As a child, I loved a eucalyptus tree at the end of our garden. I mean, I truly loved it. I would admire its silvery jigsaw-patterned bark and climb its branches with my sisters to use its gray-green leaves as a hideout. Eucalyptus trees are not common in Ireland, and this one felt like a real and exotic presence within my family, with its menthol smell and great height. I forgot all about that tree until shortly after Donald Trump was elected president, and I was rushing to catch the train and heard a rustling from one of the trees that line the sidewalk in Brooklyn.

When I glanced over, I realized it was a woman softly embracing a sycamore. Her hands didn’t quite meet on the other side, but she was melted onto the tree and her eyes were closed in mid-cuddle. I looked away quickly, because it felt like a private moment. I had an urge to laugh. Little did I know that in a few short weeks I too would make a habit of sidling up to a sturdy maple and giving it a quick squeeze before running to catch the F train.

Although it was winter and the branches were bare, hugging that tree still felt good. No matter the season, a tree’s trunk is solid, the bark rough and reliable. I was self-conscious at first; still am, a little. I try to make sure nobody is watching, and I don’t hug it for very long. It’s more like a lean or a quick check-in, and having touched something rooted I feel more rooted myself.

One autumn I made a trip to my friend Rachel’s cabin in Vermont, a beautiful part of the country famous for its foliage. Predictably, I loved it. There were a great number of trees to hug, and just wandering among them was a balm. Russet red and glowing gold, stretching over hills. I felt just like Diane Keaton’s character in Baby Boom, apart from the whole “inheriting a baby and sleeping with a vet” part, which sadly has yet to happen. I did make pies and tromp up a mountain and take a thousand dappled photos of the forest. On the car journey back I had the distinct feeling that I was leaving nature behind and stepping back into an artificial world. I hauled my bags of apples up the steps of my apartment building and turned to wave my friend off, and who did I see? The maple tree on my street, of course, and I could swear he was waving back at me. Pretty embarrassing for him since I was waving at Rachel, but still!

Being a grown-up isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. All the knowledge I gained made me forget that the city is nature too, and I am nature, and separations are simply illusory. Somewhere along the way I must have learned that trees are not living things to be treasured, but objects for humans to use. The term “tree hugger” is a pejorative, embedded in my brain so deeply that I can’t recall the first time I heard it.

I know what is meant when someone is called a tree hugger: it’s dismissive and ridicules the person, inferring they are an ineffectual and naïve hippie. It is supposed to mean a kind of pathetic figure with an embarrassingly emotional connection to an object. That’s incorrect, and I’ve discovered that a big part of what is missing when we talk about trees, or the ocean or the planet, is exactly that: an emotional connection. The natural world is something felt. That rare eucalyptus tree, and what it felt like to hide in the branches there, was something I felt and never quite put into words until now.

At the risk of stating the obvious: when sharing something I’ve felt, I need words. Nature is something we talk about and understand through words, especially as we get older and spend less time feeling what it’s like to be up among the trees. It is more than words we need to change; it’s actually our relationship with the planet and all the creatures and even “things” around us. Words are a good start, though, because language shapes thinking. The way we tell a story also creates the story.

Some words we have outgrown—“climate change,” for example which was deliberately conceived to desensitize people to the magnitude of the looming disaster. Some words, we are stumbling toward—“the Anthropocene,” for example, or “Martians,” as in, should we all be planning for life as one? We must search for words that are clear as a bell, that won’t seem up for debate. I’m far more comfortable in a library than in a jungle, and would rather get lost in a book. Words are my nature too, so I wrangle them in whatever way I can. It can feel hopeless to contemplate the enormity of the challenge that we are facing as we continue to destroy nature, despite relying on nature for our own survival. Something we do have control over are the words we use.

Learning how to talk about the age of extinction we are living and dying through has been a process for me. I cohosted a climate podcast for some years, and I am so grateful for what it gave me: access to lots of good information on what was happening to the climate, and also the space to figure out how to talk about it. Climate communication is political—everything we do is. Orwell wrote the following in 1946, and it’s still true today: “In our age there is no such thing as ‘keeping out of politics.’ All issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred and schizophrenia. When the general atmosphere is bad, language must suffer.”

The atmosphere is bad, and language has suffered. This is no accident. Rising temperatures and sea levels, hurricanes, floods, fires—we all know of and many of us have experienced the violence of these climate crises. To lump them all under the benign-sounding “climate change” is baffling. At least it was to me, until I learned where that modest moniker for such awful and total chaos came from. In 2002, a Republican strategist named Frank Luntz wrote a memo. Luntz is familiar to many for his association with US politics and voter focus groups. He worked for Ross Perot and Rudolph Giuliani and is credited with shifting the frame from the term “estate tax” to “death tax.” “Estate tax” sounds like it applies only to very rich people, which is and was always the case; it generally affects only the top 1 percent of taxpayers.

