Madhushree Ghosh: How Cooking Helped Me Build a New Home

“What am I choosing to remember?”

In 2014, when my marriage and in turn, life fell apart after splitting up with my partner of 17 years, I moved back from Maryland to San Diego, where I had lived for seven years and felt was as close to home in America as I could be. That same year, I realized the biggest challenge I have is my memory: not the loss of it, but extremely vivid recollections of events, days, actions. I remember stories, episodes, and events from decades ago in clear detail. How people said what they did, what they were wearing, what I was doing, where we were.

When you’re told you have a photographic memory, you’re expected to revel in it as if it’s an advantage. It’s not. It means even when you want to forget, you cannot. Grief and the trauma of grief become part of that memory. It’s what my memory holds onto from my dead marriage and its aftermath that I’m fearful of. But then, as Joan Didion said in Blue Nights, “Memory fades, memory adjusts, memory conforms to what we think we remember.”

I have to be careful when I talk about my history and where I come from—what am I choosing to remember? This is tricky because the memory cells adhere to what they want to.

*

After Baba, my father, died in 2004, the neighbors made sure to ask my mother what happened.

“How did he look that evening?”

“Was he happy and content?”

“Then what happened that night?”

When did she, my Ma, wake up to hear Baba struggling to breathe?

“And then what happened?”

When she screamed at him saying, “Shono, ki holo? Ki holo?” and Baba raised his hand signaling, wait, wait, give me a minute, and then he fell back on the bed, what did she do?

The neighbors asked over and over, “Mrs. Ghosh, Sila di, what did you do? Did you call for help? Did you call your doctor? What did you do?”

I remember Ma responding. “‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Wait,’ he whispered, ‘daaraao, daaraao,’ and then his body hit the bed hard. He fell back on his pillow. I tried to call the next-door neighbors, but I forgot their number. I am a math teacher, numbers are what I do. That night I forgot the number. I don’t know how long I looked through the notebook to find it. I tried to wake him up till the neighbors came with the doctor, but he didn’t get up. He didn’t get up.”

I remember sitting at the dining table watching Ma in her chair repeating herself as if it were a chant that would soothe her shell-shocked mind. I remember feeling rage at the neighbors. How dare they make her go through this? Why is Ma answering them? Week after week, the neighbors came, asking the same questions. And then slowly, Ma had her routine.

I decide I will make my own Diwali. My own festival of lights.

Now when she woke up, the nurse that Didi—three years my elder, and the decision-maker between the two of us—and I employed made her toast and tea. Then, she walked up and down the hallway, lifting her arthritic feet one after another, her exercise to keep up her waning physical mobility. She showed the nurse what to cook, told the maid what to clean. She ate lunch, made calls to relatives, some friends, then napped in the afternoon. Then she ate her dinner, and the nurse helped with her medicines before tucking her in bed, pulling the heavy but warm and inviting wool lep over her bony torso. Ma’s rituals after Baba left us became routine, a habit, as if she had lived like that for years.

Soon, she didn’t talk about that night in October 2004, the last night of the Indian festival Durga Puja, when she lost her partner of nearly five decades. Instead, her conversations were about Baba doing something to irritate her or buying her the best handloom sari or a trip they took together. Her memories were happy ones.

I didn’t—and neither did Didi—relive or talk about when we got the news. Nor did we talk with each other about what happened. Ma moved on from the trauma faster than we did. It’s not that she wasn’t sad. It’s just that she used rituals and repetition to create a new normalcy in her life.

*

I am still trying to live without Baba. I’m still living in that Sunday afternoon when his neighbor called me in San Diego, saying, “Your father is dead.”

I remember I was wearing a white t-shirt and this pair of jeans with a stripe running along the front. I remember I was to go for a job interview to the Bay Area the next day. After staying in a rental cottage behind a rich couple’s mansion for two years, I finally completed the divorce process. Mediation. Failed mediations, many of them. Court appearances. New dates of appearances. Documentation. Compromises. Financial pulls and pushes. The judge asking us to move on. Two years of this. Finally, finally, my ex yields. I tell myself, this is the price of freedom—to have the luxury to start again. At 42.

I move into my house near Old Town San Diego in 2016. It is the first space that is mine, truly mine—not Ma’s, Baba’s, nor is it the Maryland house that was bought for my ex and his family. I decide I have to create events, happiness, joys, rituals, and memories here. It is up to me.

*

We Ghoshes aren’t religious, though we love traditions such as Durga Puja, the festival celebrating the goddess Durga, avatar of Sati and Kali, coming home to earth from the Himalayas where she stays with Shiva, her husband. It’s a Bengali festival, filled with seven days of food in multicolored cloth top pandals in neighborhood parks brightly lit with generator-assisted electric connections, music blaring from loudspeakers, aroti (felicitating

the goddess with dhunuchi, coconut-camphor lit lamps, dancing to the dhaak drums), new clothes, plays, and all-night jaatraas (multiact plays). Durga Puja in our South Delhi Bengali neighborhood of Chittaranjan Park, and our childhood are what my memories are made of.

