Maggie Shipstead on Dealing with Mistakes in Writing

“Mistakes might be inevitable, but I think they are worth mitigating.”

The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s The Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

*

Maybe five years ago I read a novel in which a man drowns in a lake, and, a few minutes later, his body is found floating on the water’s surface.

If any of my writer friends are reading this, they’re probably groaning because they’ve heard me harp on this example before. What can I say? Sometimes I’m irritating and pedantic. But here’s the thing: it doesn’t make any sense for that body to float. If bodies were inherently buoyant, no one would ever drown. For that scenario to work, the man’s lungs would have filled with water, pulling him under and killing him, and then, almost immediately, something — the condition of death? — would have sent his body rocketing back up to the surface, where, despite being heavier now than before, he floated. No. Bodies float because gases of decomposition eventually lift them. The process takes time: at least a couple days even in relatively warm, shallow water, longer in colder, deeper water. Many bodies never surface at all. But the image of the floating body is pervasive in our culture and our entertainment (“We’ve got a floater,” says one TV cop to another), so familiar that a writer may skip directly from drowning to floating without stopping to think.

Not everyone will notice the lapse in logic, the accidental break from realism. In fact, most readers probably won’t question a floating corpse. People have vastly different levels of incidental knowledge and vastly different levels of critical engagement. John Gardner famously wrote that fiction should be a “vivid, continuous dream,” but some readers’ willingness to dream is more robust than others. Some people will shut a book forever at the first sign of an error, their trust in the writer and their suspension of disbelief irrevocably lost. Others will happily read along through almost anything, swallowing the most preposterous plot points, the most egregious anachronisms, and the most glaring inconsistencies. There’s an argument out there that factual errors don’t — or shouldn’t — really matter, that the artistic intention of fiction is what matters. Sure, okay, I guess, sometimes. But I think sloppiness is worth trying to avoid, both out of pure principle (why get something wrong when you could get it right?) and because mistakes can be indicative of an author not pressing hard enough on the world she’s building, not making it sturdy enough, settling for a facade. Mistakes, as in the example of the floating corpse, are frequently the product of cliché or wishfulness. They reveal that the author doesn’t know what he doesn’t know, that he’s basically just bullshitting.

It’s so easy to make mistakes in fiction. I’m certainly not immune. Once, at a pre-pandemic wedding, a friend’s father approached me and told me he’d enjoyed my first novel, Seating Arrangements. Then, in the next breath and with a triumphant smile, he informed me that I’d made a mistake. I’d described a certain prep school as using the term “forms” for the different class years, when, actually, that school didn’t. This was annoying on a few levels. First, it seemed petty that this small error (a single word!) was the first thing he mentioned to me about the book, and it was obvious from the way he’d bustled over that he’d been eagerly awaiting his opportunity. It’s not like I could do anything about the mistake, either. The book had been in paperback for years. The only point of his telling me had nothing to do with being helpful. He seemed almost gloating, like this one misused word had given him back some power over me, a young, female outsider who’d dared write about a man not so different from himself. Unlike him, I hadn’t come from a WASPy background, but Seating Arrangements contained critiques of how the cloistered high WASP world with all its secret codes, both material and abstract, fomented entitlement. My error revealed me as an impostor and undermined the book. Mostly, I was angry at myself. Why hadn’t I double checked? Why had I given someone — anyone — this kind of ammunition?

My second novel, Astonish Me, is about ballet (I’m not a dancer), and my third, Great Circle, is about aviation (I’m not a pilot). Great Circle, especially, was a research nightmare. The bulk of it is historical, and it takes place in roughly a bajillion different settings. (Okay, not really a bajillion.) As I wrote, I was continuously frustrated by how often I had to stop and look things up. Sometimes the most mundane questions — when would a house in Missoula, Montana, have gotten electricity and indoor plumbing? — were the hardest to answer. But the tiny, obscure technical questions were pains in the butt, too. Aviation, as a subject, seemed like an irresistible pedant magnet. I was haunted by the specter of the readers, usually men, who come to book events seemingly for the express purpose of standing up and offering corrections, having their know-it-all moment in the sun.

Even though your fiction might be, technically, all a lie, it’s not bullshit.

What could I do to preempt these actuallys, these “just pointing out”s? Only try my very best, really. I wrote in a constant state of uncertainty, pushing forward through a relentless onslaught of questions. I leaned into my ignorance, labored to be as meticulous as possible. Does that bird exist in that place at that time of year? Would that phrase have been in general use in 1928? Where in New York would an affluent family live in the 1890s? How is an ocean liner launched? How does an ocean liner sink? How do I contrive to make it feasible for someone to fly across Antarctica in 1950? I still made mistakes. My copy editor found plenty; my proof readers found more. Some snuck into the finished book, I’m sure. One gentleman emailed my agent a while ago to pass along some extremely quibbly notes, which I read, cringing in shame, until I got to the part where he started explaining to me what ice looks like. Sir, I’ve been to Antarctica twice, the Arctic five times. I’ve stood on the Greenland ice sheet, flown low over sea ice in the Northwest Passage. I don’t know everything, but I know ice. I deleted the email.

Mistakes might be inevitable, but I think they are worth mitigating, pursuing, ferreting out. If you can get rid of even just the biggest and most obvious ones, you will have made the dream of your fiction more vivid and more continuous. In the process of considering and reconsidering everything you’re writing down, by stopping to think, by tapping every wall and jumping on every floor, you will undergird your fiction with an intangible, pervasive trustworthiness that readers will sense, even if they aren’t always able to identify it. They’ll know that, even though your fiction might be, technically, all a lie, it’s not bullshit.

__________________________________

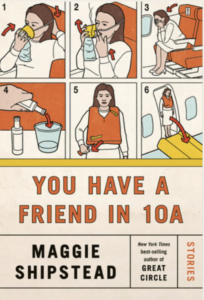

You Have a Friend in 10A: Stories by Maggie Shipstead is available via Knopf.

Maggie Shipstead

Maggie Shipstead is the New York Times best-selling author of the novels Great Circle, Astonish Me, and Seating Arrangements and the winner of the Dylan Thomas Prize and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for first fiction. She is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, a former Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford, and the recipient of a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. She lives in Los Angeles. Her first collection of short stories, You Have a Friend in 10A, is out now from Knopf.