeared overnight in their driveways. They had trash and recycling cans that wheeled themselves autonomously into and out of the street on garbage day. They sometimes had strange backyard parties full of strange music and flashing lights but we never saw a single person at them. The only person I ever saw in that neighborhood was an elderly man who walked with a golf club, presumably to ward off the coyotes who yipped maniacally in the distance at dusk.

The wisdom in all this is that ghosts—and the hauntings they offer—can’t exist without opportunity. And by opportunity, I mean space. Ghosts need sizable real estate if we’re expecting them to haunt us effectively. A ghost town, for example, is far more powerful in its capacity for eerie wonder than a ghost gazebo. The abandoned town’s scale sets the imagination alight, while the abandoned gazebo inspires an HOA complaint—unless, of course, the gazebo in question stands in the middle of a vast, uninhabited desert. But in this instance we still need space.

The other critical component for a ghost and/or haunting (they aren’t mutually inclusive, you know) is specificity (or, as I like to refer to it when addressing my students’ poems, concrete). For something to be other than what it is, you first need that something to be what it is. And then, of course, something has to happen to it. It needs to be othered, alchemized by life into another life. This is how a ghost is born—and a ghost is not a vague, evaporative smattering of ethers; it’s just as rich and material as the thing it once was.

Ghosts operate the same way as language operates—a particular sound is echoed again and again in many mouths until it attaches itself to meaning.Think of a rotary dial telephone sitting on an empty table in a bare room. Its glossy black carapace catching the light thrown from the door you just opened. The telephone itself silent as a bomb, congenitally haunted by its potential to deliver unto you all kinds of news and voices. It knows you know what it can do. But it also knows that you don’t know what that is yet. Neither does it. This is what makes for a haunting. And this is what makes the telephone a ghost, the person calling a ghost, and, in some ways, you a ghost too.

This is also what makes for a good poem.

Ghosts operate the same way as language operates—a particular sound is echoed again and again in many mouths until it attaches itself to meaning and becomes a word like me or you or money. The echo is a plagiarism, but an essential one because the echo broadcasts the word even as it others it. Soon, the word has become several ghosts of itself.

And what of those ghosts? They unfurl in a phantasmagoric fractal through our waking and unwaking lives, infusing our day-to-day conversations with the danger of a dead man’s curve—a misplaced letter, a transposed or dropped syllable, and suddenly we might be thrown into an entirely different understanding of reality. Don’t believe me? Try to think of light or proper spelling in the same way after reading Aram Saroyan’s “lighght.”

The fun of poetry and the job of the poet is to echo the echo, to further corrosion, to court all manners of linguistic erosion and add-ons until they render language as pointed and raw as split wood. At its root, language is a well-metered music. Mutable, playful, full of pith and vinegar depending on the mood, the context, the speaker, the writer. Every word is a lycanthrope whose behavior depends entirely upon the moon you meet it under. And this kind of supernatural threat is exactly what I want out of poetry—the shapeshifting agency of lyric language that can turn on the reader (and, with luck, the writer) at will. Ain’t that just like a werewolf to go wolfish right when the date was going so well?

In the case of my book Index of Haunted Houses, I had to other the poems and in doing so other myself from them (read two of them here). I had to abandon what I had so that new ghosts could help make the book what it needed to be and not what I had wanted it to be.

*

Back in Riverside, there was no other word for the neighborhood my family lived in but eerie. And Riverside itself, built on the grave of a colossal orange grove, was just as eerie. The city felt both overdeveloped and undiscovered. Apartment complexes and strip malls bloomed like mushrooms between agricultural stations and empty lots. Inflatable figures danced wildly in front of new supermarkets, new hookah bars, new restaurants, but no matter where you went things felt forsaken.

Businesses would open only to close and, as if ignoring the ghosts of the previous tenants’ ventures, new businesses would open in the same places only to close again. There was the feeling of commercial retrofitting everywhere: the bank turned Krispy Kreme turned bank again; the Pizza Hut turned Thai restaurant. With a friend I’d visit the Riverside Plaza mall, wandering past its lengthy stanzas of shrouded stores as elderly speed-walkers made circuits around us in the air-conditioned cool.

Most cities are prosaic, their pages so packed with text that you can’t tell what was there before, meaning that its ghosts have no space to haunt you. But Riverside was a blank page with a few careful words printed on it, and nowhere was that absence more pronounced than the old March Air Force Base housing development on the west side of the I-215. In the 1980s, residents there started to suffer lead poisoning. Within a decade the entire neighborhood was abandoned. Like some forbidden city of the nuclear age, the whole place wasn’t so much forgotten as it was ignored, as if by acknowledging its toxicity you’d encourage its power.