Switching to “death tax” sounds like everyone will have to pay, since everyone will die. Republicans were able to drive up support for repeal using this neat trick. So when I say Luntz is a “communicator,” what I mean is his entire professional purpose seems to be unmooring language from whatever unpalatable reality he is tasked with obscuring. This particular memo related to climate change and it pushed two big ideas. One was to communicate at all times that the science was not yet clear on what was causing global warming. “The scientific debate is closing [against us] but not yet closed. There is still a window of opportunity to challenge the science.”

I get so furious when I read that sentence my breath thickens. From time to time I see Frank Luntz being a talking head on cable TV, billed as a communications expert. That is exactly what he is, and maybe that’s the reason I’m more incensed by him than by the people who carried out his instructions. He understands the power of language and he used his gift with words to set this country firmly on a path of death and destruction. Many years later Luntz tried to put his filthy genie back in the bottle, but it was too late.

By 2017 the bottle was smashed to pieces when the Skirball Fire threatened Luntz’s Los Angeles home. Of course, neither he nor his house burned; in any case the wealthy are the most likely to survive climate catastrophes. The scare was enough for him to change tack and testify before the Senate’s Special Committee on the Climate Crisis that he had been wrong in 2001, saying: “Just stop using something that I wrote 18 years ago, because it’s not accurate today.”

It wasn’t accurate then either. And why would people who benefit from the confusion he sowed ever stop sowing? Another part of his 2001 recommendation was for Republicans to stop saying “global warming” and start saying “climate change.” Luntz advised, “While global warming has catastrophic connotations attached to it, climate change suggests a more controllable and less emotional challenge.” Republicans, including the then-president George W. Bush, did just that, and then some. The Guardian reported that “the phrase ‘global warming’ appeared frequently in President Bush’s speeches in 2001, but decreased to almost none during 2002, when the memo was produced.” In swapping “global warming” for “climate change,” the Bush administration helped to establish the latter as a catchall to describe something vague and broad.

“Climate change” can mean any number of things to any number of people, and this looseness has been exploited by deniers and delayers. Sanitizing the language was step one, and it was followed by decades of destructive climate policy and rising carbon emissions. This rise was met with increasing global temperatures and a growing number of climate migrants. Taking the emotion out of words necessitates taking the anger out of suffering, but for the human race to survive this will take no small degree of fierceness.

The first tree huggers were incredibly fierce. The term was coined more than two centuries ago when 294 men and 69 women of the Bishnoi sect of Hinduism physically clung to the trees in their village in order to prevent them from being used to build a palace. The story takes a gruesome turn, when these tree huggers were killed by the lumberers who cut down the trees. Can you imagine putting your body on the line for a tree? In 1974 in Uttar Pradesh, India, a group of peasant women hugged trees, using their bodies as a physical barrier to protect them from foresters. This practice spread, culminating in the Chipko (meaning “to hug”) movement, which forced deforestation reform and greatly helped to protect trees in the Himalayan region.

At my local park in Brooklyn, Prospect Park, there are three saplings, growing stronger each month. Those trees were planted to mark the spot where a man set himself on fire in April 2018. David Buckel, a civil rights lawyer turned environmentalist, self-immolated in an attempt to ring the alarm, to wake people up. “My early death by fossil fuel reflects what we are doing to ourselves,” he wrote in an email to media. “Pollution ravages our planet. Most humans on the planet now breathe air made unhealthy by fossil fuels, and many die early deaths as a result.” His email ended with, “Here is a hope that giving a life might bring some attention to the need for expanded actions.”

Today, deforestation is a leading cause of global warming. In 2010, together with agriculture, it accounted for about 24 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. A report in Scientific American states that deforestation in tropical rain forests adds more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere than the sum total of all the cars and trucks on the world’s roads.

One of the least discussed but, I suspect, most effective agents in the race to save ourselves from extinction is reconnecting to nature. When I hug a tree I geta blessed glimpse of the truth, which is that I’m a very small part of a gigantic ecosystem. David Buckel is often on my mind when I take walks in Prospect Park. He was right about man-made pollution ravaging our planet; everything he said is true. I’m not interested in derisive terms like “tree hugger” or “hippie” for people who care about the things he cared about. It’s not silly or even illogical to hug a tree, but it is pure madness to blindly continue destroying our only home. I’m regularly surprised by how enmeshed I am in the ways we wreck this world of ours. Hoping will not change what’s going to happen. I hope that Michael B. Jordan will fall in love with me and together we will move to an island and found a donkey sanctuary. But hoping won’t make that happen— action will. Until I find out where he lives and muster up the courage to propose to him, there is little chance we will even form a relationship!