But in America, no one except for Bengalis know what it is. Pujas in Delhi may have now become commercialized with fancy singers, the food stalls may be more North Indian than Bengali, but a Delhi puja isn’t what it is in America either. My sister sends me photos—her husband in a silk FabIndia kurta with jeans, she in a bright South Indian silk sari. Holding onto rituals that were part of our lives in India when we were young. It’s not the same.

Instead of Durga Puja, I settle on Diwali. The Festival of Lights. A Hindu festival, it celebrates the victory of good over evil—of Ram returning home to Ayodhya with his wife, Sita, and brother Lakshman after fourteen years of vanvaas, banishment to the forest by his father’s third and beloved wife. While exiled, Sita is kidnapped by Raavan, the king of Lanka, and a fight over the girl ensues. Using the help of a super-monkey army led by Hanuman, Ram is victorious, killing Raavan, and returns home with his wife. Good wins over evil.

There are many problematic parts to this mythological story. That Sita needed rescuing. That Raavan, an erudite man, needed to be killed. All because Ram and his brother brutally chopped off Raavan’s sister, Shoorpanakha’s ears and nose after she had lusted for Ram. (A simple “No, I’m not interested, I’m married” might have sufficed.) The violence against women in this tale isn’t lost on me.

We never celebrated Diwali for what it represented to Hindus, given Ma always asked us to question faith. But, but. Diwali, when the native people lit lamps to guide Ram back home, celebrated with fireworks and food, I’m good with that.

In 2016, when I move into my home next to Old Town, I decide I will make my own Diwali. My own festival of lights.

*

2019 November. Lucky, the young bearded Sikh owner of Carlsbad’s Punjabi Tandoor, shows up early with metal trays laden with food. While the Festival of Lights celebration is one where food is center stage in my house, it is the one time I don’t cook. I order the best desi food I can find in San Diego from Punjabi Tandoor.

Everyone is invited—the house is full. Exactly how I want it to be.

Lucky shows me what tray needs heated and when. He waves before leaving, his turban thick, the swagger of a young man. I’ve known his family for nearly two decades—they all work the register, the tandoor, or dole out food in the Styrofoam containers with a smile for lunch and dinner. I’ve watched the daughters get married, heard them welcome grandsons to the family. I guess this, too, is how one creates family. That evening I wear a sari—one of Ma’s Benarasi silks. I feel close to her when I do. Every year, every Festival of Lights, I wear a sari, and feel Ma’s presence with me.

I want this celebration to be that of life itself. A new evening of welcoming and wishing each other well. My colleagues from pharmaceutical companies, my work team, department heads. Their spouses. Their children. The barista from the café where I spent every weekend when the divorce took all joy out of me, and he made me lattes with Ganesh designs. The cotton candy girl with the pink hair, who made whiffs of fluffed sugar with organic color.

The hair stylist who held me quietly in her salon as I let myself break down with tears rolling down my face as I told her how I compiled a list of all the jewelry Ma and Baba gave me and sent it to my now ex so he could confirm I wasn’t stealing from him. My friends for decades, silent supporters of my life, my world. My neighbors. Their children. Friends of friends. Everyone I know. Everyone is invited—the house is full. Exactly how I want it to be.

The food is what it always is—chicken tikka masala, samosas, dal makhni, spinach paneer, cauliflower, raita. Standard buffet fare but made with love and extra special. Dessert is my naru, my nod to my family, and gulab jamun, large, syrupy-sweet, deep-fried paneer balls of goodness that only Punjabi Tandoor can bring me. Then we have poetry. That isn’t a Diwali norm, but in my house it is. Poetry from Tagore to Shakespeare to Warsan Shire. We all have to recite a poem, a joke, a song, something.

“Madhu, you really make us work for our food, don’t you?” they grumble good-naturedly.

But each one of them comes prepared with a poem. A crumpled piece of paper they stuffed into their kurtas before coming to my home. A note on their iPhones they read from, their faces illuminated by the light. A child reciting a poem he has memorized. A Chinese song by a singer who also is a breast cancer pharma expert. Every one of them gets a small token, a silly gift—a pen, a face mask, a snarky post-it, a coaster—things that make no sense except that it’s a gift for continuing the tradition of joy, and community in my home.

__________________________________

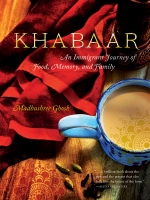

Adapted from Khabaar: An Immigrant Journey of Food, Memory, and Family by Madhushree Ghosh, published by University of Iowa Press.

Madhushree Ghosh

Madhushree Ghosh works in oncology diagnostics, and is a social justice activist. Her work has been awarded a Notable Mention in Best American Essays in Food Writing and a Pushcart Prize nomination. She lives in San Diego, California.