Maggie Smith on How to Revise Poems Without Losing the Initial Spark

“If a poem is a machine made of words, it only runs as well as the words we choose to build it.”

Revision is my favorite part of the writing process. I relish the creative problem-solving more than the rush of getting it down. If you’re like me, your poem might go through anywhere from two to two hundred drafts before you’re satisfied enough with it to call it “done” and send it out. Each revision, ideally, gets us closer to the poem we sense is there, waiting. The poem that will do the psychic or spiritual work we want it to do.

But each revision can also pull us farther away from the initial spark of the poem. This tension, this push and pull, is what makes revision dynamic and exciting: we are hunting something but are not quite clear about what it looks like or how to find it.

My poems almost always begin as scraps of language scrawled in a notebook or on a legal pad. If I’m lucky, one image or metaphor will lead to another, and before I know it, the draft is picking up speed down the page, gathering momentum as I try to keep up and see what it’s doing. I never learned to properly type, so I try not to put my two index fingers to work until I’ve done all I can longhand and need to see the shape of the thing on screen.

“At the End of Our Marriage, in the Backyard” must have begun on a legal pad, because I flipped through my past two writing notebooks, and while I found the starts of many poems I recognized, I did not see any images or lines from this one. No scrawled milkweed feathers or crumbs of pollen.

Here is the poem as it first appeared in American Poetry Review, and as it appears in Goldenrod:

At the End of Our Marriage, in the Backyard

We let the lawn go to wild violets and dandelions,

to crabgrass, to clover bending under the weight

of so many honeybees, our children can’t run

barefoot. We do nothing, letting ivy snarl

around the downspouts and air conditioner,

letting milkweed grow and float its white feathers.

We do nothing and call it something—as if

this wilding were intentional. If there is honey,

I tell myself, we are to thank. All summer

the children must wear shoes. We sit out back

while they crouch in the clover, watching the bees,

calling out when they see sunny crumbs of pollen

on their legs. Maybe no one will be stung.

Late in the season, we sit ankle-deep

in weeds and flowers. In weeds we call flowers.

If you know my poems, you know I love being outside. My work is full of descriptions of clouds, birds, trees, flowers, insects, squirrels—my surroundings here in central Ohio. But if you know me off the page, you have probably heard me joke about wanting to pave my entire back yard. Just black-top the whole damn thing! No mowing! No weeding!

In “At the End of Our Marriage, in the Backyard,” letting the yard go means the bees and butterflies are happy, but the children cannot safely play barefoot. Complacency has a cost. Sometimes people are stung.

Each revision, ideally, gets us closer to the poem we sense is there, waiting.

When I looked back through my Word documents, I found an earlier draft of the poem:

We let the lawn go to wild violets and dandelions,

to crabgrass, to clover bending under the weight

of so many honeybees, our children can’t run

barefoot. We do nothing, letting ivy snarl

around the downspouts and rusting air

conditioner, letting milkweed grow and float

its white feathers. We do nothing and call it

something—as if this wilding were intentional.

If there is honey, I tell myself, we are to thank.

All summer the children must wear shoes.

They crouch in the clover, watching the bees,

calling out when they see sunny crumbs

of pollen on their legs. Maybe no one

will be stung. Together we sit ankle-deep

in weeds and flowers. In weeds we call flowers.

I was startled to see how similar the drafts are. Many poems of mine undergo radical changes in revision: shifts in verb tense of perspective, a re-sequencing of imagery and ideas, a completely different closing. But it seems this draft knew what it wanted to do fairly early on. It was already in couplets at this point, and the general sequence of ideas is the same.

When I am tinkering with a draft, I experiment with different word choices based on sound and connotation. I liked snarl for the hardness of it, and the suggestion of both entanglement and a near-growl. I liked “wild violets and dandelions” together for the long I assonance and S sounds; I paired crabgrass and clover for the hard C alliteration. I tend to be wary of alliteration, which can feel too “light” in a poem if we’re not careful, but it’s subtle here because the words begin with consonant blends—cr and cl—and also because the alliteration is interrupted, softened, by the comma and the word to. I chose “grow and float” for the long O assonance, and “sunny crumbs” (as opposed to “yellow crumbs,” or “golden bits,” or any other pairing) for the short U.

I am looking and listening for consonants and vowels as I draft, but also the rhythms of sentences. I play with length and structure for pacing and emphasis. I might hit the brakes in a poem by following a few longer, more ornate sentences with a short, plainly stated one, or I might shift from statements to a question, or vice-versa. So much of the power in a poem is in making and breaking the reader’s expectations. We hear a shift and pay closer attention. “Maybe no one will be stung” is a moment like that.

As you can see, most of the changes between this earlier draft and the final version are related to line breaks. “Maybe no one will be stung” was, in this earlier draft, broken across lines: “Maybe no one / will be stung.” In this draft, “If there is honey, / I tell myself, we are to thank. All summer / the children must wear shoes” was stated more matter-of-factly in two end-stopped lines, each neatly containing its own sentence:

If there is honey, I tell myself, we are to thank.

All summer the children must wear shoes.

Why the shift? For one, “air conditioner” was modified in the earlier draft: rusty air conditioner. It’s accurate—that old behemoth is 30-some years old and still working—but I decided that rhythmically I didn’t like an adjective there. I didn’t think it was really doing anything. When in doubt with adjectives and adverbs: remove them. Also, I knew I wanted a fairly even line length in the poem, so removing rusty left a hole in that line and allowed me to bump up conditioner. That had a domino effect, so I shifted words and phrases in subsequent lines to fill subsequent holes.

I am looking and listening for consonants and vowels as I draft, but also the rhythms of sentences.

The two other changes from the earlier draft to the final version have to do with how—and where—I insert the speaker. In the earlier draft, we move straight from the children having to wear shoes to the image of them crouching in the clover—the parents are not mentioned there. In the final version, the parents are re-introduced in the transition; the children are calling out to their parents.

In the last move, I swapped “Late in the season” for “Together.” The togetherness is implied by we, so it wasn’t doing enough work to justify its inclusion. But the idea of this scene taking place at the end of summer echoes the end of the marriage referenced in the title. I found that echo satisfying.

I tell my students that when we revise, we should take nothing for granted. The first draft of a poem is almost always the not-right words in the not-right order. I think of finding the right order as a “macro,” big-picture act of revision: Where might the poem begin? Where might it end? What is essential, and what can fall away? What are the other possibilities? Finding the right words is one of the “micro” acts of revision. Not “micro” because it is insignificant; it is everything. If a poem is a machine made of words, it only runs as well as the words we choose to build it.

______________________

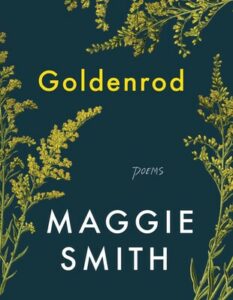

Goldenrod is available from published by One Signal/Atria Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2021 by Maggie Smith.

Maggie Smith

Maggie Smith is the award-winning New York Times bestselling author of eight books of poetry and prose, including You Could Make This Place Beautiful, Good Bones, Goldenrod, Keep Moving, and My Thoughts Have Wings. A 2011 recipient of a Creative Writing Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, Smith has also received a Pushcart Prize, and numerous grants and awards from the Academy of American Poets, the Sustainable Arts Foundation, the Ohio Arts Council, the Greater Columbus Arts Council, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She has been widely published, appearing in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, The Nation, The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Best American Poetry, and more. You can follow her on social media @MaggieSmithPoet.