Being hopeless is equally ludicrous. It is fashionable today to face doom with a nonchalant nihilism, but behaving as though the apocalypse is inevitable dismisses the hard work of many who are trying to prevent it. You must earn the right to be hopeless. Unless you have truly exhausted all of your options you can’t truthfully claim hopelessness.

In a mess this big, if you want to claim hope, the only correct course is action. That shouldn’t be so hard but, for me at least, it is. Curbing my own behavior feels almost ridiculous when I know that twenty fossil fuel companies are responsible for one-third of all carbon emissions. Knowing the political history and profitability of climate change denial, and having lived under the Trump administration for four years, which was almost laughably dedicated to endangering us all, I find it difficult to imagine I, just one person, could do anything. But it’s even more difficult to ignore my own complicity. It’s that discomfort that makes me act.

That and Sadie, my pink-cheeked niece in Ireland who looked up at me the last time I visited and said, “Sometimes I wonder, is that moon following me?” Sadie is five years old. She deserves a fair chance at a healthy and safe life, just as every child does, even if they’re not as cute as she is. We go on having children at the same time as we are wrecking their only home, which is really difficult to accept. So perhaps there needs to be a word for that, like paying it forward except you’re not doing them a favor; you’re making their lives worse. Owing it forward? Making your children pay your debts? How about “death tax”?

I did one small thing—I joined a credit union and posted a picture of my chopped-up Chase Bank cards on Instagram. Suddenly, all of my friends—and their friends—were clamoring to know how they could do the same. I broke the internet. It was exactly like the time Kim Kardashian released photos of her bare bottom except with taking constructive action to prevent total climate collapse. Everybody wanted to know how they could leave too, as if I had cracked some secret code that gave me agency over my own behavior. The thing is, I’d been meaning to leave for ages, ever since I learned about how Chase and other American banks invest their customers’ money in the fossil fuel industry. At one point I called Chase and the customer service lady hung up on me when I asked her about the bank’s deadly practices.

Buying, taking, and using exhausts me and depletes everything around me, except the companies profiting from my behavior.I wish I could have left then and there, but I wanted to pay off my credit card bill first. I owed Chase thousands of truly unnecessary dollars because my credit card had a mind of her own! She was trashy and lazy, always putting me into Lyfts instead of letting me walk or take the train. She loved nothing more than ordering food online instead of allowing me to cook, and would stay up late at night buying too many skin-care products on Amazon. The funny thing is, I never really agreed to all of that. I missed walking; walking calms me down. I like cooking, and I never worried about my skin until I started buying all those potions. It is also not lost on me that the things I spent money on—the real reasons I got stuck with Chase—took a heavy toll on other people, land, and animals.

Buying, taking, and using exhausts me and depletes everything around me, except the companies profiting from my behavior. One way to view it is that my credit card put me in a car driven by a person trying to get by in a punishing gig economy. Unlike Lyft drivers, public transport workers are unionized and paid a fair and regular wage and, of course, the carbon emissions are lower than cars. My old credit card made the food delivery app Seamless an easy choice too. But ticking the box that mockingly says, “Spare me the napkins and plasticware. I’m trying to save the earth,” made me furious.

So I cut her up and closed my account. They make it a little bit tricky, in that you have to sit in one of those fake offices in the middle of the bank with a sweaty twenty-two-year-old and tell them why you’re leaving. I was abashed, facing the young manager in his terrible suit, answering when he asked the reason why I was leaving: “Um, because Chase funds fossil fuel companies and that is . . . bad.” All my bravado had fallen away. “Okay, I’ll type that in. Okay, awesome!” he said with no hint of reflection.

He worked for a company that was deeply complicit in the injustice that is climate change, and I gave them my money for years. I felt no rancor toward him or myself, understanding that it was just a pretty stable job, just a fairly convenient bank. I didn’t feel smart or holy. I just felt lucky I had finally understood that I had some agency over small choices. I felt so light and free the day I left the bank, it was almost comical. As ever in my dark Irish brain, comedy and tragedy are forever chasing each other around in circles.

I’m not sure it’s fair, the amount of rage I feel toward Frank Luntz and other wordsmiths who pave the road toward obliteration. Is it really too much to say that words nursed this age of extinction into being? Like Frank Luntz, I’m a Republican strategist. Sorry to let you down, but how else could I afford a home in LA? I’m joking! But what I do have in common with him is that language and storytelling are also my chosen form of communication. The Luntz memo illustrates the power of language. He advised a small number of people to stop using some terms and start using others, and the future of the entire planet and everybody on it moved in one direction. If George W. Bush had not prioritized capitalism over climate justice, where would we be today?

__________________________________

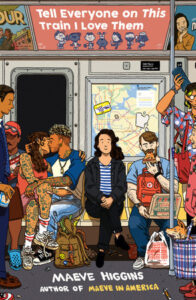

Tell Everyone on This Train I Love Them by Maeve Higgins is available via Penguin Books.