Back in the early 2000s, there was nothing to stop you from entering that abandoned neighborhood (it has since been replaced with a Sysco warehouse and another housing development). No signs warned you against entering it and no barricades blocked you from driving those weed-split streets. In overgrown backyards, swingsets creaked in the wind. If the houses still had their front doors, they went unlocked.

Dusty venetian blinds chattered against broken window frames. In bathroom medicine cabinets you might find old pills, razors, toothbrushes. Some bedrooms still had beds in them beside which used condoms curled on the beige carpet like molted lizard skins. Spiders constructed cloudy nests in the lamp sockets of ceiling fans—the light bulbs being the one thing that were always missing.

Walking through those houses was like trespassing on people’s lives, like being a tourist to tragedy. Which is, I think, what it must feel like to be a ghost. So a ghost is what I felt like in those houses and in those yards. A ghost floating through a small-scale Pompeii within view of a freeway. At the neighborhood’s southern edge there was a swimming pool filled with dirt. The diving board still bolted in place over it, daring you to jump.

In The Weird and the Eerie, Mark Fisher writes, “Confronted with Easter Island or Stonehenge, it is hard not to speculate what the relics of our culture will look like when the semiotic systems in which they are embedded have fallen away.” That abandoned neighborhood wasn’t so far removed from our culture that it was simply a series of obelisk-shaped ciphers, but it still contained within it the core mysteries of the American progress, those stories about what was before and what no longer is.

Stories like those of the Anasazi or the citizens of Chavez Ravine. The vanished, the fled, the forcibly evicted. History masquerading as ghost stories. But what is history if not a ghost story?

And it was this history, by way of ghosts, that I wanted to explore in Index of Haunted Houses. I began to understand my collection as an echo chamber where sounds would collude and collide with each other in a book-length game of Telephone until certain poems, like certain histories, would melt under the force of repetition. But to give the book the kind of kaleidoscopic echoing (aka haunting) it needed, I had to other what I’d been working on. And to do that, I had to burn what I had to the ground.

Having worked on the manuscript for seven years (by the time it won the Kathryn A. Morton Prize at Sarabande Books, I’d spent thirteen years working on it, and ten of those submitting it), I had seven years’ worth of reasons to leave everything as it was. I was like the bad luck gambler who keeps his perch at the blackjack table despite his losses, reasoning that if he’s spent so much money to dig himself so deep into debt he might as well spend a little more on the slim chance he could dig himself out of it. It’s the most rational bit of irrationality you can imagine.

What I had were relics and it was my job to listen to them, to hear what they needed. And, soon enough, the poems became new to me.Eventually, I accepted what I had to do. And the only way I could justify doing so was by putting my faith in the language. For me, this meant trusting that my work would be made richer by being othered. I had to burn everything I’d done to the ground to see what would remain. I had to forget about being a wrangler of language in favor of being a conduit—no longer a linguistic cop but a semantic lightning rod. I had to give myself—and, more importantly, the poems—the opportunity to be surprised.

Much of this process involved breaking poems—many of which I loved and had been published by journals of repute—into pieces. I bid countless stanzas adieu, sacrificed some of my favorite lines (though now, for some reason, I can no longer remember what they were), and blew open the poems as if they were jewel safes. In many cases, the forms found in the book are denotative of their demolition—some poems still zippered in tidy couplets while others are strewn like shrapnel across the page.

During this “quarry work,” as I called it, I felt as if I was now fleeing one of those forbidden cities of the nuclear age, given only minutes to pack and so only the essentials would do. What I had were relics and it was my job to listen to them, to hear what they needed. And, soon enough, the poems became new to me, strange and beguiling, the whole manuscript an homage to the abandoned, forgotten, misplaced landscapes of my youth and full of historical markers so explicit that they defied time.

Sure, there were many times during that reconstruction that I wondered if I’d broken what was, if I shouldn’t go back and beg forgiveness from my former manuscript, but such conservative choices are always the enemy of progress and art. Never ask for reform when only revolution will do.

This past May, I received the first printed copies of Index of Haunted Houses. After slicing the packaging tape open with a house key I held my book for the first time. I hardly recognized it. I felt as if I was holding a gift I’d sent myself 13 years earlier. I opened the book and what I found was an overwhelming sense of space, the eerie sense of possibility and danger that, as a child of the American West, I know well—an eeriness that depends on space and all the longing and wonder and terror such space inspires.

The book was of me but no longer mine. It was its own neighborhood, abandoned but not empty, full of its own ghosts and weed-split streets and unlocked houses and dirt-filled pools. A neighborhood open to any who might want to enter it and wonder at what had been and what might otherwise be.

__________________________________

Adam O. Davis’ poetry collection Index of Haunted Houses is available now.